Declassified documents in the Israeli state archives suggest that J. Robert Oppenheimer may have played a part in not one but two nuclear projects

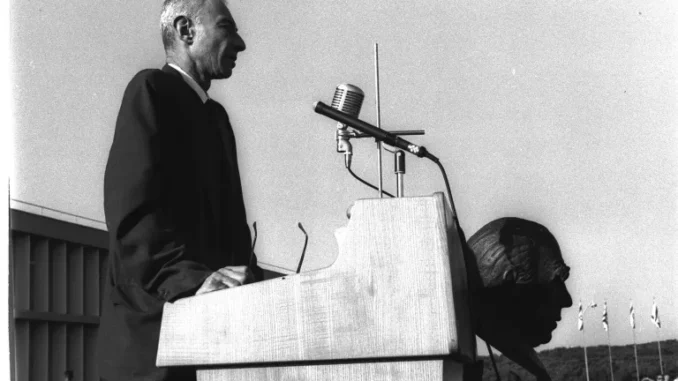

The audience at the dedication of the Nuclear Research Institute in Rehovot, 1958. J. Robert Oppenheimer, left, is seated next to Paula and David Ben-Gurion.Credit: Moshe Pridan/GPO

Pink is back in fashion this summer. While youngsters (of all ages) flocked to “Barbie” clad in her favorite color, others sought out the pink jersey of Inter Miami’s new soccer star, Lionel Messi. And then there is J. Robert Oppenheimer and the ruinous rumor that he was a pinko.

- The Jewish story behind ‘Oppenheimer,’ explained

- How Israel Built a Nuclear Program Right Under the Americans’ Noses

- How a Standoff With the U.S. Almost Blew Up Israel’s Nuclear Program

Christopher Nolan’s new movie “Oppenheimer” is an important work dealing with an important subject. Yet while it is quite good, it does not soar to masterpiece level and is disappointingly flawed in its final hour. I will not give away the entire plot, suffice to say that rather than keeping its eye on the main storyline, the film goes off on a tangent. The writer-director apparently fell in love with a certain twist and carried it forward, regardless of the deviation from the title character’s narrative.

If that is a valid criticism of the three-hour movie, one can hardly expect it to spare even a minute for more arcane details in the stormy life of the director of the 20th century’s most momentous project: the U.S. quest to build an atomic bomb in order to end World War II.

So, it is left to journalism to add to the vast Oppenheimer scholarship by delving into the Hebrew archives and declassified documents to shed light on “the father of the bomb” and Israel’s hush-hush decision in the 1950s to develop a nuclear infrastructure, potential, option – whatever one wants to call it as long as the correct term remains unmentioned.

At the time, the U.S. government did not suspect Israel of being on the path to a secret nuclear project. Harnessing atomic power for research, electricity or desalination was a perfectly innocent proposition, albeit financially doubtful.

“Israeli” as distinct from Jewish, because the role played by Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard – whose August 1939 appeal to President Franklin D. Roosevelt for America to be the first to develop “a very large bomb” helped launch the Manhattan Project – as well as Isidor Isaac Rabi, Edward Teller and Oppenheimer’s benefactor-turned-nemesis Lewis Strauss is a constant undertone in Nolan’s drama. They all strove for America and mankind, and against evil as personified by Hitler (and later Stalin), with an additional “our tribe” dimension. Israel, however, is totally absent from the film narrative.

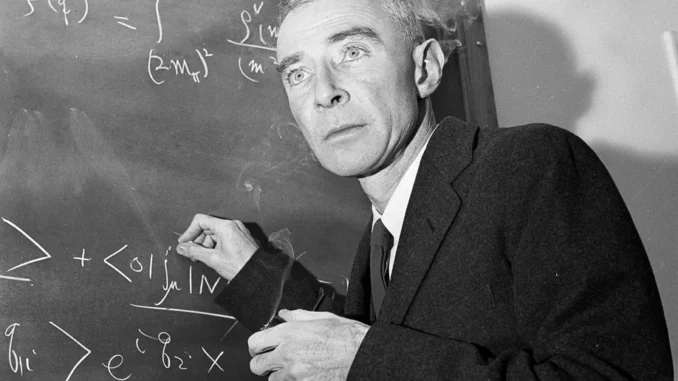

As is known, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made him world famous, Oppenheimer fell from grace when a series of charges from an earlier period were used to strip him of his top-secret security clearance. Rather than laugh it off as petty and irrelevant, continue with his scientific and public policy roles, and refer to the assault on his integrity and loyalty as just another manifestation of the McCarthyite madness sweeping America, he insisted on taking part in a proceeding that laid bare darker corners of his past: the prey came to the predators. Within the span of a few days, he fell from his pedestal and became a pariah. The fame of ’45 turned into the shame of ’54.

The secret U.S. Atomic Energy Commission hearing took place in April-May 1954 and was made public by The New York Times in mid-April. This timeline is important, because it shows how quickly the Israeli government sought to exploit that event.

This was the early atomic age in Israel. Nobody dared talk about military usages. Only the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain were members of “the nuclear club.” Even France and China were years away from having nuclear weapons. Israel had neither immediate need nor available resources for such grandiose schemes. It could barely absorb the deluge of immigrants or safeguard its own borders.

David Ben-Gurion, however, was fascinated with the idea of atomic power. Israel’s founding leader and defense minister spent 1954 on a sabbatical in the remote Negev kibbutz of Sde Boker. Back in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, officials he had appointed kept up the good work. It was a slow germination, but without it the Israeli nuclear project would have been as barren as the desert around Sde Boker.

In the office of the prime minister, which for Israel’s first two decades was mainly combined with the role of defense minister, the main actors in this endeavor were Dr. Ernst David Bergmann and Teddy Kollek. Bergmann headed both the Israel Atomic Energy Commission and the Defense Research and Design Division (a forerunner of Rafael Advanced Defense Systems). Kollek, the director general of the Prime Minister’s Office, was a one-man Mossad with impressive contacts in the U.S. intelligence community. Later on, as the nuclear enterprise in the Negev town of Dimona took shape, his counterpart in the Defense Ministry, Shimon Peres, would emerge as the political powerhouse behind the pioneering work.

Kollek’s close associate in Washington and Jerusalem was another seasoned intelligence operative, Meir “Memi” Deshalit (aka De-Shalit). His younger brother, Prof. Amos Deshalit, was one of Israel’s most gifted young scientists. He led a team of a dozen or so physicists and engineers exploring the wonders of the nuclear world at Rehovot’s Weizmann Institute of Science.

Against this backdrop, Oppenheimer-watchers pondered how to use his sudden predicament to Israel’s advantage. The close-knit atomic cadre needed to expand their knowledge and know-how: the first theoretical; the second practical. The following were much in demand: research papers, progress reports, fellowships in relevant U.S. universities, American colleagues spending their sabbaticals in Israel – whatever could enlarge the local learning pool and hopefully also provide crucial cues and shortcuts.

At the time, the U.S. government did not suspect Israel of being on the path to a secret nuclear project. Harnessing atomic power for research, electricity or desalination was a perfectly innocent proposition, albeit financially doubtful. The subject matter notwithstanding, American Jews also had to contend with suspicions of dual loyalty. Zionists helped Israel with arms, money and volunteering for combat in 1948 and beyond, under the watchful eye of the FBI. Jews were central to the Soviet-run spy rings uncovered by the U.S.’ Venona counterintelligence program.

Whether their second motherland was Russia or Israel, their coreligionists did not want to be perceived as being guilty until proven innocent. In that, they were not alone: Until JFK came along, Catholics in public affairs had to deny they would obey the Holy See. But the combination of Judaism, atoms and security, not to mention the coincidence in which the “J” in J. Robert Oppenheimer stood for Julius – as in Jewish Soviet spy Julius Rosenberg – meant that Israel had to tread very carefully in approaching Oppenheimer.

‘Can Israel benefit?’

It lost no time in doing so, though. A mere five days after the Oppenheimer scandal broke in The New York Times, Victor Salkind sprang into action.

Dr. Salkind was the Israeli science attaché in the Washington embassy headed by Abba Eban. In a long letter stamped “secret” and only much later declassified, Salkind wrote to Eban and the U.S. Affairs department in the Foreign Ministry, laying out the options and their price tags. He based his findings and recommendations on conversations with Oppenheimer, and personal and professional acquaintances.

Salkind noted that the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton – a haven set aside for Einstein (who turned down Ben-Gurion’s request to be Israel’s second president and would die a year later) and run by Oppenheimer – was mostly funded by Jewish largesse. Indeed, the original donations for the site came from the philanthropists Abraham Flexner, and Louis and Caroline Bamberger. A dozen or so of the 17 board members were Jewish, Salkind wrote.

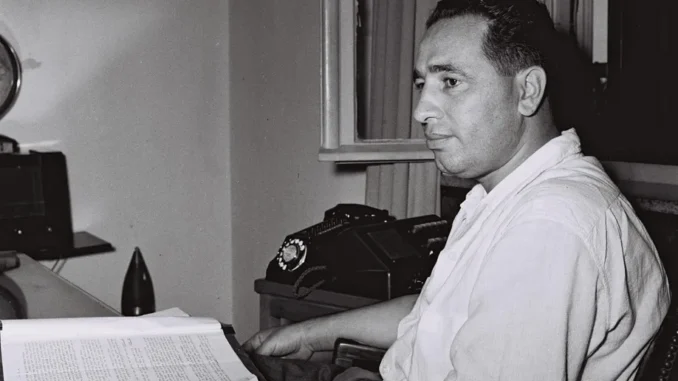

Oppenheimer is shown at his study at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1957. The institute was mostly funded by Jewish largesse.Credit: John Rooney/AP

“Can Israel benefit from the unfolding crisis? Naturally, from the first moment we thought of exploiting scientists’ resentment, hoping to talk them into making aliyah – headed by Dr. Oppenheimer – and conditioned on our ability to make sure people of Oppenheimer’s quality can pursue their studies, focusing at least on theoretical research.”

Salkind then threw cold – or was it heavy? – water on his own idea: “Unfortunately, my hopes are not high, for several reasons.”

He speculated that Oppenheimer might come out ahead after the security hearing and once again be a favorite of the Eisenhower administration, in which case the scientists would prefer to stay put. Conversely, if his tormentors won, he and the other victims would probably be denied the right to leave the United States. Too many of their colleagues had defected to the Soviet Union. For all their pronouncements of aliyah, Jewish emigration applicants would be suspected of having Moscow as their final destination.

Salkind: “We had a frank talk and he gave us important advice. We were impressed by his courage when he warned us to have no illusions regarding a ‘gentleman’s attitude’ by the Atomic Energy Commission should we come into agreement with it to look for radioactive resources in our country.”

Even if this assessment proved too pessimistic and emigration was approved, Salkind mused, Israel could end up alienating the U.S. government and, “based on unpleasant precedents,” endanger the relationship. However, he continued, Oppenheimer had definitely shown a positive view toward Israel.

In November 1952, Salkind and Memi Deshalit visited him at his Princeton office. The former revealed: “We had a frank talk and he gave us important advice. We were impressed by his courage when he warned us to have no illusions regarding a ‘gentleman’s attitude’ by the Atomic Energy Commission should we come into agreement with it to look for radioactive resources in our country. He said it to us even though he must have known that the FBI is recording his every word and submits it to his personal file.”

Salkind’s recommendation was “to express our sympathy to Dr. Oppenheimer during this difficult time he is undergoing. For now, let’s do it indirectly – we can find the right way – as a direct approach might only damage his present position.”

Memi Deshalit and the Foreign Ministry concurred with Salkind’s reasoning. Following consultations on the matter, Deshalit replied in May 1954, it was decided that the Weizmann Institute would extend an invitation to Oppenheimer to come over as a visiting professor – the same way “other great men of science have been invited.”

Meyer Weisgal, the chairman of the institute’s executive council, agreed to write the letter of invitation. It was delivered to Oppenheimer’s office by hand, bypassing the FBI’s scrutiny.

Acting at the pace of a military operation, Weisgal promised to follow up the letter with a personal visit in which Oppenheimer could respond both to the invitation and consider aliyah. This, Deshalit noted, may not have been a practical proposition, but coming as it did during Oppenheimer’s time of trouble, would “get him closer to our issues. And when he is hopefully cleared, he could help us in the future through visits, granting our scientists more access to the Princeton institute, etc.”

However, asked by Deshalit whether it had an opinion on whether Oppenheimer should be invited over for an extended period or if the invitation be made public, the embassy – in a response signed by First Secretary Esther Herlitz rather than Salkind – was unenthused. It noted that Weisgal’s letter and the interdepartmental correspondence “were read with great interest. In our view, Israel manifested a very nice gesture with Weisgal’s invitation. We find no need to add another invitation, official or otherwise. We will keep in touch with Weisgal. Should Oppenheimer accept the invitation, we are far from certain he would be allowed to leave here.”

Oppenheimer opted to stay in the groves of academe, to which he had returned from another Groves: Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, the boss of the Manhattan Project and his wartime superior.

‘Grave situation’

Some four years elapsed before Oppenheimer felt secure enough to accept a new invitation from the Weizmann Institute, as an esteemed guest at an event. By then, the Oppenheimer affair, as well as the entire discredited McCarthy period, had disappeared from the public discourse. The world had marveled at Israel’s sudden military prowess in the Sinai Campaign of 1956. The Soviets’ Sputnik satellite had ushered in the Space Age a year later. And in 1958, Israel celebrated its 10th anniversary. It was an entirely different context, and Oppenheimer would be a welcome and distinguished guest.

At the Rehovot event, he was notably seen next to David Ben-Gurion and his wife Paula, and talking with his fellow physicists. Someone who stood out was the youthful Amos Deshalit, who was secretly involved in the Dimona project.

Ben-Gurion said Oppenheimer told him he “feared for Israel’s fate because of the Russian-Egyptian relationship, especially in regard to an atomic reactor. He considers it a grave danger.”

Only 11 out of 15 ministers and a single secretary attended the next cabinet session, where Ben-Gurion – swearing them to secrecy “because of the sensitivity of the issue and the person” – shared his insights following his conversation with Oppenheimer, which had come at the latter’s request.

Ben-Gurion did not confide in Oppenheimer, however. The 1956 deal between France and Israel for a small research reactor was shrouded in secrecy. Had Oppenheimer been given an inkling, it would have put him in a bind again. Better for him to be told nothing; better for Israel too.

The strategically redacted transcript of the June 1, 1958 ministerial meeting shows Ben-Gurion being “somewhat anxious, because I’m not certain that whatever we say here will not end up in a newspaper, and we have no right to do that as the person’s position in his country is quite delicate – it’s Oppenheimer. Of course, the matter is also delicate, but I trust my colleagues to understand that it is spoken about only here.”

When they bumped into each other at the Weizmann Institute, Ben-Gurion recounted, “I had the impression, perhaps not even founded, that a Jewish spark lit in the man. Upon his expressed wish to have a chat with me, I was quite willing. He came over and we had a long talk.”

Ben-Gurion said Oppenheimer told him he “feared for Israel’s fate because of the Russian-Egyptian relationship, especially in regard to an atomic reactor. He considers it a grave danger. In political affairs, he is quite naive: he advised me go to the UN, the Security Council. He believes we should do everything in order to have an atomic power plant, soon. But regarding Russia and Egypt, it is a grave situation that makes him fear for Israel.”

The prime minister’s vision of a nuclear Israel was not based on domestic political consensus. He obviously used his references to Oppenheimer’s views, which may have been selective, to convince his audience of his own long-held opinion.

“I am not bringing up any draft decision right now,” Ben-Gurion went on, indicating that he wouldn’t raise it while Finance Minister Levi Eshkol was on sick leave. “It’s just that even before the conversation with Oppenheimer, this was a constant nightmare for me. But especially after this talk, it bothers me.”

Quoting Proverbs 12:25, he told the ministers: “I said, ‘Care in the heart of a man boweth it down.’ We won’t decide anything today. It’s a budgetary matter.”

As for the rest of his conversation with Oppenheimer, Ben-Gurion recounted their arguments regarding a nuclear World War III. In Ben-Gurion’s opinion, the Russians would not risk such a war because they believed they would win a conventional one anyway. He said Oppenheimer agreed, “but with one caveat: that there is no defense against the atomic and hydrogen bombs. Perhaps there is such a system that can sense the bomb and then send the system against the bomb or the missile and set it off. He does not know whether the Russians have it, but he is not confident they won’t – and then they could start a war.”

Hearing Oppenheimer’s views made Ben-Gurion “extra-worried. I was worried before, but to hear it from this man…”

However, one minister, Zalman Aran, remained skeptical. He wondered whether Oppenheimer based his views on facts or just assumptions, because “if this is just what he thinks, well, I could have thought about it myself.”

Ben-Gurion did not miss a beat. “Indeed, I did think about it myself, but he knows the subject matter while I am but a layman.”

If Oppenheimer’s views, as told to and by Ben-Gurion, played any part in the Dimona decisions, then the Jewish physicist who helped change the world influenced not one but two nuclear projects.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.