By Jon D. Levenson, JEWISH REVIEW BOOKS

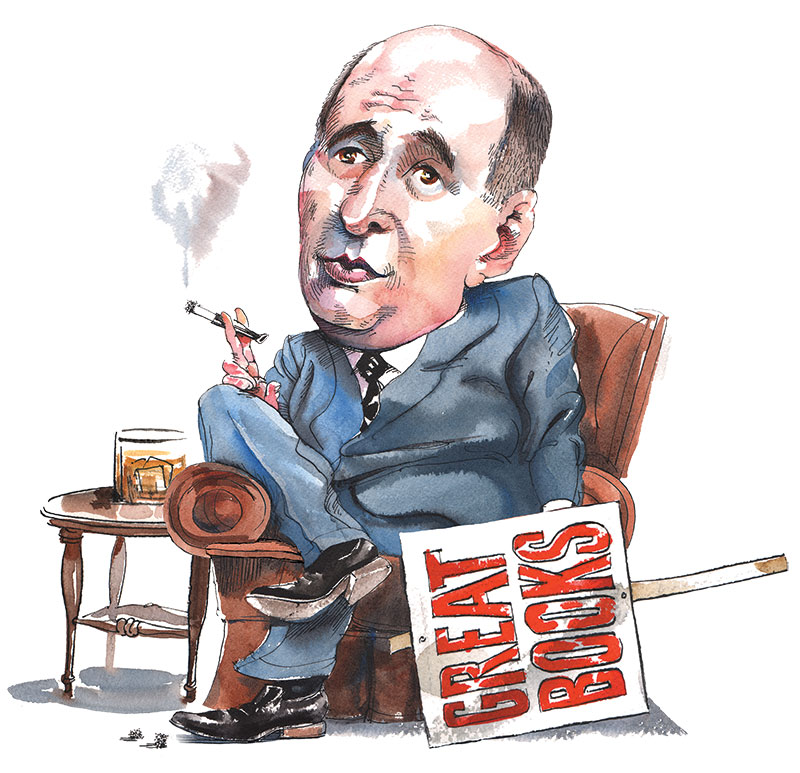

Allan Bloom. (Illustration by Mark Anderson.)

Watch Allan Bloom in a 1987 interview.

Thirty years ago, a book was published that hit, in the words of its New York Times review, “with the approximate force and effect of what electric shock-therapy must be like.” A professor at the University of Chicago, previously known to those outside that institution principally for an annotated translation of Plato’s Republic, suddenly found himself the author of the top-selling work of non-fiction in the country—and the center of a firestorm of public controversy of a sort rarely seen among scholars of the humanities.

Werner Dannhauser, in an appreciative survey, listed fully 16 charges that reviewers leveled against Allan Bloom and his The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students: idealism, sexism, racism, elitism, Straussianism, esoteric writing, sloppy writing, absolutism, making scapegoats of students, ignorance of professional philosophy, un-Americanism, failure to understand rock music, pessimism, uncritical advocacy of the Great Books, bad scholarship, and neglect of religion. In a particularly scathing (and influential) review, Martha Nussbaum added another, that Bloom ignored Greco-Roman texts that contradicted his vision of the classical past, but it was the alleged elitism of his vision that Nussbaum hit the hardest. Bloom was, she charged, “really proposing that the function of the entire American university system should be to perfect and then protect a few contemplative souls, whose main subject matter will, apparently, be the superiority of their own contemplative life to the moral and political life.”

Ironically, however much the credentialed professoriate panned The Closing of the American Mind for its putative narrowness, the broader public found something of great value in it. At one point, Simon & Schuster was printing 25,000 copies a week—no doubt a record for a book that dealt with such difficult figures as Plato, Aristotle, Nietzsche, and Weber and that was itself far from an easy reading experience. The discrepancy between the difficulty of Bloom’s book and its popularity became a topic of discussion in its own right. Dannhauser, a friend and former colleague of Bloom’s, speculated that the sales were owing to the unease parents had felt with the education for which they were paying. Such parents “had watched their children go off to get a liberal education,” he wrote, “and come back with all sorts of substitutes or by-products: addictions, neuroses, unearned cynicism, a sense of emptiness.”

As bad as the situation was that Dannhauser described on campus some three decades ago, things have deteriorated markedly. Most newsworthy have been the recent incidents of violence against speakers who dare to challenge one or another reigning orthodoxy of the academy. Less noticed, but arguably more troubling, is the self-censorship on the part of faculty and students who are not inclined to face the shunning, or ersatz judicial procedures, that voicing their dissent, or even sketching out an alternative, might provoke. My sense is that at most elite institutions today, those professing convictions on liberal arts education that are anything remotely like Allan Bloom’s could never get hired.

The particular issues that provoke the harshest responses are well known. They tend to center on questions of race, gender, sexuality, and, perhaps incongruously, Israel. Whatever the conceptual difference between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, the condemnation of Israel shades easily into contempt for all things Jewish, and Jewish students, especially those willing to identify as pro-Israel, have been made to feel unwelcome on some campuses. A similar distaste for committed Christians, especially those who articulate dissent on the regnant sexual ethic, is also evident. As William Deresiewicz, a scholar of English literature and a vocal critic of the culture on elite campuses, has recently written, “There is always something new, as my students understood, that you aren’t supposed to say,” and, as a result, not only students but also “many faculty members . . . are teaching with their tails between their legs. They, too, are being silenced.” The change is striking and raises an intriguing question: Why has modern academic culture proven so vulnerable to the forces now transforming it so fundamentally?

Were Bloom alive to see this situation, I suspect he would say that it is the predictable consequence of the issues he described in 1987. There would be some truth in this claim, but there are also important aspects of the current situation (and even the situation in those days) that, in my judgment, run counter to his analysis and call it into question. To sort this out, we must first examine his interpretation of academic life as it stood when he wrote The Closing of the American Mind.

Bloom’s central claim was that the university, its curriculum, its professors, and—most importantly to him—its students suffered first and foremost from the lack of any conception of truth and were thus enmeshed in a deep and self-destructive cultural relativism that was, in fact, destroying the possibility of a credible education. “The danger [the students] have been taught to fear from absolutism is not error,” he wrote on his first page, “but intolerance.” Lest one praise this stance as one of openness—a trait much celebrated in academic circles (at least verbally) then and now—Bloom observed that the term has undergone a drastic redefinition: “Openness used to be the virtue that permitted us to seek the good by using reason. It now means accepting everything and denying reason’s power.” With what sort of intellectual life does this leave us? Speaking of a former colleague at Cornell, Bloom wrote, “He said that it was his function to get rid of prejudices in his students. He knocked them down like tenpins. I began to wonder what he replaced those prejudices with.” Identifying a position as biased is easy enough; the hard part is identifying the larger and encompassing truth that reveals it as a bias in the first place and not merely as a valid alternative.

Without that truth, or at least the conviction that it exists and the passion to search for it, the university has become incoherent, a welter of “competing and contradictory” departments. “The problem of the whole is urgently indicated by the very existence of the specialties,” Bloom observed, “but it is never systematically posed.” An individual professor or student may thus believe that this or that discipline is more important than another, but the reigning relativism of the academy degrades those judgments into merely idiosyncratic preferences. As a result, Bloom writes in one of his memorable epigrammatic flourishes, “the student must navigate among a collection of carnival barkers, each trying to lure him into a particular sideshow.” No wonder four years of such an education left students feeling empty, as Dannhauser had observed.

In the especially controversial and oft-disputed second part of The Closing of the American Mind, Bloom traced the origins of this predicament to a set of German thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who, rejecting ancient claims about natural law and divine revelation alike, asserted “the radical subjectivity of all belief about good and evil.” Now, instead of morality and commandment, we hear of “values,” which are barely distinguishable, if at all, from mere preferences. Unlike truth in the older model and in the educational institutions of yesteryear, “values are not discovered by reason, and it is fruitless to seek them, to find the truth or the good life.” Worse still, such values rather easily came to be seen as human creations with an unfortunate result:

Producing values and believing in them are acts of the will. Lack of will, not lack of understanding, becomes the crucial defect. Commitment is the moral virtue because it indicates the seriousness of the agent. Commitment is the equivalent of faith when the living God has been supplanted by self-provided values. It is Pascal’s wager, no longer on God’s existence but on one’s capacity to believe in oneself and the goals one has set for oneself. Commitment values the values and makes them valuable. Not love of truth but intellectual honesty characterizes the proper state of mind.

As distant from the American university scene as the German figures on whom Bloom concentrates (mostly Nietzsche, Weber, and Heidegger) may appear, he claimed to find a direct line between their thought and popular culture in the United States. “Who in 1920 would have believed,” he asked, “that Max Weber’s technical sociological terminology would someday be the everyday language of the United States . . . ? The self-understanding of hippies, yippies, yuppies, panthers, prelates and presidents has unconsciously been formed by German thought of a half-century earlier . . . and the new American life-style has become a Disneyland version of the Weimar Republic for the whole family.”

The effects of this transformation on academic life had, in Bloom’s opinion, been devastating, leaving universities incoherent and the students purposeless. The policy of value-neutrality and its curricular consequences—the substitution of the study of history, society, and culture for the pursuit of truth and wisdom—had raised enormous problems for the life of the mind. Without something transcendent to which to commit oneself, one’s commitments themselves inevitably pale and become shallow: “When one hears men and women proclaiming that they must preserve their culture, one cannot help wondering whether this artificial notion can really take the place of the God and country for which they once would have been willing to die.” To be sure, Bloom did not advocate a return to the old beliefs about God or country, as we shall see, and only with considerable qualification could he be called a conservative.

Rather, following his teacher Leo Strauss, Bloom was convinced that the new thinking fails to reckon with the unavoidable costs of abandoning traditional convictions. Whereas “Nietzsche replaces easygoing or self-satisfied atheism with agonized atheism, suffering its consequences,” today’s students are quite free of existential agony and its attendant suffering—but only because, as the subtitle of the book suggests, their education has left their souls impoverished. However high their SAT scores, they lack the psychic energy, the erotic longing, to seek after the highest truths. (Revealingly, Bloom’s original title was Souls Without Longing.)

And there is a still-darker side to the process. For, as Bloom saw it, without a longing for the truth that transcends society, genuinely calls parochial loyalties into account, and interrogates personal commitments, what awaits us is some version of authoritarianism. The “Disneyland version of the Weimar Republic for the whole family” may seem innocent enough—until, that is, we remember what succeeded Weimar. In this light, it is hard not to think of the vilification of Israel and Zionism now found on many campuses as an omen—one that should be of concern to more than just the Jewish community.

So, what was Bloom’s remedy? First, the university must overcome the temptation to be socially and politically relevant, a temptation that is especially powerful in democracies. Instead, the university must strive to “provide the atmosphere where the moral and physical superiority of the dominant will not intimidate philosophic doubt,” cultivating therefore true “freedom of the mind,” which entails,

importantly, not only “the absence of legal constraints but the presence of alternative thoughts.” And since “flattery of the people and incapacity to resist public opinion are the democratic vices,” in a democracy the academy must fill the role once played by those aristocrats who offered ballast against the pressures of the masses. Otherwise, “there is no protection for the opponents of the governing principles as well as no respectability for them,” and when that situation obtains, what Bloom called “the theoretical life”—the unending quest to move beyond opinion toward genuine knowledge—is gravely imperiled. Ironically, to revert again to Bloom’s subtitle, higher education had in his view not only impoverished the souls of today’s students; it had also failed democracy. If his view is right, then the relationship of “elitism” to rule by the people is something very different from the stark opposition that so many of his critics instinctively assume.

Second, the current situation could not be corrected, Bloom claimed, until colleges and universities reclaimed the works of literature that once underlay the classical liberal arts curriculum:

Of course, the only serious solution is the one that is almost universally rejected: the good old Great Books approach, in which a liberal education means reading certain generally recognized classic texts, just reading them, letting them dictate what the questions are and the method of approaching them—not forcing them into categories we make up, not treating them as historical products, but trying to read them as their authors wished them to be read.

Against those who treat Aristotle’s Ethics as a discussion not about “what a good man is but [about] what the Greeks thought about morality,” for example, he pointedly asked, “But who really cares very much about that?” His answer was, “Not any normal person who wants to lead a serious life.” In sum, the Great Books are great not because they reflect a culture and a society—every book does that—but because they communicate a precious message that transcends cultures and societies and can, in the hands of the right teacher in the right institution, speak profoundly to the perennial problems of being human.

Among the Great Books, “the Bible” is mentioned a number of times in The Closing of the American Mind, although Bloom never felt any need to specify the canonical contours of the scriptures he had in mind. Rather, the Bible, or, more precisely, the loss of it as an effective cultural force, served as an object lesson on the decline of American culture. “As the respect for the Sacred—the latest fad—has soared,” he lamented, “real religion and knowledge of the Bible have diminished to the vanishing point.” Whereas in the America of not so long ago, “passages from the Psalms and the Gospels echoed in children’s heads,” now “the very idea of such a total book and the possibility and necessity of world-explanation is disappearing,” and this, too, has impoverished the souls of today’s students:

I am not saying anything so trite as that life is fuller when people have myths to live by. I mean rather that a life based on the Book is closer to the truth, that it provides the material for deeper research in and access to the real nature of things. . . . The Bible is not the only means to furnish a mind, but without a book of similar gravity, read with the gravity of the potential believer, it will remain unfinished.

In fact, in the first sentence of his chapter entitled simply “Books,” Bloom confessed that he had “begun to wonder whether the experience of the greatest texts from early childhood is not a prerequisite for a concern throughout life for them and for lesser but important literature.” Asked about his personal beliefs in an interview with Time magazine, he acknowledged the specific text that influenced his own childhood:

I’m not going to go into personal confessions. I was raised as a Jew. I read the Bible. I was taught the Ten Commandments and other laws. There were demands made of me, and I questioned them. I still question them, all the time, in every book I read. Whether there is or is not a God is still among the most critical questions in life.

And in an exceptionally moving passage in The Closing of the American Mind, Bloom attributed to the Bible—here unquestionably referring to the Jewish version—a capacity to transcend social and economic class and to generate a common culture:

My grandparents were ignorant people by our standards, and my grandfather held only lowly jobs. But their home was spiritually rich because all the things done in it, not only what was specifically ritual, found their origin in the Bible’s commandments, and their explanation in the Bible’s stories and the commentaries on them, and had their imaginative counterparts in the deeds of the myriad of exemplary heroes. . . . This is what a community and a history mean, a common experience inviting high and low into a single body of belief.

Yet precisely here we encounter a set of contradictions that calls the efficacy of Bloom’s Great Books project into doubt.

Surely the spiritual richness of his grandparents’ home did not come from anything like Bloom’s depiction of the ideal encounter with the Great Books—one in which the student is “just reading them.” Rather, by his own account, it came more from practice than from study, from observing those commandments that he continually questioned, and from creating a mode of life and not just of thought. His grandparents’ highest pursuit was thus something very different from Bloom’s own ideal of “the theoretical life.” Nor is it likely that his grandparents read the scriptures “as their authors wished them to be read.” For just as these humble Jews had no effective access to historical criticism, which seeks to reconstruct the origins of the compositions without which the intentions of the authors cannot be recovered, it is also unlikely that the Jewish commentaries Bloom mentioned were those committed to the plain sense of the biblical texts apart from what the rabbinic tradition had made of them. Rather, the practices and virtues that characterized Bloom’s grandparents’ home derived only very indirectly from the Bible; they were mediated by centuries of Oral Torah and folk tradition.

Whatever Martha Nussbaum may have meant when she observed that “Bloom presents himself to us as a profoundly religious man,” the religion in question, centered on reading classic texts “as their authors wished them to be read,” did not look much like Judaism, or any other historical religion.

A few pages from the end of his book, Bloom complicated the matter still further by acknowledging problems in including the Bible within the humanities in the first place. “A teacher who treated the Bible naively, taking it at its word, or Word,” he wrote, “would be accused of scientific incompetence and lack of sophistication. . . . Here one sees the traces of the Enlightenment’s political project, which wanted precisely to render the Bible, and other old books, undangerous.” But imagine teachers in non-religious colleges and universities who did take the Bible as “the Word.” Which would they favor, the Jewish or the Christian canon, and why? If the Christian, which would they choose, the Protestant, the Roman Catholic, or one of the Orthodox canons, and why? Would they treat the characteristic interpretations of the rejected traditions with respect or as self-evidently wrong—or not at all?

Even to ask those questions is to suggest that there is something very different about the Bible. At the epicenter of that difference lies what Jews tend to call “chosenness” and Christians “election.” Although the Bible, in all of its canonical forms, speaks of what Bloom calls “the nature of things” and of universal humanity, it mostly concentrates on something very different: the self-disclosure of God to a special community to whom he is thought to have made a continuing commitment. The “common experience inviting high and low into a single body of belief” that Bloom found in his grandparents’ home, it turns out, is common to the heirs of one of those particularistic communities but not to humanity in general; it is not universal. To assume such experience in the classroom of the culturally pluralistic college or university would be grossly unrealistic.

Moreover, if the biblical books are read in the modern educational context as Bloom recommended, “with the gravity of the potential believer,” they will not be presented “as their authors wished them to be read” at all: They will be read through the interpretive lenses of the ongoing traditions to which the believers are committed and, in some cases (certainly the Jewish), in tandem with other books with authoritative status in those same traditions. Finally, despite Bloom’s dismissal of the “Enlightenment’s political project,” if he really thought “philosophical doubt” was essential to education, then how could he banish the challenge to all systems of traditional interpretation that comes from the astonishing recovery of the ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman worlds over the last few centuries? For surely any instructor who banished the challenges that have emerged after the Enlightenment would be vulnerable to accusations not only of naiveté but of parochialism and obscurantism as well.

Bloom’s focus on “the potential believer” reflected the cognitivist or contemplative bent of his whole project. But in the case of the Bible—again under whatever definition but especially in the Jewish case—the objective is not belief alone but practice as well, observance, that is, of the norms that the scriptures disclose and the tradition interprets. One thinks of the famous talmudic dictum that study is greater than action—because study leads to action. If that is so, Bloom’s Bible reader, who approaches it “with the gravity of the potential believer,” fails, ironically, to take belief with the requisite gravity. To such a person, reading the scriptures has become an end in itself, and in that, he is far from reading them “as their authors wished them to be read.” For this kind of literature presupposes not a solitary reader contemplating the great truths and living the “theoretical life,” but rather a community of readers whose common experience derives from specific, distinctive, and identity-conferring practices. The reading and the practice enrich each other; neither is complete by itself.

Although the Bible presents an especially pointed example of the importance of practice, the principle applies, in fact, to much non-scriptural literature as well. In Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault, the renowned historian of philosophy Pierre Hadot argued that “contemporary historians of ancient thought have, as a general rule, remained prisoners of the old, purely theoretical conception of philosophy.” What they urgently need is to recognize instead that “the philosophical act is not situated merely on the cognitive level, but on that of the self and of being.” This does not mean that such works cannot be brought into the classroom of the modern pluralistic college or university, where “spiritual exercises” are thought to be a strictly private and optional matter. It does mean, however, that the relationship of the two communities of interpretation—the one committed to study and practice and regard for the authority of a community and its traditions and the other committed to a pursuit of the theoretical life without expectations of practice—is more complicated than Bloom understood.

What Bloom failed to appreciate is that when classical works of literature, especially those that are philosophical or scriptural in character, are extracted from the thick culture of practice and interpretation in which they originate and transplanted into the modern pluralistic university, they are willy-nilly transformed into something very different, losing, importantly, their intrinsic connection to what Hadot called “spiritual exercises.” If so, then perhaps the underlying assumptions of liberal arts education in Bloom’s preferred mode have, ironically, played a role of their own in setting the stage for the turbulent transformation of campus life of recent years.

Thirty years after Allan Bloom published The Closing of the American Mind, higher education in the mode he advocated is far weaker than in his day. Enrollments in humanities courses have shrunk markedly for several reasons, not all of them owing to the dominant culture of political correctness. But, as one would expect in that environment, it is not unusual for the focus now to fall reductively on the racial, sexual, or other identities of the authors read, and there is room to suspect that this change, together with the widespread penchant for theory and for jargon among humanities instructors, plays a role in the steep decline in enrollments. The claim that literature, philosophy, art, and sometimes even science function primarily as modes of social control is often assumed to one degree or another, though less often defended. But precisely because of the dominance of this ideology and the correlative silencing or even criminalization of dissent, the atmosphere in most colleges and universities is today anything but that of the easy-going relativism and tolerance that Bloom described at the opening of his book.

To be sure, Bloom would almost certainly say that the course of American academic life has followed the German trajectory from Weber through Weimar to the Nazi period, typified for him by the philosopher Martin Heidegger’s philosophical wager on Hitler. “But the Weimar Republic, so attractive in its left-wing version to Americans,” he wrote, “also contained intelligent persons who were attracted, at least in the beginning, to fascism, for reasons very like those motivating the Left ideologues, reflections on autonomy and value creation.”

To me, though, it seems that today’s campus radicals speak far less in the language of “autonomy and value creation” and far more in that of self-evident truths from which no one could ever dissent in good faith and with innocent motivation. (Having been in college during the uprisings of the late 1960s, I found this true of the more extreme radicals of that era as well.) I also have the sense that the language of “values” has declined markedly in academic life. Rather, values are often seen as mere instruments of self-interest in a fashion reminiscent of Marxist thought, except that now race, gender, and sexuality generally trump class as the key identifiers. Of course, the trajectory that Bloom traced involved massive shifts as well—Max Weber was miles from a Nazi—but today’s radicals seem to me to hold to a concept of truth (whether they use the word or not) in ways that are quite different from the thinking of the figures on whom Bloom concentrates, at least as he interprets them. How many of today’s campus radicals would ever say that “not love of truth but intellectual honesty characterizes the proper state of mind”? And how many would refrain from driving a speaker off campus if they were reassured that however objectionable his (or her) views, they were expressed honestly and with commitment?

To some of its critics, the contemporary college or university is a hotbed not of relativism, as Bloom thought (correctly or not) to be the case in his day, but rather of something closer to religion. “Selective private colleges have become religious schools,” Deresiewicz writes. “They possess a dogma, unwritten but understood by all: a set of ‘correct’ opinions and beliefs, or at best, a narrow range within which disagreement is permitted. . . . The assumption, on elite college campuses,” he goes on, “is that we are already in full possession of the moral truth. This is a religious attitude. It is certainly not a scholarly or intellectual attitude.”

A stark opposition of “religious” to “scholarly or intellectual,” however, describes religion at its worst, or nearly so—a situation in whichit has, truth to tell, often been found. In their better moments, however, religions seek to hear the best case the opposing camp can make, as in the give and take of talmudic argumentation or in the willingness by many modern religious communities to face the results of rigorous historical investigation honestly and to adjust accordingly. An analogous openness and acknowledgment of fallibility can be found in modern interreligious dialogue of the sort in which the participants strive to overcome misunderstandings and prejudices without reducing their traditions to the lowest common denominator.

Similarly, the claim that “we are already in full possession of the moral truth” contradicts a key element—dogma, if you will—of many and, mutatis mutandis, perhaps all religious traditions: that God’s mind is infinite, whereas ours is finite, and that the truth is therefore larger than even a lifetime of study and experience can ever approximate. The humility of those who have internalized that message, the saintly individuals celebrated in various religious traditions, is diametrically opposed to the smug certainty and self-righteousness that Deresiewicz finds on campuses. Finally, the ancient and widespread religious conviction that the misguided and the wicked, including one’s enemies, are children of God, possessed of a God-given soul, and thus deserving of respect or even love—this, too, strikes me as light years away from the regnant assumptions of campus radicals (and their administrative and faculty facilitators) in elite and many non-elite educational institutions today.

For Deresiewicz, as for many others, the answer to the rigidity and absolutism on campus is clear and readily available. “It’s called the First Amendment,” he writes, “and First Amendment jurisprudence doesn’t recognize ‘offensive’ speech or even hate speech as categories subject to legitimate restriction.” Therefore, he concludes, the First Amendment should be “the guiding principle at private colleges and universities (at least the ones that profess to be secular), just as it is, perforce, at public institutions.” Here we see an echo of Bloom’s stress on the “freedom of the mind,” which, as we saw, requires not only “the absence of legal constraints but the presence of alternative thoughts.” Now, if the issue is one of speaking on campus, this makes eminent sense. The educational enterprise can gain only by ensuring that faculty and outside speakers with controversial views are not assaulted or otherwise prevented from expressing themselves, as has too often been the case of late. When the focus shifts to the issues closest to the core mission of the institution, however, and the question thus becomes one of whom to hire, promote, tenure, and publish, the matter is more complicated, and here Bloom’s concern for the coherence of the curriculum and its relationship to the truth stands in tension with his own unqualified endorsement of intellectual freedom. Should universities hire, promote, tenure, and publish the Holocaust denier, the white supremacist, and the scientific creationist? A positive answer to the question is defensible only to the extent that the positions at issue are deemed sufficiently plausible as to warrant genuine consideration. No one should want falsehood to be taught or disseminated. Certainly Bloom, with his grave warnings about “accepting everything and denying reason’s power,” would have to agree.

The implication is far-reaching. Truth is not only the goal of academic inquiry; it is also the control on it. No educational institution—secular or religious, public or private—can accommodate all positions or systems of thought, as if everything were true, nor should it aspire to. As Bloom put it, “with great openness it is hard to avoid decomposition.” To thrive, especially in the modern world, institutions of learning must maintain a balance of affirmation and challenge. Without the affirmation, it will be impossible to determine which challenges must be faced and which excluded (though the judgment to include or exclude can be revised), and the “decomposition” of which Bloom warned will be abundantly evident. Without the challenge, the affirmation stagnates, loses a sense of its own contours, and, depriving itself of worthy debating partners, degenerates into either apathy or fanaticism.

At a more practical level, the greater the openness in the sense of curricular inclusiveness, the less chance there is of attaining depth in any one subject. Resources are always finite, and hard choices are always necessary. In the context of the liberal arts, one would hope that the criteria for the choices made would amount to more than just what will generate the most wealth for the student, enrollments for the instructor, or prestige and funds for the institution, or what will appease the interest group that is most militant at the moment. But in the absence of a well-articulated, comprehensive vision of the liberal arts that commands broad support from the faculties, and is pursued actively and explicitly, these more practical and less noble concerns will continue to win the day.

It is into the vacuum created by the near disappearance of an encompassing educational vision that the current political correctness on campus has rushed with such fury, providing something like what Deresiewicz calls “a religious attitude,” though of a very low order. That this attitude is taken up by students whose souls long for something that the university is not giving them is central to our predicament.

Given the social and cultural divisions characteristic of modern pluralistic societies, it is hard to imagine how an educational vision of the comprehensive premodern sort could ever be restored on most campuses. The Closing of the American Mind helped to clarify the problem, but it provides less help in pointing a way forward.

“and First Amendment jurisprudence doesn’t recognize ‘offensive’ speech or even hate speech as categories subject to legitimate restriction.”

Just because something is not forbidden, doesn’t make it permitted or desirable. No society can make laws on its members’ every move, word, or thought. There are rules in any society which regulate offensive speech or hate speech (among sane people, anyway).

Sartre wrote, for example, that antisemitism is not expression, it is passion, i.e., it is not rational.

Not even animals have the freedom of passion for the simple reason that they would never cease fighting among themselves and wouldn’t be able to survive.

Freedom of thought is also not the same as freedom of speech or freedom of expression.

Universities are (or should be) bastions of RATIONAL thought, therefore, there should be no problems with denying the flat earth society members, etc., university positions in lecturing or teaching.

The place for teaching religion is in the institutions created for that purpose. Universities can teach ABOUT religion as part of cultural anthropology or history but cannot teach religion as such.

I believe that the Great Books idea (if Bloom meant by this the teaching of the classics as has been understood for centuries) was meant to continue the tradition of freedom and civilization, of course, in addition to separately taught religious teachings (by the proper institutions).

When these things are no longer commonly and widely taught, the Western (especially) civilization will find itself at sea without a rudder, and won’t be able to recognize when it is being led from Weimar Republic to Hitlerism.