How antisemitism in Britain is rooted in the Second World War

By Martin Plaut, The Times, 23/08/2018

“From the beginning of the war there had been a considerable increase in antisemitic feeling. [Officials] seemed to regard it as quite beyond argument that the increase of antisemitic feeling was caused by serious errors of conduct on the part of Jews.”

Archive papers released to The Times show that Churchill’s bastion of propaganda and censorship allowed prejudice towards Jews to grow relentlessly. Dominic Kennedy reports

Sir Oswald Mosley leading his British Union of FascistsThomson Newspapers

That enduring motto of British stoicism, “Keep calm and carry on”, was coined by Winston Churchill’s Ministry of Information.

The morale-boosting message has been revived on mugs, posters and tea towels as a cheerfully ironic invocation of the wartime spirit that defeated the Nazis.

Yet archive papers released to The Times show that Churchill’s bastion of propaganda and censorship harboured one of the most disturbing secrets of the Second World War: throughout the struggle against Hitler, British prejudice towards Jews grew relentlessly.

Life in Britain for Jewish people during the Second World War

The discovery will revive nagging doubts about whether, had the Nazis invaded, Britons would have betrayed or rescued their Jewish neighbours.

A long withheld file, called Antisemitism in Great Britainand disclosed by the National Archives, shows that officials confronted by reports of rising prejudice decided that Jews themselves were to blame.

Chapter one: “A considerable increase in antisemitic feeling”

The ultimate consequences of antisemitism on the continent were revealed as British soldiers liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration campGetty Images

On May 26, 1943, Cyril Radcliffe, the ministry’s director-general, gathered his regional information officers to brief him. Mr Radcliffe wrote to his minister that the only regions untroubled by antisemitism were northeastern England and Northern Ireland.

“All the others showed general agreement on the fact that from the beginning of the war there had been a considerable increase in antisemitic feeling,” Mr Radcliffe wrote. “They seemed to regard it as quite beyond argument that the increase of antisemitic feeling was caused by serious errors of conduct on the part of Jews . . .

“This view held true both of officers dealing with industrial centres and those dealing with rural areas; it held true of officers coming from old-established Jewish centres, such as Manchester and Leeds, and officers coming from areas which had known the Jews mainly as war-time evacuees from the cities.

Cyril Radcliffe memo to the Minister of InformationNational Archives“

The main heads of complaint against them were undoubtedly an inordinate attention to the possibilities of the ‘black market’ and a lack of pleasant standards of conduct as evacuees.

“I reminded them that it was part of the tragedy of the Jewish position that their peculiar qualities that one could well admire in easier times of peace, such as their commercial initiative and drive and their determination to preserve themselves as an independent community in the midst of the nations they lived in, were just the things that told against them in wartime when a nation dislikes the struggle for individual advantages and feels the need for homogeneity above everything else.

“I thought that our main contribution from headquarters would be to try to keep before people’s minds the recollection that antisemitism was peculiarly the badge of the Nazi.”

The tensions around evacuation have long been forgotten but they were noted by Tony Kushner, professor of Jewish/non-Jewish relations at the University of Southampton, in his 1989 study The Persistence of Prejudice. His book estimated that about half those fleeing the East End of London were Jews. Among prejudiced comments from provincials were that Jewish evacuees had “extraordinary bad manners — noisy, aggressive, loud and tactless”.

Women and children taking cover in Bethnal Green air raid shelter, scene of the war’s worst civilian tragedyRex Features

The worst civilian disaster of the war unleashed a wave of antisemitism. In March 1943, 173 people were killed in a stampede at the Bethnal Green bomb shelter in east London. The public blamed panicking Jews, although when the bodies were identified only five Jewish people were among the victims. An inquiry found the slur to be baseless.

The conclusion of Cyril Radcliffe’s memo to the Minister of Information National ArchivesMr Radcliffe wrote: “If specific stories hostile to the Jews could be traced and pinned down as untruths, such as the recent canard of the Jews being responsible for the London shelter disaster, this should be done by countering it with the individuals who were putting it about, not by giving it general publicity.”

After the war, Mr Radcliffe drew the “bloody line” that partitioned India from Pakistan. He was knighted and became a law lord.

As Mr Radcliffe’s minute was being typed, in Amsterdam the Nazis began to round up Jews for the death camps. Anne Frank, still 13 and hiding in the secret annexe of a warehouse, was recording in her diary how, despite the hot weather, the family needed to light a fire each day to burn vegetable peelings. Any rubbish thrown into bins might arouse suspicions. “One small act of carelessness and we’re done for!” she wrote. She died in Bergen-Belsen before the camp was liberated by the British.

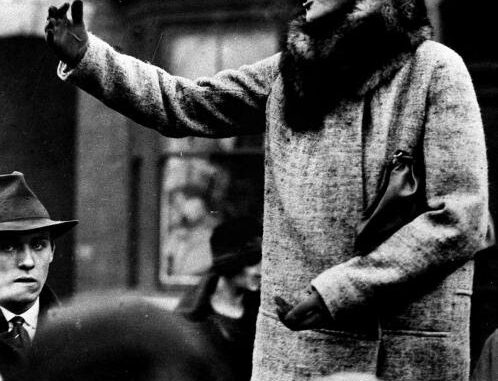

Alec Guinness in make-up as Fagin for the post-war Oliver Twist movie, which provoked demonstrations in Berlin Rex Features

The depths of the horrors uncovered by the liberators transformed the public’s view of the enemy. The historian Antoine Capet has written of “the peculiar atmosphere of the summer and autumn of 1945, when ‘the Nazi camps’ provided a ready-made ex post facto justification for the war in Britain”.

Antisemitism became taboo. In the post-war movie Oliver Twist, Alec Guinness as Fagin was made up faithfully to replicate the caricature by the illustrator George Cruikshank in the original 1838 Charles Dickens novel, complete with long hooked nose and beard. Outrage ensued. The film was banned in Berlin following demonstrations. Hollywood was so offended that the release was delayed for three years in the United States; eventually only a heavily censored version was shown.

Prejudice against Jews on the home front was quietly forgotten and tidied away. The file released by the National Archives was due to be kept under lock and key until 2021 but was opened early in response to a request from The Times under the Freedom of Information Act.

Chapter two “Walking into the jaws of destruction again”

Duff Cooper, minister of information, with his wife, Lady Diana CooperTimes Newspapers Ltd

The caste of leaders confronted with the rise in British prejudice belonged to the decadent interwar generation satirised in works such as Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies “walking into the jaws of destruction again”.

Churchill’s first information minister was Duff Cooper, married to the exquisite society beauty and actress Lady Diana Cooper. The politician’s gossipy diaries were edited posthumously by their son, the much loved author John Julius Norwich. Cooper’s great-great nephew is David Cameron.

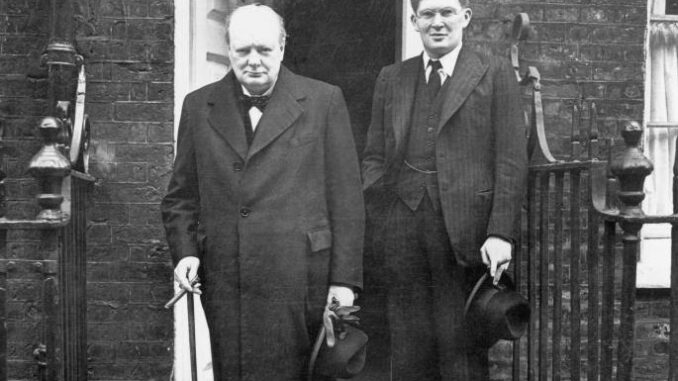

Cooper’s set ranged from the Jewish banking family the Rothschilds to the minor aristocrats the Mosleys, among them the MP Sir Oswald Mosley, known as “Tom” to family and friends. “I can’t bear the Mosleys,” Cooper once confided to his diary, which was protected from prying eyes by a lock. “The sight and sound of them talking their tedious twaddle makes me feel sick.”

When Cole Porter telegrammed him an invitation for dinner at the Ritz, Cooper sat alone in the Piccadilly hotel until it dawned on him that his musical friend had meant the one in Paris. Fred Astaire, Rita Hayworth and Cary Grant added vim to Cooper’s social whirl.

The Coopers attended the Mosleys’ fancy dress barge party in Venice on September 7 1922. According to the diaries, Diana made a friend “up as a Venetian Jew and he looked very well . . . Tom Mosley made a declaration of love to Diana this evening. She told him not to be silly. He said he had adored her all this summer — that he had never felt anything like it in his life before.”

Then there was Brendan Bracken, an Irish Catholic fantasist who entered British high society by pretending to be the orphaned son of Australians who died in a bush fire.

Bracken inspired the character of Rex Mottram, the vacuous colonial adventurer satirised in Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited who, after complaining that he could not taste brandy served in what he derided as a “thimble”, was brought “a balloon the size of his head”.

Winston Churchill with Brendan Bracken Getty Images

Among those fooled by the Irish chancer was Cooper, whose diary entry for January 15 1924 recalls a dinner with Winston Churchill, his wife Clemmie “and a young Australian journalist called Bracken. It was a very enjoyable evening.” Cooper dined at Claridge’s with Anthony de Rothschild, known to him as “Tony Rothschild”.

Sir Oswald ultimately had as little success in seducing the electorate as he did with Cooper’s wife. Losing his seat in the Commons, he founded the British Union of Fascists in 1932. Cooper recalled on February 26 1933: “I attended a debate between Tom Mosley and [James] Maxton [radical Clydesider and leader of the Independent Labour Party] on Fascism v Socialism, in which I thought that Mosley got the best of it.”

When Hitler took power, Jews in Britain were quick to rally. Anthony de Rothschild became founding chairman of the Central British Fund for German Jewry, whose creators read “like a Who’s Who in Anglo-Jewry”, according to Men of Vision, the fund’s history by its late archivist Amy Zahl Gottlieb.

Anthony de RothschildRothschild

Britain had earned a reputation as a haven from persecution. During the 19th century, 140,000 Jews fled here from pogroms. The Jewish-born Benjamin Disraeli became prime minister for the first time as early as 1868. At the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 the Jewish Chronicle proclaimed: “England has been all she could be to Jews, Jews will be all they can be to England.”

The leading Jewish families all “benefited from Britain’s liberalism of the late 19th century, which had granted political emancipation to its Jews”, Gottlieb wrote. “Members of the cousinhood were soon elected to parliament. Some were elevated to the peerage.”

Now Simon Marks of Marks & Spencer, the chief rabbi and the banking brothers Anthony and Lionel de Rothschild set about helping Jews in peril from the Nazis.

Communal tensions peaked with the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, when Jews and locals erected barricades and fought running battles to prevent Mosley’s fascist Blackshirt marchers entering Jewish neighbourhoods in the East End.

In the Kristallnacht emergency, Anglo-Jewry’s fund arranged for 10,000 unaccompanied Jewish children to escape from Hitler to Britain in a humanitarian rescue known as the Kindertransport.

Sir Oswald Mosley inspects members of his British Union of FascistsGetty Images

Cooper stuck out in the 1930s as an opponent of appeasement and was the only cabinet minister to resign in protest against Neville Chamberlain’s popular but doomed Munich agreement with Hitler. Cooper’s friend Noël Coward sent a handwritten note congratulating him on his strength and courage while lamenting how odd and unpleasant it had been “to see thousands and thousands of English people wildly cheering their own defeat”.

Cooper was alert to antisemitism. In the final years of peace, he warned Chamberlain’s secretary of state for war, the Jewish politician Leslie Hore-Belisha (who introduced the eponymous beacons as transport minister) of impending bigotry. The episode is recalled in Kushner’s The Persistence of Prejudice.

Hore-Belisha, who became lifelong friends with Cooper and Lady Diana, wrote in his diary that Cooper predicted that “the military element might be very unyielding and they might try to make it hard for me as a Jew”.

Once war broke out Chamberlain indeed sacked Hore-Belisha because “there was a prejudice against him”.

Hore-Belisha was then vetoed as a potential minister of information by the Foreign Office, whose attitude was summed up by the undersecretary Sir Alexander Cadogan: “Jew control of our propaganda would be a major disaster.”

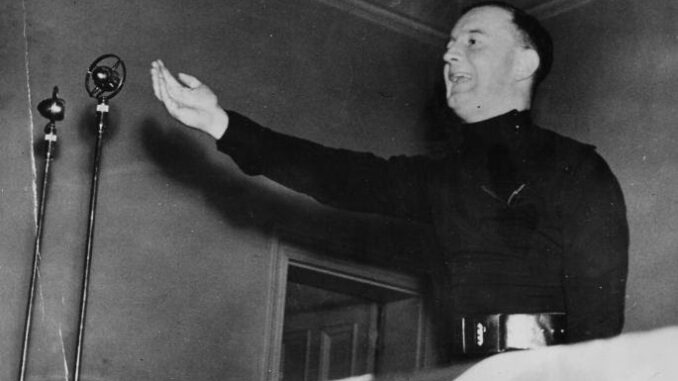

William Joyce, known as Lord Haw-Haw, addressing a fascist meeting in London

Churchill, appointed prime minister in 1940, sent Cooper to run the Ministry of Information. The airwaves were buzzing with Nazi propaganda. As many as six million listeners a night were tuning in to William Joyce, the Hitler enthusiast known as “Lord Haw-Haw”.

The virulent antisemite, known for his catchphrase “Germany Calling”, sought to undermine British morale with broadcasts threatening bombing raids against civilian targets.

“Frequently ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ warned the Eastenders what was coming to them,” recalled R G Burnett in These My Brethren, his history of a mission that tended to London’s poor. “He tried to make their flesh creep — and succeeded.” After the war, Joyce would become the last man hanged for treason against Britain.

Antisemitism in World War Two Britain

Special Branch’s secret summary of anti-Jewish actions from November 1942 to April 1943<

An early warning was sounded of wartime British prejudice. Anthony de Rothschild wrote to “Dear Duff” on March 26 1941 that: “There is an impression that there has been of recent weeks a growth of antisemitism in the country and there is some reason for supposing that it may not be unconnected with enemy propaganda, although this is hard, of course, to establish.<

“Representatives of the Jewish community in London have considered the matter and are naturally perturbed from their own point of view, but it also seems to them that developments on this line help the enemy and damage the war effort.” He suggested a radio broadcast condemning antisemitism as potentially destructive to Britain.

<

<

Anthony de Rothschild’s letter to Duff Cooper warning of the growth of antisemitismNational Archives

Cooper wrote back to “My dear Tony”, stating: “I shall be very pleased to have a talk with you about the important matter.”

Cooper’s position as minister of information was weak. John Julius Norwich recalled: “The appointment was not a success. The press, terrified of censorship, mounted a virulent campaign against him.” Newspapers derided the ministry’s social surveyors, sent out to question the public about morale, as “Cooper’s snoopers”. An Achilles’ heel was that Cooper had allowed the ten-year-old John Julius to be evacuated to safety in America.

Four months after replying to Anthony de Rothschild, Cooper was replaced as minister of information by none other than Churchill’s friend, the imposter Bracken.

There was no doubt where Cooper’s heart lay. He went on to complete a wartime biography of the biblical King David, dedicating it “to the Jewish people to whom the world owes the Old and the New Testaments and much else in the realms of beauty and knowledge: a debt that has been ill repaid”.

Duff Cooper’s reply to Anthony de RothschildNational Archive

The importance attached by Cooper, at the Ministry of Information, to challenging antisemitism never bore fruit. Bracken would be the minister who received Radcliffe’s memorandum recording that prejudice had risen throughout the war.

In northwest England, police in Salford discovered a clandestine basement printing press that was flooding the market with forged clothing coupons. In a confidential memo of April 17 1942, a regional information officer wrote: “Since the Salford coupon case we have observed anxiety among the Jews culminating in the visit of two representative Jews to the regional office.”

Jews believed that they were being discriminated against for jobs: “In spite of the shortage of nurses and the wishes of the Ministry of Health, local authorities are unwilling to employ Jewish girls.”

The official blamed Jews for the prejudice against them: “It appears that the Jewish leaders are so anxious to avoid admitting that ‘The People’ have been especially blameworthy in black markets that they are unwilling to take strong spiritual and communal action. Blindness to facts and alternate periods of arrogance and whines are unlikely to endear the Jewish cause to Britain.” A London civil servant applauded the “reasoned arguments put forward in this memorandum”.

Chapter three. The Ministry of Truth

Senate House in Bloomsbury was the secret headquarters of the Ministry of Information Alamy

The Ministry of Information was secretly housed away from Whitehall in the University of London’s Senate House amid the elegant garden squares of Bloomsbury.

The early skyscraper, when it was opened in 1937, was the second tallest building in the capital, almost as high as St Paul’s Cathedral.

There was hostility to an institution dedicated to such an un-British endeavour as propaganda. The ministry employed some of the finest writing talents of the age, including appointing Laurie Lee as publications editor.

The future poet laureate John Betjeman, working on government films, immortalised in verse his muse “Miss Joan Hunter Dunn”, whom he found there doing the catering. Yet the ministry remained unloved.

Joan Hunter Dunn worked in catering at the Ministry of Information and inspired John Betjeman to write a love poem John Betjeman : A life in pictures

Graham Greene, a recruit, recalled “the high heartless building with complicated lifts and long passages like those of a liner and lavatories where the water never ran hot and the nail-brushes were chained like Bibles. Central heating gave it a stuffy smell of mid-Atlantic except in the passages where the windows were always open for fear of blast and the cold winds whistled in.”

George Orwell’s wife worked in its censorship division, while the author himself broadcast ministry-approved propaganda at the BBC.

In Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, a thinly disguised Senate House served as the Ministry of Truth where Winston Smith worked.

“The Ministry of Truth — Minitrue, in Newspeak — was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air. From where Winston stood it was just possible to read, picked out on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH.”

There has been speculation that Big Brother was deliberately given the same initials as Brendan Bracken.

<

<

The Ministry’s ham-fisted meddling extended to refusing permission for Coward’s classic wartime morale-boosting movie In Which We Serve, with officials complaining that “the film was exceedingly bad propaganda for the Navy, as it showed one of HM’s ships being sunk by enemy action”.

The story was inspired by the loss of HMS Kelly, captained by Lord Mountbatten, who saved the movie by submitting a script to George VI. Filming went ahead after the King wrote that “the spirit which animates the Royal Navy is clearly brought out in the men”. It won an Oscar.

The ministry was quickly closed down in peacetime and replaced by the more modest Central Office of Information.

Chapter four “Nothing to suggest organised activity”

A camp leader ringing the dinner bell for Jewish Kindertransport refugees from Germany and Austria at Dovercourt Bay near Harwich Getty Images

Through much of continental Europe, Jewish people in countries falling to the Nazis were rounded up and sent for slaughter.

Jews in Britain expected the same fate if the Germans invaded. “Some East End Jews, knowing what had been done to their compatriots by the Nazis in Germany, made ready for the coming of Hitler by carrying pellets of poison,” wrote R G Burnett in These My Brethren. “There was a moment when some began to trek out of London, pushing their belongings on handcarts, like the continental refugees in countries overrun by the Germans.”

An Eastender born in 1902 told the Jewish Museum London’s oral histories that he believed that British antisemites would not have bothered to gas Jews, as Hitler had done: “I’ve always maintained it, if they had their way here . . . while you’re alive, they would absolutely chop lumps off you. They wouldn’t wait to put you in a gas chamber, they’d be so eager to get at you.”

The British government’s only wartime acknowledgement of the Holocaust came in 1942 when Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, told the House of Commons that “the German authorities are now carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people in Europe”.

Scepticism remained. Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, chairman of the joint intelligence committee, regarded the reported use of gas chambers as an exaggeration by Jews “to stoke us up”, according to Tony Kushner in The Persistence of Prejudice. “Doubts of the atrocity stories, based on distrust of Jewish sources, continued in government circles until the end of the war,” Professor Kushner wrote.

On June 2 1943, the Lvov ghetto in Poland was liquidated by the Nazis and the last of the city’s 110,000 Jews were sent to a concentration camp.

The same day, it fell to Margaret Corbett Ashby to struggle to sound the alarm about rising antisemitism in Britain.

Mrs Corbett Ashby had begun her political activism campaigning for women to have the vote, creating a group called the Younger Suffragists when she was 18 at the turn of the century.

<

<

Victor Burgess, British fascistNow 61, she was the grande dame of English liberalism and was invited to a meeting of the committee advising Bracken. She confided her concerns that Jews in Britain were facing increasing hostility and prejudice. Doubtless she was heard in respectful silence. Behind her back, though, officials treated her warning with disdain.

One civil servant responded by leafing through issues of the Home Office Special Branch’s fortnightly summary. In a paper marked “Secret” he wrote to a colleague that the following were the only examples of anti-Jewish action that he could find.

•November 15 1942:Large

•January 1-15 1943: A Fascist typewritten broadsheet called The Flame featured antisemitism.

•March 16-31 1943: A pamphlet by R D Lees, who formed a branch of the wartime far-right movement the British National Party in Blackpool, argued that antisemitism was provoked by Jews. He opposed any measures for succouring Jews now under Nazi domination.

•March 1943: Antisemitic slogans chalked and painted on walls and pavements in London districts and in Old Trafford, Manchester. Reference was made to the Jewish connections of Churchill, the foreign secretary Anthony Eden and other public figures. At Hove, typewritten slips bearing the words “Down with the filthy Jews” were found fixed to shop windows of a tobacconist and confectioners, the proprietor of which was Jewish, and to the windows of a Jewish hotel.

•April 1-15 1943:Edward Godfrey of the British National Party bought 1,000 copies of the antisemitic booklet The Truth About The Jews published by Alexander Ratcliffe of the British Protestant League, Glasgow.

•April 16-30:Antisemitic notices such as “burn the Jews” were chalked on five occasions in the Paddington area of west London. Slogans were chalked on a wall in Old Trafford.

The civil servant wrote: “You will agree that there is nothing in all this to suggest anything in the nature of organised activity, at any rate on an important scale.”

A scrawled response to the typed memorandum states: “I did not think that Mrs Corbett Ashby’s account showed signs of careful consideration.”

Nearly all the Jews from Lvov would be killed by November.

Once the war ended, there was a price to pay for the British authorities’ tolerance of antisemitism.

A shop in London run by Victor Burgess, who had been temporarily interned as a suspected enemy sympathiser under the same defence regulations as Sir Oswald and his wife Lady Diana Mosley, was issuing “anti-Jewish propaganda”, officials were told in January 1945. The Home Office was alerted but did nothing. Burgess persisted to become a notorious post-war fascist orator.

Lady Diana Mosley speaking at a meeting on behalf of Sir Oswald Mosley’s Fascist party in 1934PA

Returning from the war, appalled Jewish ex-servicemen formed the 43 Group, which physically smashed up Mosley’s gatherings and attacked fascists and antisemites. “Any six of us was more than a match for 20 of them. We never failed, we always won. We always closed their meetings down, never failed to close a meeting down,” Len Sherman, a martial arts expert from the Welsh Guards, told the Jewish Museum London’s oral history collection.

In 1947 anti-Jewish riots spread through many parts of Britain, triggered by the hanging of two British sergeants in Palestine by the Irgun, an insurrectionary Jewish paramilitary group. A crowd of 700 broke windows at Jewish-owned shops in Eccles, Manchester. Anti-semitic slogans and the fascist sign were daubed on a synagogue in Plymouth. There were days of rioting in Liverpool. Slaughtermen at Birkenhead refused to handle kosher meat.

Officials had turned a blind eye to latent antisemitism throughout the war. When the Ministry of Information staged a touring show, The Evil We Fight, highlighting Nazi atrocities to rouse the public against Hitler in 1944, copies of a subversive pamphlet were found stuffed into exhibition screens.

<

<

The typewritten, two-page tract warned that parliament was controlled by “The City of London International Jew Finance” and rejoiced that “Hitler is ridding the world of Jews and Judaism”. Condemning the British authorities, it said: “They lock up Fascists who at least want Britain for the British and clear the country of these slimy, oily, greasy, immoral Jewish dagoes . . . ANTI-SEMITISM MUST BE ENCOURAGED! Britain for the British and to Hell with Jews and all other alien swine.”

One official wrote: “It is my opinion that the open letter to Fellow-Britons is not antisemitism — it is pure German propaganda. Antisemitism is merely a part of the whole.”

Another commented in a handwritten note that it was childish nonsense which left him quite unconcerned. At the Ministry of Information, they kept calm and carried on.

The more I read about Churchill, the more I dislike the two-faced bastard. He never did anything but sabotage us whenever he was actually in a position to help, empty verbiage aside.

“Bracken’s predecessor, Duff Cooper, supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine and had resigned from prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s cabinet in protest of the 1938 Munich Agreement which appeased Hitler’s aggression towards Czechoslovakia. In early 1941, Anthony de Rothschild, who had founded the Central British Fund for German Jewry to assist the Nazis’ first victims, wrote to him laying out the UK community’s anxieties.

“There is an impression that there has been of recent weeks a growth of anti-Semitism in the country and there is some reason for supposing that it may not be unconnected with enemy propaganda, although this is hard, of course, to establish,” de Rothschild argued.

“Representatives of the Jewish community in London have considered the matter and are naturally perturbed from their own point of view, but it also seems to them that developments on this line help the enemy and damage the war effort,” he wrote.

He proposed a radio broadcast labeling anti-Semitism as a threat to Britain.

Cooper’s response was warm. “My dear Tony,” he began, “I shall be very pleased to have a talk with you about the important matter.” Four months later, however, Churchill moved him to another government post.”

– “As Holocaust raged, UK officials blamed Jews for rising wartime anti-Semitism

A classified file recently released to a British newspaper lifts the lid on complacency and prejudice at the heart of Winston Churchill’s propaganda ministry”

By ROBERT PHILPOT

25 August 2018, 4:32 am

https://www.timesofisrael.com/as-holocaust-raged-uk-officials-blamed-jews-for-rising-wartime-anti-semitism/