The party’s new leadership has taken an aggressive stance on litigation. Money woes and legal realities cloud the effort’s chance of success.

By Patrick Marley, Josh Dawsey, Yvonne Wingett Sanchez and Isaac Arnsdorf, WSJ March 22, 2024

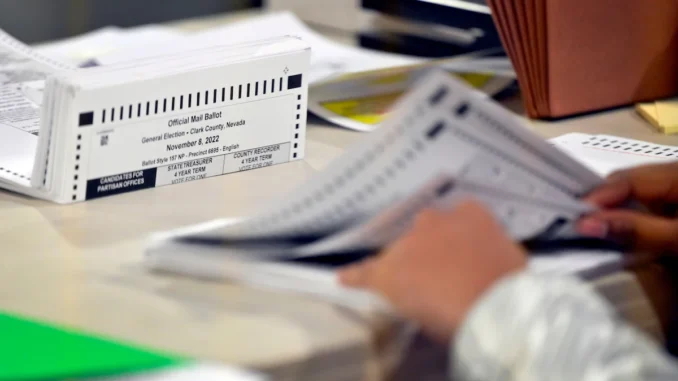

Election workers process mail-in ballots at the Clark County Election Department on Nov. 8, 2022, in North Las Vegas, Nev. (David Becker for The Washington Post)

Donald Trump installed a new chairman of the Republican Party this month, he explained privately and publicly what he wanted from the GOP: a bigger focus on election-related lawsuits, a more aggressive operation to monitor voting and a vow to make “election integrity” the party’s No. 1 priority.

The party is now striking a more aggressive tone as it recruits poll observers to keep an eye on in-person voting and boasts of positioning thousands of lawyers to challenge ballots and bring lawsuits. The strategy — an outgrowth of the one it used both before the 2020 election and after, when Trump sought to overturn the result — is meant to please Trump, electrify the base and persuade judges to tighten voting rules.

“It’s an extremely high priority for the president,” said the new Republican National Committee chairman, Michael Whatley, referring to Trump.

But the reality of what Republicans can achieve may not match Trump’s desires. Democrats have raised huge sums to fight Republican efforts, even as the GOP remains cash-strapped.

And the legal terrain is more settled now than it was four years ago, when courts had to weigh in on how to conduct voting during the height of the coronavirus pandemic. That leaves fewer opportunities to change the rules through the courts.

“Courts are a lot less tolerant of bringing cases now that could have been brought before,” said Justin Levitt, a Loyola Law School professor who previously advised the Biden White House on voting rights. “A raft of new litigation over the summer is going to run into an awful lot of: ‘The things you’re protesting aren’t new. Where were you a couple of years ago?’”

This year could be just as intense. Trump continues to baselessly maintain that the 2020 election was rigged and has repeatedly complained about “election interference” in 2024 as he faces a slew of criminal and civil cases.

Both parties are actively raising money to fund election-related litigation. Between January 2021 and June 2023, the parties and related entities raised three times as much for election litigation as they had for the equivalent period in the last election cycle, according to data from the Federal Election Commission.

But the case was assigned to a judge who had thrown out a similar complaint three weeks ago, ruling the state was following federal law.

The campaign and legal messaging for Republicans is delicate. Trump has long contended, without evidence, that early-voting methods are a source of fraud that allows Democrats to rig elections. Whatley, like his predecessor Ronna McDaniel, is encouraging Republicans to vote by mail or vote early in person, even as the RNC and its allies try to persuade judges to throw out more mail ballots in battleground states.

Whatley said the RNC’s legal efforts are both about filing lawsuits before the election and having an apparatus to challenge results if needed. He said the party will have “thousands” of lawyers in place for after the election.

“We want to be in the room when votes are being cast and counted,” Whatley said.

The RNC launched its litigation and poll-watching initiative in 2021 with much fanfare, marking the expiration of a decades-old court order that restricted the committee from directly operating at polling locations. For the midterm elections, the party dispatched officials to battleground states to coordinate with local groups and recruit poll workers and poll watchers who were supposed to help document irregularities and report them to lawyers standing by to mount legal challenges.

Whatley said the RNC’s litigation focuses on four main categories — mail voting, voter rolls, noncitizen voting and voter ID. Before he was named RNC chairman, Whatley served as general counsel for the RNC and chairman of the Republican Party of North Carolina, where he said he assigned 500 attorneys to watch the vote in 2020.

“It’s a model that we’re going to put in place nationally,” Whatley said.

McDaniel, Whatley’s predecessor, had acknowledged Biden won while also playing up doubts about the fairness of the 2020 election. Trump griped that she did not do enough to change the results, people familiar with their relationship said, or to block laws from being changed in 2020, one factor in her departure this year.

Bobb worked in front of the camera and behind the scenes to undermine Biden’s win in 2020. In Arizona, she helped Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani arrange a meeting that aired false assertions of mass election fraud and later promoted a review of 1.1 million ballots in the state’s most populous county that election experts widely discredited as unreliable.

Benjamin Ginsberg, a longtime Republican election attorney who represented George W. Bush’s campaign during Florida’s 2000 recount, described Spies as seasoned and reasonable and Bobb as an “unguided missile.”

Ginsberg said the election lawsuits that Republicans and Democrats are filing often are aimed less at winning in court and more at boosting fundraising and getting their supporters to the polls. As a result, the public has less faith in elections, he said.

“If more evidence-free lawsuits are filed based only on the belief that the other side is rigging the election, it will be increasingly difficult for whoever wins to actually govern,” Ginsberg said.

Some of the lawsuits from both sides may affect only a small number of ballots, if that, but could nonetheless be meaningful in states decided by narrow margins.

In Pennsylvania, judges are weighing whether election officials must count absentee ballots that are improperly dated. In Wisconsin, they are considering absentee voting policies and the legality of ballot drop boxes.

In Arizona, the RNC is suing to invalidate the state’s highly technical, 200-plus-page manual that spells out the rules for running elections. The lawsuit says the public should have been given more time to weigh in on it and alleges it conflicts with state law because it allows out-of-precinct voting, among other reasons.

One of the most closely watched cases is in deep-red Mississippi. There, the RNC is seeking to toss a state law that allows mail ballots to be counted if they are postmarked by Election Day and received up to five days later. The RNC argues all ballots must be received by Election Day and could use the lawsuit as a test case to try to knock down similar laws in other states.

With its lawsuit in Michigan, the RNC is claiming the state is not doing enough to maintain its voter rolls and must quickly remove the names of the deceased and ineligible voters. The case is being heard by U.S. District Judge Jane M. Beckering, who this month threw out a similar lawsuit, noting that “Michigan is consistently among the most active states in cancelling the registrations of deceased individuals.”

Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (D) said the RNC’s lawsuit is a reminder of the relentless attacks on the 2020 results in Michigan and other swing states. She said those who brought it were engaged in “a strategy of trying to sow seeds of doubt in our elections to potentially overturn them in the future.”

“It’s 2020 redux,” she said. “It certainly feels like here we go again.”

Clara Ence Morse contributed to this report.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.