Israeli officials have regularly called for a ‘credible military threat’ against Tehran’s nuclear facilities, but less discussed is the major conflict that’s almost sure to follow

By JUDAH ARI GROSS, TOI 3 December 2021, 6:40 am

In this photo released by the US Air Force, an Israeli Air Force F-15 Strike Eagle flies in formation with a US Air Force B-1B Lancer over Israel as part of a deterrence flight Saturday, Oct. 30, 2021. (US Air Force/Senior Airman Jerreht Harris via AP)

Nearly one year ago, IDF chief Aviv Kohavi stood on stage at an Institute for National Security Studies conference in Tel Aviv and announced that he had ordered the military to begin preparing renewed plans for a strike on Iran’s nuclear program.

“Iran can decide that it wants to advance to a bomb, either covertly or in a provocative way. In light of this basic analysis, I have ordered the IDF to prepare a number of operational plans, in addition to the existing ones. We are studying these plans and we will develop them over the next year,” Kohavi said.

He added: “The government will of course be the one to decide if they should be used. But these plans must be on the table, in existence and trained for.”

Since then, the IDF has done just that, with the air force and Military Intelligence, in particular, preparing themselves for such an operation, stepping up training exercises and focusing tremendous resources on intelligence collection. Billions of additional shekels have been poured into the defense budget specifically to prepare for strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities.>

And over the past year, Israeli officials have regularly repeated calls for what they describe as a “credible military threat” against Iran’s nuclear program, in speeches, press conferences, media interviews and private meetings with allies, arguing that it is necessary in order to gain leverage in the ongoing negotiations with the Islamic Republic over its nuclear program.

By its own estimates, the IDF is still at least months away from being fully prepared to conduct such a strike, though officials say that a more limited version of its plans could be carried out sooner.

An Israeli F-35 fighter jet takes off during the military’s Blue Flag exercise in October 2021. (Israel Defense Forces)

But the focus of these discussions has generally been on the strike itself against Iran’s nuclear facilities, an operation that would indeed be far, far more complicated and difficult than any other the IDF has conducted, including its raids to target Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981 and Syria’s in 2007.

In each of those missions — Operation Opera and Operation Outside the Box — a single sortie containing a relatively small number of fighter jets conducted the bombing. But unlike in both of those cases, Iran does not have one nuclear facility that one group of planes could take out in a single strike, but many that are spread throughout the country, which would therefore require extraordinary levels of coordination to ensure that all of the sites were hit at the same time.

Making this more difficult is the fact that many of the facilities are buried deep underground, making them all but impenetrable to attacks from the air, particularly the Fordo reactor, where Iran recently began enriching uranium to 20 percent levels of purity with advanced centrifuges, in the latest breach of the 2015 nuclear deal.

The United States does have the massive bunker-busting ordnances needed to strike such facilities — the 13,600-kilogram (30,000-pound) GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) — but Washington has so far refused to provide them to Israel. In any case, what’s more, selling the incredibly heavy bomb to Jerusalem would not do much good, as the Israeli Air Force does not have an aircraft capable of carrying it, and nor does it even have the airfield infrastructure needed to support the aircraft that could carry it.

(To circumvent these limitations and to demonstrate the seriousness of an Israeli threat of attack, some current and former officials in the US have floated the idea of selling or leasing to Israel one of the three American heavy bombers capable of carrying the MOP — the B-52, B-1, or B-2. Doing so, however, faces a number of legal and logistical challenges, as the B-52 and B-2 are both effectively barred from sale under America’s New START treaty with Russia and the B-1 may also not be fully capable of containing the MOP within its bomb bays.)

Illustrative: A US Air Force B-1B bomber, left, flies with a South Korean fighter jet F-15K over the Korean Peninsula, South Korea, Sunday, July 30, 2017 (South Korea Defense Ministry via AP)

Iran has also invested heavily in its air defenses, both purchasing advanced systems from Russia and developing its own domestically produced capabilities.

But while the complexities of an Israeli operation should not be overstated, they are ultimately problems that can be resolved with enough time and resources.

After a strike

Though Israeli officials are willing to discuss the efforts to overcome these challenges and develop the capabilities needed to conduct such a strike, typically left unmentioned is what happens afterward, which is of far greater significance.

In 1981 and in 2007, there was effectively no immediate retaliation by Iraq and Syria, respectively, though Baghdad’s response did come a decade later — to a certain extent — with its Scud missile attacks on Israel during the First Gulf War. This is not expected to be the case with Iran, several Israeli defense officials have told The Times of Israel.

For decades, Tehran has been building up a number of proxies throughout the region, the most formidable of which is Lebanon’s Hezbollah, a terrorist group with an arsenal of rockets, missiles and mortar shells that matches and even surpasses many Western states’. These foreign proxies are meant to insulate Iran from attack by its enemies. To wit: Israel can’t attack Iran if it is busy fighting off rocket fire and invasion attempts by Hezbollah from Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia similarly couldn’t attack Iran if it were facing the Houthis in Yemen.

Hezbollah fighters stand atop a car mounted with a mock rocket, as they parade during a rally to mark the seventh day of Ashoura, in the southern village of Seksakiyeh, Lebanon, in this October 9, 2016 photo. (Mohammed Zaatari/AP)

The Israeli military firmly believes that this network of proxies would be brought to bear against Israel if it conducts a strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities. And Israeli projections for what a war against Hezbollah and allied militias in the region would look like are unnerving: thousands of projectiles raining down on Israeli population centers, hundreds killed, severe damage to infrastructure and major utilities knocked out of service.

That is not to say that Israel would never conduct a strike on Iran for fear of attack from its proxies, but that any decision to do so would have to be weighed not against the military’s ability to carry out the operation, but against the potentially devastating prospects of what would follow the raid.

“The military option needs to be on the table. It is, of course, the last thing that we want to use, but we don’t have the luxury of not preparing ourselves for the options,” Defense Minister Benny Gantz said Thursday, in an on-camera interview with the Ynet news site.

Jerusalem’s concern is that a nuclear-armed or even nuclear-threshold Iran would be able to act with even greater impunity in the region, arming its proxies and more deeply entrenching itself in Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq.

But Israeli officials have been loath to set a specific condition under which it would conduct a strike. This is due, in part, to the fact that the considerations lie not only in Iran’s capabilities, but in the balance between the threats facing Israel and Israel’s ability to counter them.

Asked if uranium enrichment to the level of 90 percent purity — generally regarded as “weapons-grade” — would prompt an Israeli attack, Gantz refused to comment on Thursday.

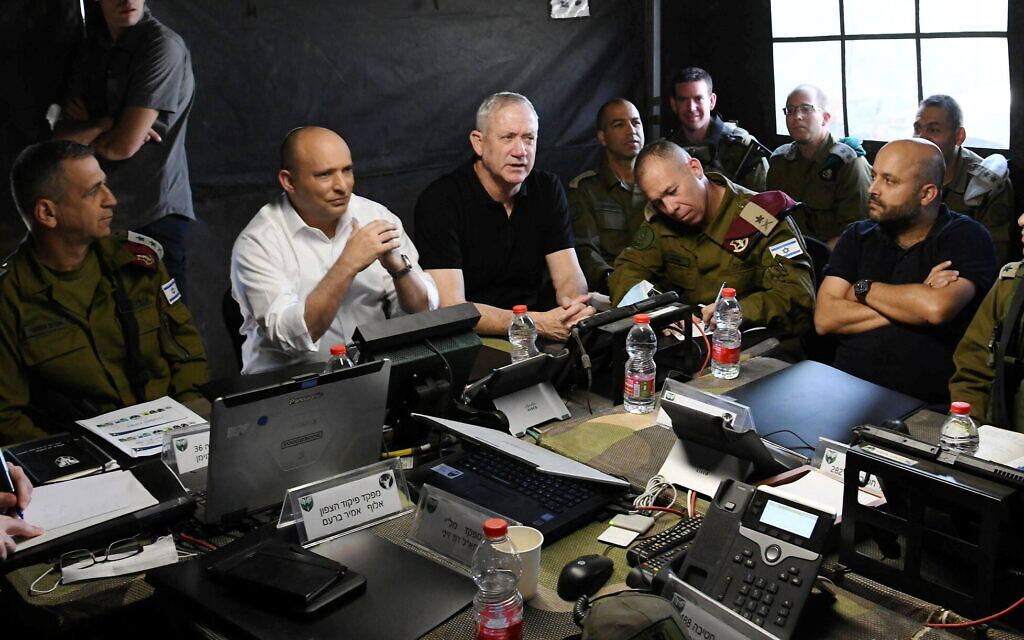

From left to right: IDF Chief of Staff Aviv Kohavi, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Defense Minister Benny Gantz attend a military drill in northern Israel on November 16, 2021. (Amos Ben-Gershom/GPO)

“I don’t like setting red lines that afterward I’d have to come and explain myself [if I didn’t uphold them]. We are tracking the Iranian process every day. There will be a point in time when the world, the region, and the State of Israel will have no choice but to act,” he said.

The Israel Defense Forces has been making strides to prepare itself for the multi-front war that is liable to follow a strike on Iran, holding a number of large-scale exercises simulating such a conflict in recent months and investing roughly NIS 1 billion ($315 million) toward training for next year. The military is also working to improve its air defenses, particularly in northern Israel, in an effort to prevent the worst of the damage from rocket barrages and drone strikes in a future conflict.

But the propensity of Israeli officials to discuss the technical aspects of an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities belies the true calculus at play in deciding whether to carry it out: it’s not about the strike, but the war that follows.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.