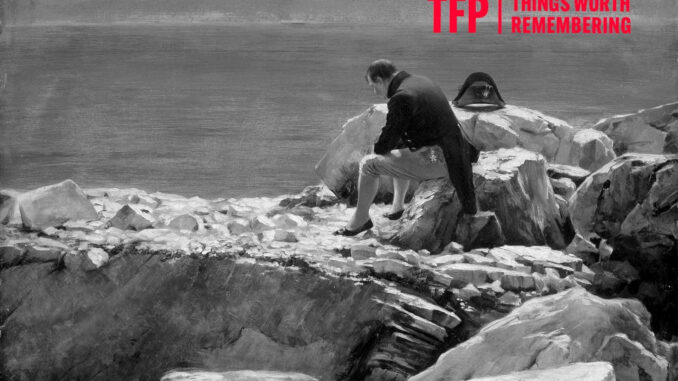

It’s Over, Napoleon | in St. Helena, by Oscar Rex. Emperor Napoleon in exile. (Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Welcome to Douglas Murray’s column, Things Worth Remembering, in which he presents great speeches from famous orators we should commit to heart. To listen to Douglas read from and reflect on British prime minister William Pitt’s June 1799 speech on the danger of Napoleon, scroll to the end of this piece.

On a recent flight, I struggled to make it through Ridley Scott’s 2023 Napoleon. I admired the battle scenes and wondered about Joaquin Phoenix’s accent, but, most of all, I missed not seeing one of Napoleon’s biggest nemeses: British prime minister William Pitt.

Pitt the Younger, as he was known (his father was prime minister before him), became the youngest ever prime minister of England at the age of just 24. Following the union of Britain and Ireland in 1800, he went on to become the first prime minister of the new United Kingdom.

It is an extraordinary thing to think of now, and though the rotten political system of his day threw up many rotten people, Pitt was not among them. He turned out to be the right man at the right—if rather early—time.

Some years ago, I picked up a volume of Pitt’s War Speeches, published in Oxford in 1916.

There is an addendum to that volume from the editor, one Reginald Coupland, who notes after the final speech that “At the present time (April 1915) no epitaph on William Pitt could sound to the ears of his countrymen more appropriate than the words spoken by Pericles of the Athenians who had died for Athens in the war with Sparta.”

The editor goes on to quote part of the great speech that I covered here last month (“The whole earth is the tomb of famous men”).

The addendum is a reminder of two things: great speeches and great speechmakers inevitably reach back to the greats of the past; but also, they reach forward into the future.

William Pitt, being an educated man who could read Latin and ancient Greek, knew, of course, all about the past, and the lessons Britain might glean from it—especially as he faced down the mounting threat posed by Napoleon just over the Channel.

The late 1790s were desperate times for England. France’s soon-to-be emperor was preparing to seize power in Paris and launch a series of wars that would lead to a continent-wide empire the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the rise of Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire 1,000 years before.

It seemed, from the vantage point of London, an insuperable problem—one that England, still reeling from its loss of the American colonies, was in no position to tackle.

Napoleon, as Pitt the Younger understood all too well but so many of his compatriots did not, was a life force—apparently immune from the normal rules of governance and war, and demanding of a certain admiration, however terrible his actions may have been. He defied easy categorization, and it was never easy to write him off as entirely one thing or the other. Yes, he posed a dire threat to the balance of power, and his ambition and recklessness were likely to cost countless British lives.

But it was incorrect to dismiss him as simply a force for evil. He was more complicated than that—a function of long-fomenting historical and philosophical forces. After so many years of revolution and upheaval, the collapse of the ancien régime, the Terror, the guillotine, the razing of old estates and institutions, the French were not entirely wrong in placing their hopes in a strongman who might restore not only a sense of stability but nobility to la patrie.

I remember lunch many years ago with a former head of the French military, an admiral in the French Navy, during which he asked me if it was true that British schools still taught that Napoleon was a sort of proto-dictator, almost a proto-Hitler. I confirmed that yes, to the extent that British schoolchildren were taught anything, that was true.

“Mon Dieu,” I remember him saying, horrified.

And it is true that the difference of attitude even today, between one side of the English Channel and the other, regarding this most famous son of France (witness his great tomb in Paris), is a reminder that even a small stretch of water can lead people to see history in wholly different lights.

In any case, William Pitt needed to raise the alarm and to persuade Parliament and the people that the cause of opposition to Napoleon—no matter how complicated a historical figure he might have been—was necessary and just.

It is Pitt’s speech from June 7, 1799, that often resonates with me—and reminds one of the second part of that lovely addendum penned by Reginald Coupland in the middle of the Great War, that the great speech not only looks back but forward, that it inspires for many ages to come, long after the speechmaker is dead and buried, perhaps to inspire another wartime prime minister, a century and a half later.

The speech is about Britain’s alliance with Russia, and it tells us as much about tyrants then as it does about tyrants now. Some in Westminster criticized Pitt for not only trying to stop French dominance but for trying to change the political opinions of France—to make the French rethink the wisdom of embracing a tyrant who, in the end, as Pitt could see so well, would lead to death and destruction and the bulldozing of the very culture the French claimed to care so much about.

To these criticisms, Pitt responded by noting: “We are not in arms against the opinions of the closet nor the speculations of the school. We are at war with armed opinions. We are at war with those opinions which the sword of audacious, unprincipled, and impious innovation seeks to propagate amidst the ruins of empires, the demolition of the altars of all religion, the destruction of every venerable and good and liberal institution.”

In other words, this is not some academic back and forth. This is not about philosophies of history, war, or life. We are not debating for the sake of debating, Pitt shows. We are arguing over meanings and values and aspirations, and whoever wins this debate will influence the tide of history.

Pitt went on to say:

Whilst the principles avowed by France, and acted upon so wildly, held their legitimate place confined to the circles of a few ingenious and learned men; whilst these men continued to occupy those heights which vulgar minds could not mount; whilst they contented themselves with abstract inquiries concerning the laws of matter or the progress of mind, it was pleasing to regard them with respect; for, while the simplicity of the man of genius is preserved untouched, if we will not pay homage to his eccentricity, there is, at least, much in it to be admired. Whilst these principles were confined in that way and had not yet bounded over the common sense and reason of mankind, we saw nothing in them to alarm, nothing to terrify. But their appearance in arms changed their character. We will not leave the monster to prowl the world unopposed. He must cease to annoy the abode of peaceful men. If he retire into the cell, whether of solitude or repentance, thither we will not pursue him; but we cannot leave him on the throne of power.

Ironically, Murray’s quotation from Pitt the Younger;s speech lends to the claims of recent sympathetic biographers of Napoleon that he was not the aggressor in what are known as the Napoleonic wars, but England and its allies were the aggressors. According to this narrative, Napoleon’s invasions of other European countries were necessary to defend France from English Aggression. I find this narrative to strain credibility. But Pitt’s speech, as quoted by Murray. does make it plausible. Napoleon was not, as far as I know, at war with England at the time when Pitt the Younger declared war on him.

Letter to the Jewish Nation from the French Commander-in-Chief Buonaparte

General Headquarters, Jerusalem 1st Floreal, April 20th, 1799,

in the year of 7 of the French Republic

BUONAPARTE, COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE ARMIES OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

IN AFRICA AND ASIA, TO THE RIGHTFUL HEIRS OF PALESTINE.

Israelites, unique nation, whom, in thousands of years, lust of conquest and tyranny have been able to be deprived of their ancestral lands, but not of name and national existence !

Attentive and impartial observers of the destinies of nations, even though not endowed with the gifts of seers like Isaiah and Joel, have long since also felt what these, with beautiful and uplifting faith, have foretold when they saw the approaching destruction of their kingdom and fatherland: And the ransomed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with songs and everlasting joy upon their heads; they shall obtain joy and gladness and sorrow and sighing shall flee away. (Isaiah 35,10)

Arise then, with gladness, ye exiled ! A war unexampled In the annals of history, waged in self-defense by a nation whose hereditary lands were regarded by its enemies as plunder to be divided, arbitrarily and at their convenience, by a stroke of the pen of Cabinets, avenges its own shame and the shame of the remotest nations, long forgotten under the yoke of slavery, and also, the almost two-thousand-year-old ignominy put upon you; and, while time and circumstances would seem to be least favourable to a restatement of your claims or even to their expression ,and indeed to be compelling their complet abandonment, it offers to you at this very time, and contrary to all expectations, Israel’s patrimony !

The young army with which Providence has sent me hither, let by justice and accompanied by victory, has made Jerusalem my head-quarters and will, within a few days, transfer them to Damascus, a proximity which is no longer terrifying to David’s city.

Rightful heirs of Palestine !

The great nation which does not trade in men and countries as did those which sold your ancestors unto all people (Joel,4,6) herewith calls on you not indeed to conquer your patrimony ;nay, only to take over that which has been conquered and, with that nation’s warranty and support, to remain master of it to maintain it against all comers.

Arise ! Show that the former overwhelming might of your oppressors has but repressed the courage of the descendants of those heroes who alliance of brothers would have done honour even to Sparta and Rome (Maccabees 12, 15) but that the two thousand years of treatment as slaves have not succeeded in stifling it.

Hasten !, Now is the moment, which may not return for thousands of years, to claim the restoration of civic rights among the population of the universe which had been shamefully withheld from you for thousands of years, your political existence as a nation among the nations, and the unlimited natural right to worship Jehovah in accordance with your faith, publicly and most probably forever (JoeI 4,20).