In 1951, a book by an unschooled dockworker predicted the forces that would give rise to radical politics on the left, populism on the right—and a president like Donald Trump.

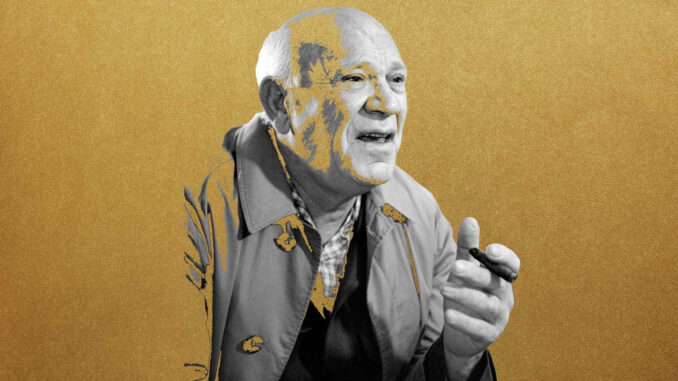

(Illustration by Pablo Delcan for The Free Press, photo via Getty Images)

Welcome back to The Prophets, our Saturday series about fascinating people from the past who foresaw our current moment. Last week, Louise Perry wrote about Andrea Dworkin, the feminist who imagined—with uncanny clarity—how our world would be shaped by online pornography.

Today, Rob Henderson celebrates Eric Hoffer, the blue-collar philosopher who explained how mass movements form, and warned about a society ruled by elites.

For more than 70 years, a slender volume written by a dockworker who died in 1983 has been handed around by presidents, would-be presidents, journalists, students, and more as a guide—decade after decade—to epochal and baffling events.

Published in 1951 in the shadow of World War II and the rise of the Soviet Union, Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements became one of President Dwight Eisenhower’s favorite books. As the former Supreme Allied Commander of European forces during World War II, Eisenhower saw firsthand the rise of mass movements and how they turn destructive. During one of the nation’s first televised presidential press conferences, Ike cited the book, turning it into a bestseller.

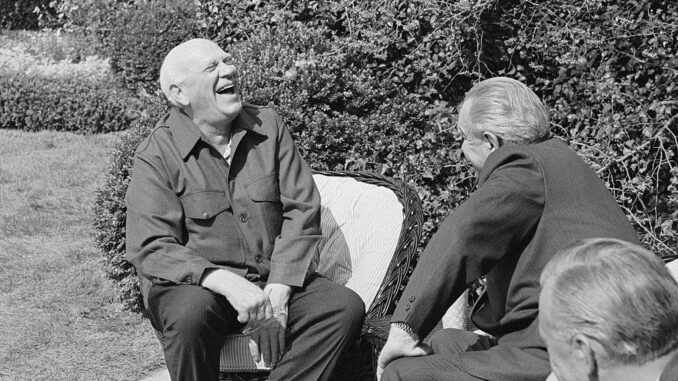

Hoffer, often called “the longshoreman philosopher,” was admired across the political aisle. In 1967 he was an overnight guest of President Lyndon Johnson at the White House. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Years after Hoffer’s death, his book was rushed back into print and sold briskly when, in the new millennium, people turned to The True Believer to explain the attacks of 9/11. Decades before the terrorists commandeered the planes, Hoffer wrote:

All the true believers of our time declaimed volubly. . . on the decadence of the Western democracies. The burden of their talk is that in the democracies people are too soft, too pleasure-loving, and too selfish to die for a nation, a God, or a holy cause. This lack of a readiness to die, we are told, is indicative of an inner rot—a moral and biological decay.

Since then, journalists have cited the book as a source to explain both the creation of the Tea Party on the right and the Occupy Wall Street movement on the left.

In 2016, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, to better understand her opponent Donald Trump and his followers, read what she later wrote was Hoffer’s “exploration of the psychology behind fanaticism and mass movements, and I shared it with my senior staff.”

For readers today, Hoffer’s descriptions of the nature of these movements and the people who join them are timelier and more trenchant than ever. The book—the paperback edition is fewer than 170 pages—is divided into 125 “chapters” ranging from a few sentences to several pages. These are mostly epigrammatic observations that build into a portrait of the personalities and forces that create mass movements.

As The Wall Street Journal wrote: “If you want concise insights into what drives the mind of the fanatic and the dynamics of a mass movement at their most primal level, may I suggest an evening with Eric Hoffer.”

Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements became one of President Dwight Eisenhower’s favorite books. (Harper Perennial Modern Classics)

I first learned of The True Believer in the summer of 2020. I was out of the U.S. getting my PhD in psychology at the University of Cambridge. I had already begun publishing my own social observations, which led to an interview with a Dutch media outlet on cancel culture. The interview was posted and got a lot of views, which prompted the head of the outlet to take it down because he felt I was too sympathetic to the canceled.

I wrote a piece in Quillette on the irony of being canceled for expressing my thoughts on the canceled, and noted, “The U.S. used to export Coca-Cola, television shows, and music. Today, we export outrage, deplatforming, and social mobbing.”

A fellow student in my program saw the piece and told me I had to read The True Believer. I did, and like Eisenhower, it quickly became one of my favorite books. There were passages—published in 1951!—that seemed to describe how the rise of intellectual and social orthodoxy on campus, and across a growing number of institutions, stifles debate and free expression. More than that, Hoffer captured how in the age of smartphones and social media, people fear the consequences of uttering a single wrong word. He wrote:

[I]n a mass movement, the air is heavy-laden with suspicion. There is prying and spying, tense watching, and a tense awareness of being watched. The surprising thing is that this pathological mistrust within the ranks leads not to dissension but to strict conformity. Knowing themselves continually watched, the faithful strive to escape suspicion by adhering zealously to prescribed behavior and opinion. Strict orthodoxy is as much the result of mutual suspicion as of ardent faith.

He warned in The True Believer, and in later books and interviews, about the dangers for American society of the rise of the intellectual elites. A biographer of Hoffer, Tom Bethell, quotes Hoffer saying that nowhere else was there “such a measureless loathing of their country by educated people as in America” and that this elite want America to be “not a melting pot but a seething cauldron.” These self-anointed experts sought a society “in which planning, regulation, and supervision are paramount, and the prerogative of the educated.”

Hoffer also described how language gets enlisted as a marker of who really is a true believer:

Simple words are made pregnant with meaning and made to look like symbols in a secret message. There is thus an illiterate air about the most literate true believer. He seems to use words as if he were ignorant of their true meaning. Hence, too, his taste for quibbling, hair-splitting, and scholastic tortuousness.

I wonder what Hoffer would make of a world in which some words are so pregnant with meaning that the phrase “pregnant women” has become verboten.

He was born—well, we don’t know exactly where or when he was born. In Tom Bethell’s entertaining and dogged biography, Eric Hoffer: The Longshoreman Philosopher, Bethell says no record of his birth has ever been found, and estimates Hoffer was born between 1898 and 1902.

It was as if Hoffer came into being one day in his mid-thirties in the agricultural fields of California’s hinterlands, because the first documented evidence of Hoffer’s existence was when he arrived in 1934 at a Depression-era federal camp for the transients in El Centro, California.

From there he held a series of itinerant jobs: migrant worker, gold miner, construction worker, dishwasher.

I didn’t know, when I first read The True Believer, that he and I both spent our early years doing manual labor in the largely ignored parts of California. I was born in the state and had a nomadic early childhood, being moved in and out of a series of foster homes, until I was adopted and brought to the small inland city of Red Bluff. There, as a teenager, I held a series of minimum-wage jobs such as dishwasher at a restaurant and shelf stocker at a grocery store. I describe my experiences in my recent memoir, Troubled.

So I know how strange childhoods can be. But Hoffer’s bare bones account of his life prior to his appearance in California in 1934 has the quality of a fairy tale.

The details change in his various tellings, but the outlines are this: he was born in New York to Alsatian parents—thus his lifelong Germanic accent. Then when he was seven years old his mother died and he went blind.

Here’s Hoffer, in a 1963 conversation with James Day, the general manager of KQED in San Francisco, discussing literacy, tradesmen, and intellectuals:

When he was 15, his sight miraculously returned. Because of his blindness, he had no schooling, but he became a voracious reader, thrilled by the gift of seeing words on a page. At age 18 his father died, and Hoffer set out alone for the West Coast.

Bethell makes a convincing case it is just a tale. And he offers a plausible reason for Hoffer telling it. Bethell thinks Hoffer was not born in the U.S. but came here illegally from Germany as an adult. If he did, he arrived during the Depression at a time of mass deportation of people without documentation. Being here illegally would also explain why Hoffer refused to apply for a passport and never left the country, even after he became famous.

In an interview with Bethell, Hoffer made this self-revealing quote: “Consider the lengths people will go to come here. And who built this country? Really, nobodies. Nobodies. Tramps.”

But there is one confirmable truth in his account: the hunger for books. I had the same experience of discovering books, and finding they opened the idea of a larger world to me. Whenever I felt down, it was soothing to read about others who had experienced hardship and found ways to rise above it.

Even the parts of Hoffer’s life story that can be confirmed retain a fable-like quality. Eventually this manual laborer found a permanent job on the docks of San Francisco. It gave him stability and a sufficient salary to afford a studio apartment, with a plank for a desk, the kind of spartan dwelling he occupied for the rest of his life. There he consumed the works of the greatest thinkers in history, and he wrote their most trenchant observations on 3 × 5 cards. He spent years reading and rereading, shuffling the cards, and adding his own insights. All this resulted in the distillation of the wisdom of others that he transmuted into something original.

In 1942, Bethell writes, Hoffer sent an unsolicited manuscript that grew from his notes to a magazine called Common Ground. The editor, Margaret Anderson, wrote back a rejection letter, but offered him encouragement to keep writing. In 1949 he sent Anderson the manuscript of the book he called Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. She passed the book to the editor of a publishing house and suggested it be retitled The True Believer. To Bethell’s knowledge, Hoffer and Anderson met only once; Hoffer dedicated the book to her.

It was a success. As Bethell writes, “The contrast between his debut as a literary stevedore—a publicity photograph showed him in his familiar working-class rig—and his learned abstractions and footnoted references was without precedent in American letters. It was also irresistible to the press.” Although Hoffer wrote 10 books, the impact of his first has been most enduring.

Hoffer kept his job on the docks, even after writing a bestseller, until he was forced to retire in the mid-1960s. In 1967, Eric Sevareid, a CBS news figure, did two lengthy interviews with Hoffer that were a national sensation. By then, the man who had such disdain and suspicion for the intellectual elite had accepted an adjunct teaching position at Berkeley.

But he remained by nature an outsider. He was at Berkeley at a volatile time, like our own, of occupation and protest. Hoffer had little sympathy for student disruptors:

It is much easier to be a rebel than a hard-working student. . . . It is also much easier to be a hero or a martyr than to strive day in day out mastering knowledge and acquiring new skills.

One of the key and enduring insights of The True Believer is that frustration is the fuel of mass movements. Frustration, though, doesn’t arise solely from bleak material conditions. Hoffer argued, “Our frustration is greater when we have much and want more than when we have nothing and want some.”He points out in the years leading up to both the French and Russian Revolutions, life had in fact been gradually improving for the masses. He concludes, “The intensity of discontent seems to be in inverse proportion to the distance from the object fervently desired.”I arrived as a freshman at the Yale campus when I was 25 years old and had just finished eight years in the Air Force. Like Hoffer, I was an outsider in an elite institution, and his observations about the frustrated are on target. I recall being stunned at how status anxiety pervaded the campus.

At first, I thought, “You’ve already made it, what are you so stressed out about?” But these students—many of whom will never worry about money—couldn’t relax. The competition to “make it” didn’t end with getting into Yale; it only intensified.

Hoffer’s conception of frustration highlights that if your conditions improve, but not as much or as quickly as you’d like, you will be vulnerable to recruitment by causes that promise to make your dreams come true. He wrote:

The frustrated, oppressed by their shortcomings, blame their failure on existing restraints. Actually their innermost desire is for an end to the “free for all.” They want to eliminate free competition and the ruthless testing to which the individual is continually subjected in a free society.

Think how on the mark this is in a world in which there is a powerful movement to literally eliminate standardized testing measuring ability and knowledge—a movement I believe is to the detriment of society.

Here’s Hoffer, on the nature of the masses:

According to The True Believer, extreme mass movements depend not so much on a specific ideology, but on a shared hatred for the present and a yearning for a vaguely defined utopian future. This means that the strongest mass movements are inevitably going to be the ones that are the best at not delivering the goods. Any movement that actually advances the interests of its frustrated supporters will make them less frustrated. Hence, they’ll stop being members.

In a passage in The True Believer that is reminiscent of today’s idea of the “horseshoe theory”—that is, political extremes have more in common with one another than with moderates—Hoffer wrote, “When people are ripe for a mass movement, they are usually ripe for any movement. . . . In pre–Hitlerian Germany, it was often a toss-up whether a restless youth would join the Communists or the Nazis.” One of his most famous aphorisms is this:

Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all unifying agents. . . . Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a god, but never without belief in a devil.

Today we see the frustrated on both sides of the political spectrum. Hoffer presciently worried that “automation” might drastically reduce the kinds of good-paying union jobs that had given him a decent life. Bethell quotes him saying that workers without work might become “a dangerously volatile element in a totally new kind of American society,” one no longer shaped by “the masses” but by the elites.

Here’s Hoffer on the “revolt of the elites”:

Which brings us to the rise of Donald Trump, because Hoffer foresaw him, too. Many think that it is the appearance of a compelling, charismatic leader who galvanizes a mass movement. But not Hoffer. He explains, “There has to be an eagerness to follow and obey, and an intense dissatisfaction with things as they are, before movement and leader can make their appearance.”

When those conditions are in place, a certain kind of figure can then arrive. Perhaps he sounds familiar:

He articulates and justifies the resentment dammed up in the souls of the frustrated. He kindles the vision of a breathtaking future so as to justify the sacrifice of a transitory present. . .

What are the talents requisite for such a performance? Exceptional intelligence, noble character, and originality seem neither indispensable nor perhaps desirable. The main requirements seem to be: audacity and a joy in defiance; an iron will; a fanatical conviction that he is in possession of the one and only truth; faith in his destiny and luck; a capacity for passionate hatred; contempt for the present; a cunning estimate of human nature; a delight in symbols (spectacles and ceremonials); unbounded brazenness which finds expression in a disregard of consistency and fairness. . . ”

There’s more, but you get the picture.

In 1970, Bethell writes, Hoffer announced his retirement from public life. Hoffer described himself as “very tired, very spent.” He said, “I’m going to crawl back into my hole where I started. I don’t want to be a public person. . . ”

He became debilitated by emphysema, but his mind remained sharp until the end. He died in 1983 at age—well, 80 is a nice, round number. His papers and his 3 × 5 cards went to the archives of the Hoover Institution at Stanford.

Bethell writes this epitaph:

“Hoffer was above all an original thinker and an outstanding writer. It is a precious combination. . . . [H]e never followed any intellectual fashion. He was free of the practical pressures that steer so many people of an intellectual disposition into conventional channels of thought. He lay beyond the peer pressure, grant-hunting, and cultural intimidation that stultify much of the academic world today. . . ”

“He had the courage to stand alone.”

Rob Henderson is the best-selling author of Troubled: A Memoir of Family, Foster Care, and Social Class. He earned a BS from Yale in 2018 and a PhD in psychology from the University of Cambridge in 2022. You can follow him on Substack here.

@EvRe!

You are quite correct that Trump did not start the movement which he came to lead, but I would argue that he also came carrying many of the perspectives which he came to voice on behalf of the American people. His sincerity and honesty were important aspects of his political image, but I don’t think he was converted to his position on these topics by his conversations with the American people who have suffered under the heal of the Uniparty elites, but rather that he was emboldened by them to take up the gauntlet and act as the champion to the cause on which he has spoken many times over the years.

I also think that as the people needed Trump to act as their leader, Trump needed the support of the people to actually be that leader, and that they were each, in large ways and small, always aligned towards a symbiotic objective which has coalesced into the MAGA movement. I think that this is why Trump has been so resilient, even as this battle for America has been quite harmful to him and those he holds dear. I also think that this is why Americans have continued to flock to his support in ever larger numbers as they identify with his heartfelt America-first outlook.

@EvRe1 I agree. In fact, at the time, I was an avid follower of a constantly updated pro-Israel news blog, something like Israpundit, entitled, “Jews for Sarah”(Palin). McCain wasn’t the one on the ticket I supported.

I do not agree that Trump started a mass movement.

There already was great unhappiness in the Rust Belt and in rural America, as well as in all towns that once had good middle class factory jobs through which one could raise a family, but those factories were now gone. All the people in all these places in America felt they were lied to repeatedly by every Presidential candidate who made promises and never kept them. They felt like no one was listening. The Tea Party started under Obama. They were targeted by the IRS.

When Trump decided to run, he went to all these places. He actually listened to the people. The people would not have given him another thought had he just gone there to give a speech and then left. He actually spent time to listen to people all over the country. And he understood what they were all saying, since many of them were saying the same thing. He got it.

Then he campaigned on the message to protect American jobs, to close the border, to improve the economy so everyone could get work, and to get out of forever wars.

As the people felt he had listened, they became more interested in him. They found that he was approachable on social media. They also found he didn’t care about political correctness: HE SPOKE THE TRUTH even if it hurt someone’s feelings. They felt never before had a politician actually taken the risk to speak the truth to his or her supporters.

I, myself was doubtful about Trump when his campaign began. Then I saw that he won every primary. I still had some doubts about him, largely due to media stereotypes of him, but I had been very impressed by how successful he had been as a conservative and a really honest one.

I read Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance, that year, and I truly understood how our countrymen and women had suffered since the outsourcing of all our good manufacturing jobs. It’s hard to have an economic recovery if a country is dependent only on financial services, high tech, and service jobs like waitressing. I realized our country had been economically hollowed out by NAFTA (Clinton), surveillance by government robbed Americans of privacy of communications (Bush Jr. Patriot Act and DHS) and the surveillance directed at conservatives (Obama).

So Trump became the candidate he is because he listened to a movement which had begun with the Tea Party Movement under Obama.

Trump wasn’t some guy who mass hypnotized his followers and created a cult, like Hillary thinks he was. It just shows how completely ignorant she is about Americans if she indeed believes that. Certainly it is also contemptuous and denigrating to Americans to even suggest that.

Trump listened. He respected all the men and women Hillary called “the basket of deplorables.” The movement had already begun without him. He just happened to listen to the little guy, and no previous President ever had before.

I wonder if Hoffer was inspired by “The Black Legion” (1937) starring Humphrey Bogart.

https://silverscreenclassicsblog.wordpress.com/2018/06/30/the-black-legion-1937-a-warning-against-fascism-and-bigotry/