Nearly 40 years ago, a University of Chicago professor warned that higher education was closing Americans’ minds. Today, he could be called the grandfather of our culture wars.

By THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS, FREE PRESS MAR 30

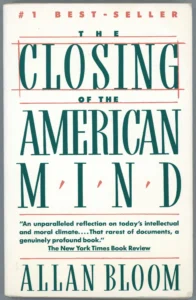

The Closing of the American Mind is Allan Bloom’s 1987 cri de coeur about the collapse of higher education—and young people set adrift intellectually and morally. It is a strange and surprising book written by an eccentric and surprising man. A professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago, Bloom was definitely a snob, sometimes a crank, surely a sexist.

Yet his book’s title struck a note so catchy and compelling it continues to spawn a small industry of volumes that examine and lament some aspect of American life. More than three decades after publication, its cultural influence endures, its obsessions and concerns (most of them, at least) ever more prescient. You could say Bloom is the grandfather of our culture wars.

The book that made him unexpectedly rich and famous elaborated on complaints he’d expressed for years about what had gone wrong with universities and their students. Its subtitle is, after all: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students. In our own day, the campus trends Bloom described have only gotten worse and, as he warned, seeped into society at large, corroding the institutions that support an open society in the first place.

As the 2020s got underway, like many people, especially those working in media and academia, I felt something essential was shrinking. The ability to freely express oneself about the issues of the day—on which reasonable people could genuinely disagree—had become increasingly fraught. As Bloom had described decades earlier, the pressure to advertise fealty to a set of dogmatic beliefs had become ever more intense.

There were many alarming instances. But the catalyst for me was when James Bennet, The New York Times’s editorial page editor, was scapegoated in 2020 for the thought crime of publishing a conservative U.S. senator’s op-ed calling for the military to control rioting and looting. Some Times staff members made the specious argument that the op-ed put black reporters covering the riots “in danger.” Bennet’s forced departure, in part on such safety grounds, showed how campus concerns had migrated to the workplace.

Shocked by this and other events, four friends and I drafted an open letter in defense of equal treatment and free speech.

The “Harper’s Letter,” as it became known, noted the “new set of moral attitudes and political commitments that tend to weaken our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favor of ideological conformity.” The 153 signatories warned that “The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted.”

Our letter received an explosive response, just as Bloom’s book had decades earlier.

Saul Bellow, the Nobel laureate in literature, made The Closing of the American Mind possible. He and Bloom were like-minded friends and colleagues at the University of Chicago’s elite graduate program, the Committee on Social Thought. In 1982, Bloom published an article in National Review about the failings of higher education. Bellow prodded him to turn it into a book.

They were each sons of the Midwest, promising boys of the Jewish middle class who enrolled as teenagers at the University of Chicago, and then ascended to the most rarefied of intellectual heights.

Bloom, born in 1930, was brilliant, awkward, striving. A smoker, a pacer—and a semi-closeted gay man. After he achieved fame and fortune from the runaway success of The Closing of the American Mind, which spent months on the New York Times bestseller list, the journalist James Atlas went to Chicago to profile Bloom for the Times. In the piece, Atlas repeated a joke by another philosopher that the character “Allan Bloom,” and his book, might just be a novel written by Saul Bellow.

Saul Bellow, the Nobel laureate in literature, pictured here in 1976 after it was announced that he’d won the prize, made Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind possible. (via Getty Images)

In The Closing of the American Mind, Bloom begins with the observation that “almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative.” Instead of being set on a challenging course through the humanities to discover enduring truths, Bloom continues, these students are further indoctrinated to believe that searching for truths is futile because they don’t exist.

Bloom saw that American students, in the name of openness, are steeped in a potent and paradoxical relativism that actually closes off the intellect to enduring standards and a genuine grappling with what makes “the good life.” Such grappling is necessary, he asserts, because some things really are better than others. (As Bloom writes: “The United States is one of the highest and most extreme achievements of the rational quest for the good life.”)

And yet Bloom acknowledged America’s many failings, especially regarding race. Making the case for the study of our founding documents, he wrote that Martin Luther King and his cohort of civil rights leaders could rightly “charge whites not only with the most monstrous injustices but also with contradicting their own most sacred principles.” These black leaders, who “relied on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. . . were the true Americans in demanding the equality that belongs to them as human beings by natural and political right.”

Bloom was teaching at Cornell in 1969 when radical black students toting rifles fired shots into the engineering building and seized control of the student union. He repeatedly invokes this episode—it was a destabilizing event for him—especially for what he saw as the mewling response of campus officials.

In The Closing of the American Mind, he acknowledges the radicals’ “very understandable emphasis on self-respect and refusal to beg for acceptance.” But his philosophical concern about such movements was their turning away from universal rights, to be replaced by a struggle for group identity and power.

High-minded tolerance that fails to make judgments is not just mistaken, Bloom argued, it is a deeper betrayal of the university’s founding purpose. That is, to harness tradition, the best of what has been thought and said, in order to mold young souls—Bloom believed in souls—in pursuit of excellence for its own sake (yes, he believed in that, too).

He argued that higher education, having abandoned this central purpose, has been replaced with vocational training and “a smattering of facts learned about other nations or cultures and a few social science formulas.” As he wrote: “The modern university does its best to knock down every prejudice of its students, yet it replaces them with nothing.” (One could easily argue that today’s universities have replaced that nothing with a smothering ideology.)

This matters profoundly, he wrote of his years teaching at elite institutions: “My sample, whatever its limits, has the advantage of concentrating on those who are most likely to take advantage of a liberal education and to have the greatest moral and intellectual effect on the nation.”

Bloom could be self-contradictory and hypocritical. Not every insight in his book holds up. It is hard, for example, to take seriously his obsessive contempt for rock music, or to see his fear of Mick Jagger “tarting it up on stage” as anything other than hysteria.

He also didn’t hide his antipathy for feminism, or women in general. However objectionable we find this, he did anticipate the discourse around “toxic” masculinity: “The souls of men—their ambitious, warlike, protective, possessive character—must be dismantled in order to liberate women from their domination.”

When he turned in his manuscript, Bloom’s publisher had few hopes for the book. As James Atlas wrote, “Simon & Schuster’s editorial board was less than enthusiastic. Not only was the topic dry; Bloom was, you’ll pardon the expression, a nobody.”

But Bellow helped bestow credibility on Bloom and sanctified the book with a forward. In it, Bellow agreed with his friend that the university as an oasis of “intellectual freedom where all views were investigated without restriction” was disappearing. The ethic of its replacement, Bellow wrote, can be summed up as: “Tell me where you come from and I will tell you what you are.”

The critical reception of Closing was variously rapturous, dismissive, and appalled. Critics took issue especially with the idea that some foolishness going on at our most exclusive institutions of higher education would have any effect on society at large. For years, the refrain was that whatever the excesses and follies of university life, the real world would inevitably reclaim students and set them straight.

Despite the book’s ample references to Nietzsche, Hegel, and Kant (or possibly because of them), the American public went wild for it. More than a million copies were sold, making this obscure professor a millionaire and a celebrity.

Money suited Bloom and he spent it lavishly, flying to Paris for Lanvin suits, filling his sprawling Chicago flat with tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of hi-fi equipment to blast concertos during his men-only salons, and ordering German sedans on the telephone from his deathbed.

Bloom didn’t have long to enjoy his good fortune. He died five years after the publication of Closing in 1992 at age 62. According to his New York Times obituary, the cause was “peptic ulcer bleeding complicated by liver failure.” A controversial man in life, the manner of his death became another controversy, with rumors swirling that the actual cause was AIDS.

Then, in 2000, at age 85, Bellow published his final novel, Ravelstein, and Bloom really did become a character in a Saul Bellow novel—life and art were no longer imitating each other but had become fully fused. The book was a roman à clef, the main character a philosophy professor named Abe Ravelstein who wrote an unexpected bestseller and was now facing death from AIDS. The story is narrated by Ravelstein’s friend, a writer who says that Ravelstein wrote a “spirited, intelligent, warlike book” that fueled the culture wars. In a kind of epitaph for Bloom, Bellow writes of his character Ravelstein: “It’s no small matter to become rich and famous by saying exactly what you think, to say it in your own words, without compromise.”

The critical reception to Closing was variously rapturous, dismissive, and appalled. (Simon & Schuster)

Bloom laid the groundwork for understanding how campuses have arrived at what we find today: that is, students who believe that all societies, all people, can be categorized as oppressor or oppressed, with the West permanently understood as the former.

The result has been generations of young people who are ignorant and even contemptuous of America and the Enlightenment principles that made it possible, and who are also inculcated into a superficial and blinkered view of the rest of the world.

It has also led to the rise of the diversity, equity, and inclusion bureaucracy, a totalizing entity whose guiding principles The Free Press reported last year are “valued as equal to or even more important than the basic function of the university: the rigorous pursuit of truth.”

Identity politics were in a more nascent form when Bloom was writing, but he warned that the collapse of civic education would result in teaching that “the Constitutional tradition was always corrupt and was constructed as a defense of slavery”—which is a surprisingly accurate summary of The 1619 Project.

One truth we know without a doubt today, which Bloom had to fight to establish in the ’80s, is that what transpires on campus matters profoundly, and it reverberates nationally and even beyond America’s borders.

Bloom described the rise of spineless university officials, afraid of their own students, as apparatchiks who “did not want trouble,” and who displayed “a mixture of cowardice and moralism.” This would help explain today how people chosen for the presidency of three of the most prestigious universities in our country could appear at a congressional hearing on the rise of campus antisemitism and behave as if they were automatons programmed in legalese, unable to convincingly articulate the basic purpose of a university, or their own guiding principles within it.

Here’s Bloom on classical education, from 1987:

In one of his many references to Friedrich Nietzsche, Bloom observed that the nineteenth-century philosopher can guide us to a greater understanding of our own time. “Nietzsche’s new beginning in philosophy starts from the observation that a shared sense of the sacred is the surest way to recognize a culture, and the key to understanding it and all of its facets,” Bloom wrote. “What a people bows before tells us what it is.”

Consider what is viewed as sacred today, especially by our cultural institutions and leaders: diversity (often of the most superficial sort) for its own sake; emotional and psychological “safety” at all costs (“conflict, the condition of creativity for Nietzsche, is for us a cry for therapy”); ideological commitment and overt activism instead of dispassionate truth-seeking.

There can no longer be any doubt about the impact of this stifling, this closing of American minds, or the decisive role elite universities have played in midwifing it into the cultural mainstream. Last year, authors Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott borrowed from Bloom’s title with their own book, The Canceling of the American Mind, about the silencing and intolerance on campus. They note, “It’s especially alarming that cancel culture is concentrated in the most influential universities in the country.”

Bloom saw this coming decades before most were able to. As he wrote, “Today there are many more things unthinkable and unspeakable in universities. . . and little disposition to protect those who have earned the ire of the radical movements.” He noted of the new moral arbiters, “I fear that the most self-righteous of Americans nowadays are precisely those who have most to gain from what they preach.”

Thomas Chatterton Williams is a staff writer at The Atlantic and a non-resident fellow at AEI. He has taught nonfiction writing and the humanities at a number of American colleges. His next book, about the summer of 2020, will be published by Knopf.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.