The Ukrainian resistance owes more to Judaism than might be thought

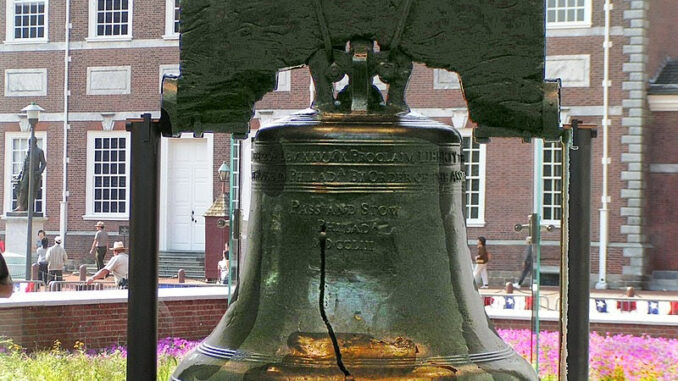

Liberty Bell, Philadelphia

With Ukraine under bombardment by a tyrannical aggressor, this Passover has been an especially resonant time for Jews to be celebrating their freedom as a people.

There are also significant links between Judaism and the resistance by the Ukrainians.

Their desperate battle has shown up as false a core shibboleth of progressive politics. This is the belief that the nation-state is the source of only bad things like nationalism, intolerance and war.

Certainly, Russia’s President Putin illustrates the predatory side of nationalism, justifying his atrocities by insisting that Ukraine isn’t a real nation.

But the astounding determination of the Ukrainians derives from their passionate attachment to their national identity. They fight because they realise that, in defence of their freedom, their nation is everything.

This is where Judaism comes in. For in fusing the people, the religion and the land the Jewish people created the paradigm nation-state.

The tripartite nature of that Jewish identity is unique and so not replicable elsewhere. But in creating the template of the nation-state, the ancient Israelites pioneered what became modern western norms of political power.

True, ancient Israel was a theocracy and was also eventually destroyed by internal divisions. Nevertheless, it developed a concept of governance that was to serve as a template for both Britain and America.

The genius of the Davidic dynasty was that it brought together as one governable nation otherwise disparate and potentially warring tribes.

Even more revolutionary was the ancient Israelites’ concept of limited governance. Their king did not enjoy absolute power. He was constrained from below by the authority vested in priests, prophets and judges, and from above by the belief that the supreme ruler whose laws even the king had to follow was the Almighty himself.

As David Nirenberg writes in his book Anti-Judaism; The History of a Way of Thinking, during the 17th century English civil war Judaism provided the answer to many urgent questions about the relationship between scripture, sovereigns and subjects.

Under Oliver Cromwell, some advocated turning parliament into a “sanhedrin or supreme council” patterned on the Biblical high court of the kingdom of Judea.

The lawyer and “Long Parliament” member John Seldon corresponded with rabbis in the hope of using divine commands to buttress parliament’s aim of extending the rule of law and its institutions even over the church and the crown.

In Leviathan, the seventeenth century philosopher Thomas Hobbes argued that God had himself set sharp limits on his own political power. The authority of Moses, wrote Hobbes, was grounded in the consent of the people and their promise voluntarily to obey the divine voice that they believed spoke through him.

In America, the Hebrew Bible is integral to its foundational institutions and laws. The Liberty Bell is engraved with an inscription from Leviticus: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof”.

America’s founding fathers made repeated reference to Biblical sources. The novelist Herman Melville wrote: “Escaped from the house of bondage, Israel of old did not follow after the ways of the Egyptians. To her was given an express dispensation; to her were given new things under the sun. And we Americans are the peculiar chosen people — the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of the liberties of the world”.

Many non-Jews, however, don’t realise that the Jews are a people with an ancient nation at all. The key difference between people and a people often fails to be acknowledged, particularly among those hostile to Israel’s existence.

Such opponents accuse Zionists of having claimed that Palestine was given to the Jews as “a land without people for a people without a land” — falsely, it’s said, because there were people living there and those people were Arabs.

But this is a misquotation of what was actually said by the 19th century Scottish clergyman, Dr Alexander Keith. He urged Christians to help the Jews who were “a people without a country” to return to “a country without a people”.

The indefinite article was crucial. People may live everywhere. But the claim to rule a piece of territory can only legitimately be made by a people whose particular collective identity is defined within its borders. And in pre-Israel Palestine, whose Arab residents had no such particular collective identity, that legitimate claim was made by the Jewish people alone.

Palestinian Arabs go to enormous lengths to deny this by asserting the falsehood that they and not the Jews are the indigenous people of the land. They write the Jewish people out of their own national story — which they try to conceal by stealing or trashing the archaeological evidence of that ancient kingdom that is constantly being excavated in Jerusalem and elsewhere.

The west abounds with people who disdain the nation-state, are hostile to Israel and believe that, like all religions, Judaism embodies obscurantism, authoritarianism and repression.

It’s ironic, therefore, that so many of them also support the Ukrainian resistance — which owes so much to Judaism, the foundational creed of political freedom.

Excellent & informative.