By Peter Zeihan

Last week the American ambassador to China, Terry Branstad, attempted to publish an op-ed with his assessment of American-Chinese relations. The Chinese Communist Part summarily squashed it, banning the op-ed in all Chinese publications. This Monday, September 14, Branstad submitted his resignation from his post. (He will continue to serve in a caretaker capacity until his as-yet-unnamed replacement can step in in October.)

I hardly have the ambassador’s ear on this topic, but it is fairly clear from the op-ed that Branstad sees no hope for an improvement in the bilateral relationship and that the fault lies with Beijing. The op-ed neither has the tone of someone who is mourning what could have been, or someone ready for a fight. Instead it sounds like someone who after years–decades–of engagement is admitting the obvious: relations are not working and have not been working for sometime.

Chinese-American relations have always been complicated, but they’ve been substantially less sunshiny and rosy in recent years. Differences over trade and finance and bank policy and human rights and navigation and a dozen other things all, independently, would have been enough to inject severe challenge into any relationship. But the simple overriding fact is the two countries have been strategically diverging for some time.

It comes down to demographics, security, trade, and America’s role in the world:

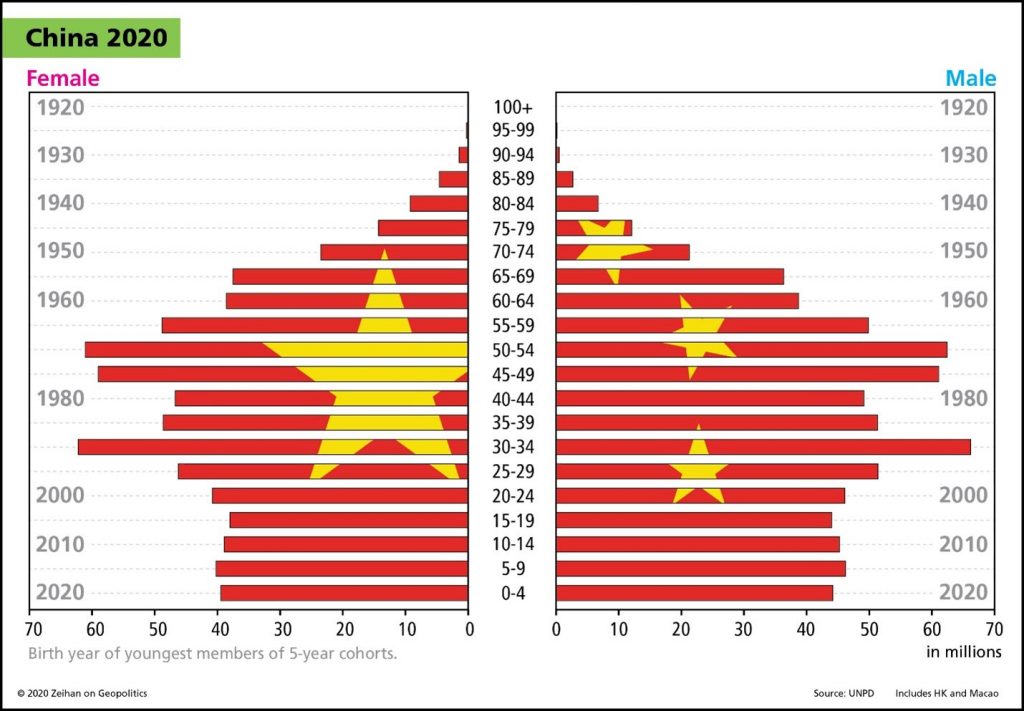

Between rapid urbanization and the One Child Policy, birth rates in China plunged below replacement rates decades ago. The only thing preventing broad-scale population collapse is improved health care among China’s older cohorts which has extended the average Chinese citizen’s lifespan. Demographically speaking, that’s a bit of a starvation diet. Within the decade that demographic dividend will be spent, and China’s population will begin a harsh decline. The most reasonable estimates project a China with half its population in 2100 compared to 2020.

That’s hardly the worst of it–or the part that will be felt first. The 2100 projection ignores the economic effects of today’s young (already numerically gutted) generation. Without sufficient young people, nothing about today’s China is sustainable. The young generation are the people who do work, buy goods, staff the army, and care for the old.

With the younger generation numerically incapable of forming a broad-based consumption-led economy, China has no choice but to lean on exports to power their system. China faces two issues here.

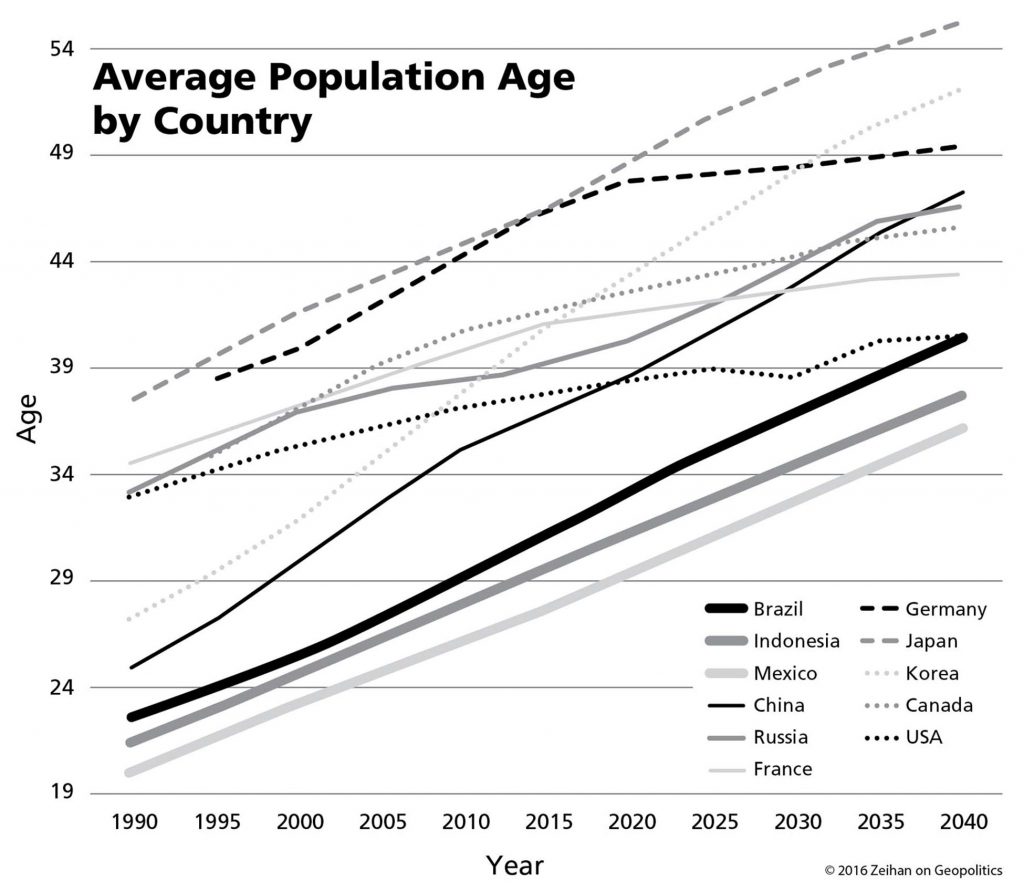

First, like all export-led systems, China relies upon others to consume, and China is hardly the only country suffering from a rapidly aging population.

Within the next decade, enough countries–ranging from the United Kingdom to Brazil to Poland to Chile–will age out of the “consuming” cohort to make the very concept of an export-led economy impossible.

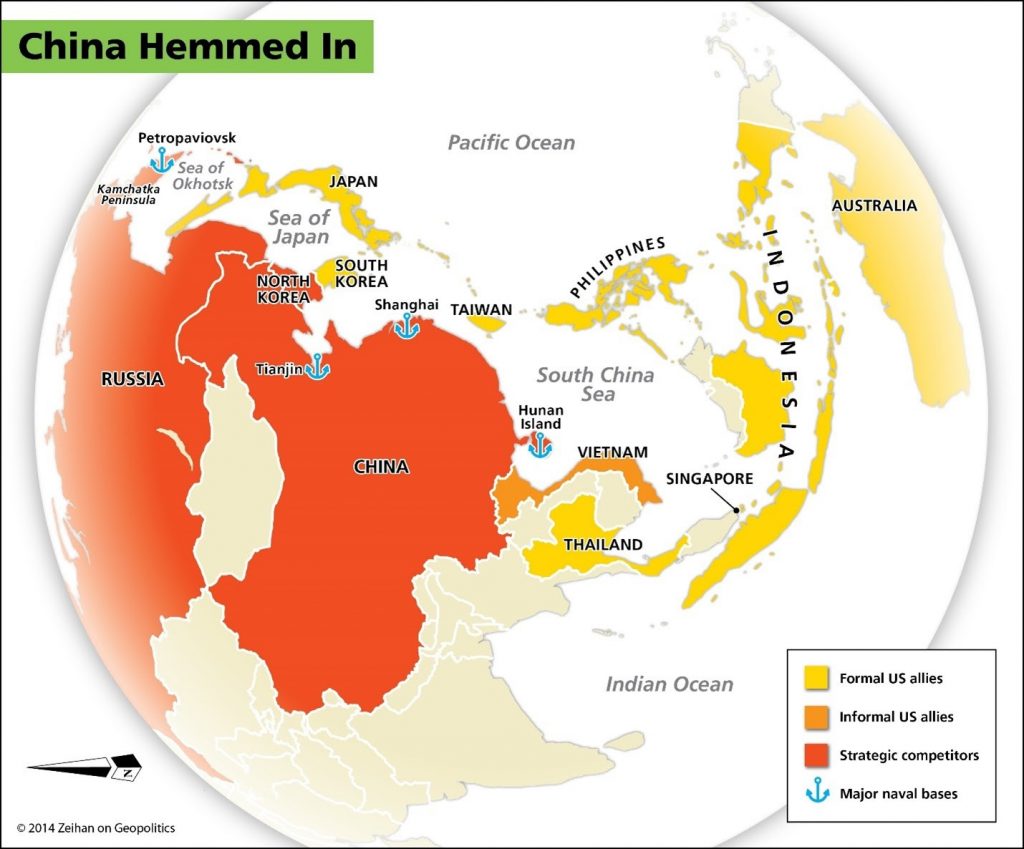

Second, China’s dependence upon imported raw materials and exported finished goods requires physical access. Historically speaking, countries have only been able to enjoy such access if they can militarily secure it themselves. China’s navy may have a lot of vessels, but only a tenth of them have the capacity to sail more than 1000 miles from port. Even that assumes they face no challenge. China’s primary energy supplies are five times that distance. China’s merchandise customers are even further away.

Strategically, China is in a box. The Chinese have only been a global trading power when the countries of the First Island Chain – Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore – have been forced by a greater power to be on the same side as China. That has only occurred once. Today. Under the American-led global Order. If the American goal is truly to destroy China, all the Americans have to do is go home.

Without the Americans negating China’s problematic regional geography and so empowering it on the global stage, China simply lacks the military heft to impose its will on Australia, much less India or Saudi Arabia or Brazil or Germany or the United States–all countries China needs access to if it is to maintain its position.

Which leads us to the most galling, inconvenient truth for the Chinese nation. Everything about its modern history – the defeat of the Japanese, national unification and consolidation under Mao, the turning of the tide against the Soviet Union, its bursting onto the global scene as a major economic player–none of it would have happened without American strategic sponsorship. None of it is sustainable without ongoing American involvement. And the Americans are simply done. With China. With the world. With all of it.

And so, China begins its rage against the dying of the light.

Which brings us back to Branstad. Managing relations between an administration as egocentric as Trump’s and a country as egocentric as China would have been a tough job regardless, but doing so during a period when America is disengaging and China is grappling with the consequences of that disengagement was probably always going to be a thankless task. Yet if anyone was going to eke out any crumbs of success, it was going to be Branstad.

Branstad was no neophyte. First elected governor of Iowa at the tender age of 36, he went on to serve six terms, making him the longest-serving governor in American history. Unlike senators and real estate marketing magnates, governors actually have to deal with people, manage things and establish compromises. In a word, governors…govern.

Branstad, is particularly well-known among the non-Twitter side of American politics for his educational reforms which have consistently put Iowan students at or near the top of most measures. (Full disclosure: I’m from Iowa, was a student there during Branstad’s first, second and third terms, and worked for the Iowa legislature during his fourth.)

Branstad was no hawk. He has known Chairman Xi in a personal capacity since their first meeting back in 1985 when Xi visited Iowa as part of an agricultural delegation. Branstad and Xi have both often commented on their friendship, a friendship grounded in their respective polities’ interactions: Iowa is America’s largest pork producing state, and China is the world’s most enthusiastic pork consumer.

Branstad was no dove. He was one of Trump’s first appointees (and, incidentally, one widely supported on both sides of the American political aisle). His connection to Xi gave Team Trump excellent access within Beijing when pushing on hard-knuckle issues related to trade or intellectual property or navigation rights or Hong Kong.

Branstad was not simply the very best ambassador America had to offer as envoy to Beijing, he may well have been the only person who could have salvaged the American-Chinese relationship these past few years, no matter who sat in the White House.

The question, of course, is what is next?

On the American side things will get harsher, no matter what occurs with national elections in November.

It is impossible to think someone as pragmatic and proper as Branstad would have released the op-ed without President Trump’s personal knowledge and green lighting. After all, the letter has already been endorsed by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and posted on the State Department’s website for all to read.

At its core, Branstad’s op-ed lays bare something that wasn’t exactly a well-hidden secret: that Chairman Xi has been–personally, directly, intentionally and repeatedly–lying to the Trump administration for years on issues both economic and strategic. It stretches the imagination to think that with the cat not so much out of the bag as prancing on the countertop that Trump will treat Xi as anything less than something who has tried to make him look the fool. Cue your imagination for possible retaliations.

Nor would a Biden-Harris administration treat China much better. For the past two years, Biden has been far more critical of China on issues economic, cultural, trade, military, and strategic than anything that’s ever come out of Trump’s Twitter account, going so far as to personally and explicitly label Xi a “thug”. As a former attorney general (aka friend-of-cops), Kamala Harris’ diction regarding Xi has been somewhat less…polite.

Branstad’s op-ed is not a condemnation of a recent Chinese policy shift, but instead an admission that relations are simply impossible unless and until there is a Chinese policy shift.

Realizing that their future likely holds strategic, economic and national oblivion, the Chinese Communist Party–led and personified by Chairman Xi Jinping–has degenerated China into a sort of nationalist fascism that brooks no internal challenge whether racial or political or cultural. One that denies any external influence aside from foreign money that helps employ Chinese citizenry (which in turn bolsters the CCP’s political legitimacy).

It has already become so intense as to border on the comical. China has already closed up to the point that domestic media coverage of Disney’s new theatrical release of Mulan–meant to be a celebration of Chinese culture–is now banned in China because outsiders are lambasting Disney for kowtowing to Beijing.

It isn’t that things that have been in the news ranging from Huawei to Hong Kong to Xinjiang don’t matter–they do–but instead that all of them are symptoms of much deeper problems that the CCP simply lacks capacity to address. Summed up, the CCP and Chairman Xi are desperate. And if we really are approaching China’s witching hour, then all the normal niceties of diplomacy and global trade simply aren’t as important as they once were. Xi sees it as high time to lock down everything and hunker down for the long haul. Foreigners be damned.

And forewarned.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.