Reading ‘American Pastoral’ in the wake of October 7

By

AP Photo/Richard Drew, file

The historical conundrum of the Jewish people has no clear parallel in the long chronicle of civilizations that have come and gone, and those that have survived and prevailed, in humankind’s vast history. Consider other ancient, preexisting non-Islamic tribes in the Middle East. The Samaritans today number fewer than 1,000 living individuals. The Copts of Egypt are under severe pressure. The Yazidi, subject to centuries of forced conversions to Islam and more recently massacred and sold into sexual slavery by ISIS, continue to hold on in profoundly diminished form, predominantly in Iraq. Other tribal or ethnic groups, including the Philistines, Amorites, Edomites, Lydians, Moabites, and Hittites, are long extinct. As Carl Sagan once put it in a broader context, “Extinction is the rule. Survival is the exception.”

The Jewish people constitute one of those rare exceptions. They have managed not only to survive but to thrive, even after half of the global Jewish population was wiped out in the mechanized mass murder of the Shoah. Today, for the first time in modern history, Jews have their own nation in Israel, and the Diaspora has achieved a phenomenal level of success far out of proportion to its numbers, in the U.S., Canada, Western Europe, and throughout the world.

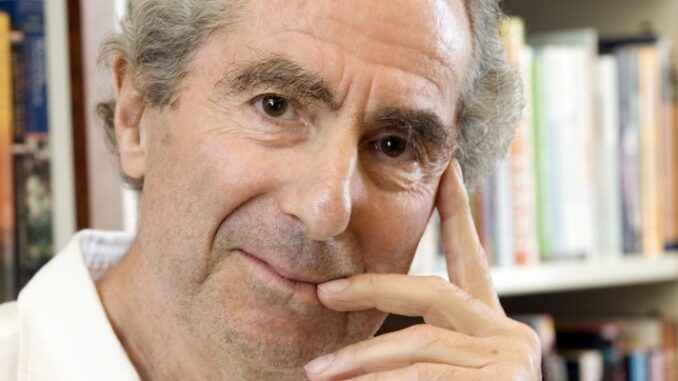

Yet, as throughout its 3,000-year history, that success is ever contingent, ever threatened, ever insecure, frequently reviled, and always afraid to proclaim in a full-throated voice its Jewish pride and to speak explicitly about the Jewish values and traditions that have helped to engender its many achievements. We can see this in the work of the longest-enduring and perhaps final voice of the American-Jewish literary vogue that gripped the country in the 1950s and 1960s. Philip Roth, descended from Ukrainian Jews who made their way to New Jersey, spent his life (born 1933, died 2018) in a tortured and tortuous relationship with his own Judaism and Jewishness. In that sense, he was a model of the costs and also the benefits of displacement, and his best work embodies and transcends the existential dilemma that gripped him and so many Jews of his time.

In perhaps his finest novel, American Pastoral, he created a wrenching and indelible portrait of the American Jewish experience of assimilation, with a bleakly pessimistic ending that illuminated the darker corners of the Jewish entrapment between the left-wing anti-colonialist and right-wing racist forces that now work together to tell Jews, in effect, When you are in Europe, go to Palestine. When you are in Palestine, go back to Europe. If you stay where you are, hide your mezuzahs and your Stars of David and your tefillin if you want to be safe. If you leave, don’t by any means go to Israel, because then you are a colonialist. You have no home here, you have no home there, and you have no home anywhere.

Seymour Levov, the graceful, athletic, kind, and tragic subject of American Pastoral, exemplifies the contingent dilemma of the modern American Jew. Born during the Depression, he becomes the glowing idol of his fellow Jewish students at a New Jersey high school, among whose number is Roth’s long-time fictional alter ego Nathan Zuckerman. Seymour excels at high-school sports and, just as important, has blond hair and blue eyes and so does not look like a stereotypical Jew. He is the model of assimilation, which is, at its furthest reaches, the Jewish suppression of one’s own Jewishness. The purpose of this suppression? To, at best, fit comfortably into the Gentile world and, at worst, not to be persecuted and murdered.

Would Nathan Zuckerman and his fellow Newark students have admired Levov—who “starred as end in football, center in basketball, and first baseman in baseball”—quite so much if his batting average were even higher and his receiving yards even greater but he looked more like Philip Roth himself?

Unlike Ms. Velitskaya, I considered Phillip Roth to have been a complete dirtbag., In his novels he portrayed sympathetically men who lied to their numerous sexual partners, misleading each to think that she was the only one in his life. He ridiculed Israel and denounced Zionism. In his novels, there are only men who are promiscuous with numerous sexual partners, never once a couple in a serious, mutually committed relationship in which there is love as well as sex. His heroes always aspire to be accepted in elite, mainly non-Jewish social circles, and to leave their Jewish roots behind them.Jewish parents are ridiculed as overprotective and even (physically) constipated. In effect, Roth seeks to make sex a false religion as a replacement for Judaism. That he was given a Nobel Prize for Literature is a disgrace to the Nobel foundation and its Scandavian government sponsors.