By Fransisco Gil-White, MANAGEMENT OF REALITY 16 February 2024

Assyrians torturing prisoners of war. (Credit: New York Public Library)

In Part 1 of this series I mentioned Sargon of Akkad—a man with no equal—who led the ancient Semitic lower classes in revolution against their Sumerian rulers and established the Akkadian Empire 4,300 years ago.

This event—Sargon’s revolution—established a remarkably stable legal and political culture centered on the ideals of ethics, justice, and the protection of the vulnerable that, over the next 4,300 years, would liberate humans by the hundreds of millions. (Still at it…)

It is this remarkable culture, this ideology, that I am calling semitism.

In Part 2, which follows below, I’ll give you a sense for the literally epic impact of semitism on world history. And then, in Part 3, I will explain how semitism transformed the West and is today becoming aware of itself, gathering strength for one last great fight for liberty.

(I apologize for the Tolkienian overtones, but it’s… all true!).

That’s ‘semitic’ with a lower case ‘s’ instead of the capitalized ‘Semitic.’ I am referencing ideology rather than a linguistic community.

Of course, there is a relationship here between language and ideology. It was speakers of Semitic languages who first established this ideology, and it was Speakers of Semitic languages who preserved and developed it (that’s one reason I am calling it ‘semitism’). But speakers of non-Semitic languages may of course adopt this ideology—and over the centuries many have. In three important epochs, the peoples of Babylonia were ruled by non-Semitic speakers who lovingly ensured the continuity of semitism in that civilization.

Now, since the pursuit of compassion, ethics, tolerance, justice, and equality is what I call semitism, then it follows, staying within the strictest etymological logic, that the totalitarian quest to make us all slaves should be called antisemitism.

Well guess what? We already speak like that. The German Nazis meant to destroy democracy and make every one of us (including the Germans) slaves, and we do call them antisemites. Moreover, in perfect agreement with the distinctions I am pushing, what the German Nazis hated was not the Semites, but semitism.

I can prove that. All it takes is a short detour to consider the Nazi relationship to the Arabs. Because although Arabs speak a Semitic language, the Nazis were quite attracted to them. And Adolf Hitler himself was besotted with the Arab religion, Islam.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister of armaments, wrote about that after the war in his contrite memoir, penned in prison. Hitler, Speer said, loved Islam because it was “a religion that believed in spreading the faith by the sword and subjugating all nations to that faith.” Had the Muslims conquered Europe in the Middle Ages, instead of “[getting] driven back at the Battle of Tours [Poitiers],” Hitler believed, then “Islamized Germans could have stood at the head of the Mohammedan Empire.”

That’s interesting. It means that the German-supremacist Adolf Hitler would have liked the Muslim Arabs to militarily defeat the Medieval Germans! And just so that Germans could inherit Islam! This betrays a rather pronounced love of the Mohammedan religion.

And he would harp on this theme often.

“Hitler usually concluded this historical speculation by remarking: ‘You see, it’s been our misfortune to have the wrong religion. … The Mohammedan religion … would have been much more compatible to us than Christianity.’ ”1

Consistent with all that, before and during WWII, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis happily forged important alliances with leaders all over the Muslim Arab world, and these Muslim Arab leaders and their movements reciprocated Hitler’s love of Islam with open admiration for the German Nazis.

It all fits, because, despite all the talk of the ‘Abrahamic faiths,’ it is Judaism—and not Islam—that has come to our day as the human vehicle expressing the ideals of Mesopotamian semitism. Islam is something else entirely and has no real relationship to Judaism. Any claim to the contrary is a simple fraud—a fraud that is foundational to the genesis of Islam.

As Hitler correctly recognized, Islam expresses ideals either identical or adjacent, functionally and politically, to those of the German Nazis. So, of course, Hitler had no quarrel with Islam—to the contrary. His quarrel was with the human vehicle of semitism in the West, the Jews, and with the most sophisticated modern expression of semitism, which is Western democracy. That’s what the Nazis hated.

I claim my terms of art, and the model they support, nicely fit other centuries too. The way to test that is to consult the rest of our history. For if this really fits as a general model, then past haters of Jews should also have been totalitarians interested in enslaving every one of us (not just in killing Jews). And they are! The jihadists, the German Nazis, the Russian boyars, the ‘Holy’ Inquisitors, the ancient Roman aristocrats, and the ancient Greco-Macedonian aristocrats, all of whom committed genocide against the Jews, were all busy making slaves of everyone else too. They were enemies of everyone’s liberty.

Antisemites!

Of course, the medieval and ancient totalitarian oppressors of Westerners have been apologized for in our schools with the claim that slavery and oppression were universal in the past because, allegedly, before modern times, the condition of ignorance on matters ethical was suffered by all. But that story is false.

They’ve sold us on this story because we learn almost nothing about ancient Mesopotamia in school, so we’ve accepted the ethnocentric lie that the entire ancient world was as awful as the Greco-Romans, whom we were schooled into accepting as our main heritage. But some ancient societies, by stark contrast to the Greco-Romans, were liberal. Yes, there was some slavery in Mesopotamia too, but those slaves were relatively few, and they were treated as persons, not animals (they didn’t have freedom, but they did have important legal rights, and they were not treated with cruelty).2 In their values and civilizational goals, Babylonian societies were remarkably similar to our modern, democratic Western States.

That similarity is no coincidence. Mesopotamian semitism—also our heritage—has been fighting for everyone’s liberty from the earliest civilization, starting with Sumer. The defenders of semitism fought the ancient Greco-Romans who tried hard to destroy semitism in Mesopotamia. And via the Jews, semitism in the end seduced even the Greco-Romans and their cultural descendants, which is why, at long last, we were able to produce modern Western democracy.

In sum, in this analysis, the struggle between semitism and antisemitism is the engine of our entire political history. And Judeophobia—the specific hatred of Jews (as such)—though it is certainly antisemitism, must be recognized as a special case of it.

Okay, enough about terminology. Now let’s get on with the story.

Yes, Judeophobia is a special case of antisemitism, but for a long time now this special case has been the entire game. That’s because, in the 7th century, Islam, that great antisemitic current, destroyed semitism in Mesopotamia, so the Jews (and their Christian progeny) are all that survives from ancient semitism. Yet the impact of Judeo-Christian thought to liberate all humans has been tremendous. Think only of the weekly day of rest, a blessing the entire planet inherited from the Jewish Sabbath. Or think of democracy, another modern consequence of Judeo-Christian semitism.

Semitism has always been doing this—it has always been fighting for us. To discover that millenarian pattern, we must go back to the beginning: to Mesopotamian antiquity.

In Part 1 I told you about Sargon of Akkad—Sargon the Great—who led the subjugated Semites in Sumer to revolt and with their help established the Akkadian Empire. This got semitism rolling 4,300 years ago. And the Akkadians kept themselves on that roll for a good 200 years.

The Akkadian Empire at its largest. Wikipedia.

But empires fall. The Gutians—who’d already been making trouble—came from the east and imposed themselves.

The scholar Bill T. Arnold explains that in Mesopotamia the “downfall of the Akkadian empire” was interpreted “for well over a millennium” in entirely moral terms. According to a cuneiform Mesopotamian document called the Weidner Chronicle, “Marduk, King of the Gods” sided with the Gutians against the Akkadian king Naram-Sin because the latter had allegedly become oppressive against his own people: “Naram-Sin destroyed the people of Babylon. Twice [Marduk] summoned the Gutian army against him.”3

The archaeological evidence rescues the reputation of Naram-Sin, who appears to have been a good king. But even if the Weidner Chronicle—a religiously propagandistic text uninterested in historical accuracy, and written a great many centuries after Naram-Sin—is unfair to that king, what I am drawing attention to here is a Babylonian tendency to view historical events in moral terms. That’s something that we also find—and in spades—in the Hebrew Bible (Tanach), where God sends enemies to punish kings accused of deviating from ethical governance (see the Book of Kings and the Book of Chronicles).

And this appears to be a very old Babylonian tradition. Consider the manner in which Utu-hengal, who expelled the Gutians after they had ruled for about one hundred years, interpreted his success in the famous Utu-hengal victory stele or Tablet of Utu-hengal:

… Gu[tium], the fanged serpent of the mountain, who acted with violence against the gods, who carried off the kingship of the land of Sumer to the mountain land, who fi[ll]ed the land of Sumer with wickedness, who took away the wife from the one who had a wife, who took away the child from the one who had a child, who put wickedness and evil in the land (of Sumer) — the god Enlil, lord of the foreign lands, commissioned Utu-hegal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters, the king whose utterance cannot be countermanded, to destroy their name.

The moral interpretation—where divine punishment follows unethical treatment of the governed—is impossible to miss: The god Enlil favored Utu-hengal because the Gutians had “filled the land of Sumer with wickedness,” meaning murder, because the Gutians had conquered Akkad by the sword, rape (“took away the wife from the one who had a wife”), and slavery (“took away the child from the one who had a child”). Utu-hengal understood the language of universal human rights: whoever brought murder, rape, and slavery “put wickedness and evil in the land.”

The ‘Neo-Sumerian Empire.’ Image modified from Wikipedia.

Now, historians have chosen to call Utu-hengal, his son in law Ur-Nammu, and Ur-Nammu’s dynastic descendants ‘neo-Sumerians kings.’ I think that label is misleading. Yes, they were ethnically Sumerian, but they were entirely uninterested in recreating the ancien régime political tradition of Sumer. To the contrary, Utu-hengal and Ur-Nammu saw themselves as restorers of the revolutionary Akkadian Empire. They were ideological semites.

And that, in itself, is striking. It means that, by the time the Gutians came along, it no longer mattered whether the people of Babylonia were ruled by Semites or Sumerians because Sargon’s monarchical ideology—extending rights to everyone, and protecting the lower and vulnerable classes—had been thoroughly institutionalized during the two centuries of Akkadian rule and had transformed everybody. Utu-hengal and Ur-Nammu, ethnic Sumerians, were proud defenders of this semitic liberal culture.

To signal the restoration of semitism, Ur-Nammu and his successors adopted the title ‘King of Sumer and Akkad,’ which included the title earlier worn by the Akkadian emperors. And in the prologue to the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known legal code rescued as a text from the mists of time, the king expressed in lofty tones the grand purpose of Akkadian civilization:

“… Ur-Nammu … in accordance with his principles of equity and truth … established equity in the land; he banished the curse, violence, and discord … The orphan was not delivered to the wealthy man; the widow was not delivered to the powerful man; the man of one shekel was not delivered to the man of one mina [= 60 shekels].”

Shulgi, son of Ur-Nammu, considered one of the greatest kings in Mesopotamian history, stated in the text ‘Shulgi, King of Abundance,’ that among his monarchical obligations were the following:

“To let justice never come to an end. To throw evil in the Depths, as if it were a light stone, to let no man make his fellow a hireling.”4

The peoples of the restored Akkadian Empire (the ‘Neo-Sumerian’ Empire of historians) were fortunate to have rulers whose ambition was to be seen by the governed—even by the very weakest (widows and orphans)—as defenders of ethics and justice!

After the ‘neo-Sumerians’ it was ethnic Semites in power again, this time Amorites, during the long Isin-Larsa period about which little is known, when power was fragmented again in local city-States.

Then one Amorite King, Hammurabi, reunified Babylonia. Three hundred years after Shulgi and half a millennium after Sargon, Hammurabi renewed the title of ‘King of Sumer and Akkad’ when he founded the Old Babylonian Empire.

Hammurabi’s Old Babylonian Empire. Image: Wikipedia.

In the prologue to his famous legal code—which would be copied and studied by Mesopotamian scholars for a millennium to come—Hammurabi expressed what he understood to be his monarchical obligation:

“to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; … and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind.”

This is semitism.

Antisemitism, then, seeks to destroy the empire of righteousness (ethics), the protection of the weak, and the well-being of mankind.

Hammurabi’s Amorite dynasty was ejected from Babylonian power when the Hittite King Mursili I came down from Anatolia and raided Babylon. Mursili quickly returned to Anatolia—his campaigns had strained his resources and produced much unrest at home—but not before leaving his Kassite allies in control of Babylonia.

The Kassites were highly successful rulers of Babylonia, the southern region of Mesopotamia, and ruled it longer than anyone else. We don’t know much about them, but everything we do know suggests that the Kassites, who did not speak a Semitic language, became ideological semites. The Kassite kings adopted the title ‘King of Sumer and Akkad,’ kept Akkadian as the official language, and kept also the bureaucratic structures of the Old Babylonian Empire. Such continuity would explain why, long after the Kassites, who themselves ruled for a good four centuries, Hammurabi’s Code continued to be tremendously influential.

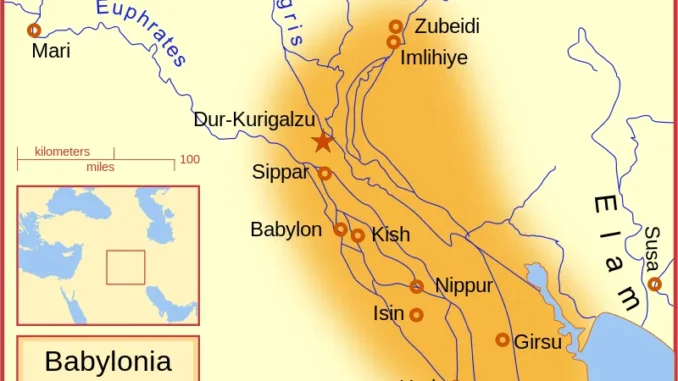

The Kassite Babylonian empire 13th century BCE. Image: Wikipedia.

At long last the Kassite Empire in Babylonia was undone by attacks from the Assyrian Empire to the north and from the Elamites to the east. The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III conquered Babylon in the year 729 BCE.

The encounter between the Kassites and the Assyrians helps us see clearly, once again, that the terms employed here reference ideology, not language or ethnicity. For just as semitism could be adopted by rulers who speak a non-Semitic language, as with the Kassites, so could antisemitism seduce speakers of Semitic languages, such as the Assyrians, who spoke a dialect of Akkadian.

Evil had come to roost. Completely given over to war, slavery, and cruelty, the antisemitic Assyrians were consummate monsters, astonishingly and proudly brutal. Their strategy of control was terrorism, so in their inscriptions the Assyrian kings—quite unlike Sargon, Ur-Nammu, Shulgi, and Hammurabi—celebrated the suffering that they imposed on everyone, boasting of how they ravaged cities, exterminated and exiled entire peoples, tortured innocents, and enslaved the masses.

The Assyrian Empire. Image: Wikipedia.

What Assyriologist Marc van de Mieroop calls “the ideological basis of rule in Assyria” presents some important functional similarities to the later jihadis, so obsessed with totalitarian order. Consider:

- jihadis partition the world into Dar al Islam (the ‘House of Islam’) and Dar al Harb (the ‘House of War’);

- jihadis conceive of those living in Dar al Harb as ‘infidels’ who’ll either join Islam or else be killed or enslaved (a process that, in their conception, brings ‘peace’); and

- jihadis consider that terrorism is a good and proper method both for keeping existing Muslims in line and also for making additional Muslims.

Here’s the Assyrian version of all that:

“The king, as representative of the god Assur, represented order. Wherever he was in control, there was peace, tranquility, and justice, and where he did not rule there was chaos. The king’s duty to bring order to the entire world was the justification for military expansion. This idea pervaded royal rhetoric. All that was foreign was hostile, and all foreigners were like non-human creatures. Images of swamp-rats or bats, lonely, confused, and cowardly, were commonly applied to those outside the king’s control. This message was communicated through a variety of means. Royal inscriptions are the most eloquent to us today, but in Assyrian times they were incomprehensible to the mostly illiterate population. The people were informed through events such as victory parades, and there is evidence that certain campaign accounts were read aloud in the cities.”5

To get a sense for what Assyrian subjects heard when these kingly inscriptions “were read aloud in the cities,” let us consider Ashurnasirpal II, the third king. His idea of ‘order’ was apparently to demand the most oppressive tribute imaginable from the cities he ruled, which caused these cities to rebel. So he punished them. To boast of that punishment, Ashurnasirpal didn’t have the modern tools employed by the Hamas terrorists, who proudly broadcast on social media their gruesome crimes of October 7th, 2023. So this Assyrian king used official inscriptions and had them read aloud to his enslaved subjects:

“I built a pillar over against the city gate and I flayed all the chiefs who had revolted and I covered the pillar with their skins. Some I impaled upon the pillar on stakes and others I bound to stakes round the pillar. I cut the limbs off the officers who had rebelled. Many captives I burned with fire and many I took as living captives. From some I cut off their noses, their ears, and their fingers, of many I put out their eyes. I made one pillar of the living and another of heads and I bound their heads to tree trunks round about the city. Their young men and maidens I consumed with fire. The rest of their warriors I consumed with thirst in the desert of the Euphrates.”

Mordor.

The shadow of death extended over a vast territory, for the Assyrians created the largest empire the world had ever seen.

Many people were cowed, so terrible was Assyrian violence. Yet the Assyrians couldn’t shake their ‘Babylonian Problem,’ as scholars have begun to call it: no matter how much violence the Assyrians directed at Babylon, the Babylonians would revolt again. Again and again.

This was no doubt because, for the Babylonians, who had discovered the secret of cultural tolerance and political freedom, nothing in the Universe could ever make sense again unless the psychopathically insane and bloodthirsty Assyrians were first utterly defeated. It was an existential fight, and it led to the first great ‘World War’ of antiquity (there would be two more).

That world war was won by Nabopolassar, believed to be a Chaldean (again, a Semite), and a man larger than life. It was he who led the oppressed Babylonians to destroy the Assyrian Empire.

Nabopolasar attacked the Assyrian heartland from the south, and the Mede Cyaxares from the East.

After this, Nabopolassar declared himself ‘King of Sumer and Akkad,’ which is to say successor to Sargon, and formed the Neo-Babylonian Empire, restoring the culture of semitism in Mesopotamia. This happened 1,700 years after Sargon, in the year 609 BCE.

To defeat the Assyrians, the Babylonian Nabopolassar had allied himself with Cyaxares, leader of the Medes, an Iranian people (to the northeast) also oppressed by the Assyrians. Following victory over the Assyrians, the Medes created a vast empire that did not, however, dispute Nabopolassar’s right to Babylonia or, indeed, to the rest of Mesopotamia.

The Median and Neo-Babylonian empires. Image: Wikipedia.

The Median and Neo-Babylonian empires. Image: Wikipedia.

But though that alliance held, the destruction of the Assyrian cities by the Medes had caused much shame in Babylonia, homeland of Semitism. The Medes had demolished and burned everything in the Assyrian cities, not even sparing the temples, and they had exterminated the population, including the children.

Nabopolassar was not entirely innocent but the point here is the shame, felt so keenly that later chroniclers in Babylon tried to exonerate Nabopolassar and blame the Medes entirely. Why so much shame? Because within semitism such violence, even against the cruel Assyrian terrorists, was considered a sin. As in the modern West, the Babylonians considered that war—even against terrorists—had to be conducted according to rules of ethics.

The Medes would not long stay so violent, however, as Iranian civilization was undergoing a profound transformation. The vast Median empire was lord over many eastern Iranians who already followed the path of universal peace, brotherhood, and justice preached by the Iranian prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra). In one of the most important religious transformations in history, the Medes—and also their allies, the Persians (another Iranian people)—converted to Zoroastrianism.

Thus it was that when Astyages, Cyaxares’s son, became oppressive, the Median nobles allied with the Persians, led by Cyrus, King of Anshan, who, spearheading a large army of peasants (according to Herodotus), overthrew Astyages in a new revolution. Cyrus—Cyrus the Great—re-founded the Median empire as the Achaemenid Persian Empire (550 BCE).

Soon after that, Cyrus successfully led a gigantic multi-ethnic army to defeat King Croesus of Lydia, an antisemite who had attacked Cyrus’s Western border and begun to enslave his people. And then Cyrus unseated Nabonidus, then ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, who, judging by the alliance that Herodotus alleges he’d established with Croesus, was apparently becoming oppressive too (Cyrus’ propaganda certainly accuses that).

The Achaemenid Persian Empire. Image: Wikipedia.

With the additional conquests of Cyrus’s son Cambyses, the Persian Empire became something never before seen. From Egypt and present-day Turkey (and even a tiny piece of Europe), in the west, to what is now Pakistan, in the east, this empire would encompass the peoples of western Asia and bless them all with a combination of Zoroastrian and semitic ethics.

Cyrus was… the Messiah.

I am not indulging hyperbole—that’s a literal claim. The Book of Isaiah, origin of the Jewish messianic tradition, speaks of an ethical and revolutionary liberator (not a mystical sacrificial victim), and calls Cyrus the Messiah of the Lord: “Thus says the Lord to his Messiah, to Cyrus whom I took by his right hand” (Isa 45:1). He is the only figure to be given this title by Isaiah: the Lord’s Messiah. And he certainly looks the part: Cyrus ‘saved the world’: he brought peace almost to the entire oikoumene (what the Greeks called the ‘Known World’ of city folk).

Under Cyrus and his successors, the Achaemenid Persian Empire became a grand alliance of Semitic and Zoroastrian peoples, united in the common mission of universal peace, brotherhood, and justice.

Semitism, via the Jews and Christians of the West, continues to this day as a powerful force in World History, whereas Zoroastrianism has all but disappeared. Thus, it is attractive for my purposes to see the enduring Zoroastrian legacy primarily as a contribution to the historical stream of Babylonian semitism (with which Zoroastrianism has a deep ideological affinity).

This approach is also supported by other details.

First, though a Zoroastrian, Cyrus governed like a good Semitic king: 1) he incorporated Babylon into his empire and made it one of his capitals; 2) he added ‘King of Sumer and Akkad’ to his titles, thus declaring himself a successor to Sargon; 3) he ensured that the Babylonian Semitic traditions of religion and law continued; and 4) he made Aramaic—a Semitic language that had become the lingua franca of Mesopotamia by this time (much like English is today at a global level)—the official language of the Persian Empire in those regions settled by Semites.

But that’s not all. In Babylon, Cyrus encountered a great many Jews—also Semites—who’d been exiled there some 70 years earlier by King Nebuchadnezzar II (son of Nabopolassar) after an Israelite revolt against Babylon. Cyrus found in the Jewish legal and religious movement the most refined, mature, and sophisticated development of the legal project for peace and justice initiated so long ago by Sargon the Great. And so Cyrus, the Zoroastrian king of kings of Western Asia, the most powerful man who had ever existed, became the great patron of Judaism, a religion founded on the memory of a slave revolt (see Book of Exodus) that expressed—better than any movement before it—the central values of Babylonian semitism

The Jews of that time were proselytizers: they wanted to convert the entire world to Judaism and thus put an end to war and injustice, establishing peace and brotherhood everywhere. According to what is narrated in the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah (included in Tanakh, which is included in the Christian Bible), Cyrus appreciated these Jewish goals, and supported and subsidized the Jewish movement, as did his successors. Thus protected within the Persian Empire, the Jews carried a universal message of love, peace, and justice everywhere they went, becoming—in part through conversion—one of the largest populations of antiquity, spilling outside of the empire to the east, into Asia, and to the west, into the Mediterranean.

In the Mediterranean, just beyond the Western (Aegean) coast of present-day Turkey, which was the westernmost border of the Persian Empire, lay the most accomplished and dangerous antisemites of all: the Greeks.

Looking West from Babylon, the Persians worried about them.Whereas the Babylonian kings had defended an ideology of government anchored on the memory of ancient and more recent revolutions that had shaken the yoke of oppression to establish and restore the pursuit of ethics and justice as a civilizational goal, the Greeks instead anchored their entire identity on the story of an ancient genocide.That’s the story of The Iliad, which no doubt you were made to read in school under the heavily insistent interpretation that this is a wondrous work of art and something entirely to admire. The poetry is perhaps sublime (who am I to judge?), but peel that away and you’ve got the following story: Helen, the beautiful wife of the Spartan king, fell in love with the non-Greek prince Paris, from Troy, and escaped with her lover after a royal Trojan visit to Sparta; in reply, all the ethnic Greek kingdoms together sent their warriors to burn Troy to the ground and exterminate the Trojans. For the ancient Greeks, this genocidal crime was a proud memory and its perpetrators heroes worthy of emulation.And emulate they did. Like the Assyrians, entirely and proudly devoted to war and slavery, the Greeks would go to war every spring, like the farmer to the soil. It had to be thus because the predatory political economy of the Greeks was largely based on pillage, material and human. Once they had defeated an enemy city, the traditional practice was to steal any valuables and execute in cold blood all surviving adult men among the citizens, then take the women and children away as slaves. Any slaves previously held by the defeated city were also war booty, of course.This resulted in a particular social structure. As mentioned in Part 1, a census of the small Athenian empire in the late 4th century counted 21,000 Athenian citizens and 400,000 slaves.

Mordor, again.

The Greeks were sharply aware that sooner or later they would have to destroy Mesopotamian semitism or be destroyed themselves. For semitism was now being promulgated and defended by the most powerful empire ever seen, the Achaemenid Persian Empire, larger even than the Assyrian. And semitism was seeping out of that empire and sneaking itself everywhere, seducing the entire world, threatening to break the chains of the Greek slaves.

In consequence, world war returned to the oikoumene. Or I should say world wars (plural).

First were the two great Greco-Persian wars—wars so gigantic, and so awesome to those who witnessed them, that they gave birth, in the Herodotean reed, to the discipline of History. I consider them together as two episodes of one world war: the multiethnic Persian Empire’s attempt to conquer the Greeks.

That attempt failed: the antisemites in the Greek peninsula successfully resisted.

Amazingly (at least for those following my narrative), that outcome has been celebrated by Western historians as a victory for ‘democracy’ against ‘autocracy’! These historians evidently consider the suffrage of a handful of criminals at the top of Athens as entirely more precious than the copious legal rights extended to everyone in Babylonia and in the rest of the Persian Empire—even to the slaves (who were not so many).

Then came the next world war: the Alexandrian defeat of the Persians, a naked act of plunder and destruction, and the beginning of terrible oppression for Western Asians. Western historians have chosen to celebrate this too. Alexander—who is perhaps best compared to someone like Adolf Hitler—is supposed to have been a wonderful guy.

The short-lived Alexandrian Empire. Image: Wikipedia.

According to Plutarch, Alexander the Macedonian (not ‘the Great,’ please…), educated by his tutor, the philosopher Aristotle, was told that, upon conquering Asia, he should treat Asiatics “ ‘like plants or animals.’ ”6 Ever the good pupil, Alexander was fond of burning Asian cities to the ground and crucifying his war prisoners by the thousands (like he did, for example, in Tyre). He celebrated his conquest of the Persian Empire with a great drunken revelry and then set fire to the sacred city of Persepolis—a gem—in its entirety, after which he brought slavery—Greek-style—to the peoples of Western Asia.

Historian Gunther Hölbl considers Alexander “a fanatical autocrat.”7 It fits.

<blockquoteAnti-Semitism or Antisemitism?

by Mitchell Bard

The term “anti-Semite” was coined in Germany in 1879 by Wilhelm Marr in his pamphlet “The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism” to refer to the anti-Jewish manifestations of the period and to give Jew-hatred a more scientific sounding name. According to historian Deborah Lipstadt, instead of using the word “Judenhass” – hatred of Jews – he chose “Antisemitismus” – hatred of the Jewish race. Lipstadt says he wanted an “all-encompassing word: a word that would include Jews who were no longer practicing the religion, Jews who might even have converted – because he also was influenced by the idea that it was in your blood.”

Zack Rothbart noted that “Anti-Semitism” did not appear in the original edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. He quotes from a July 5, 1900, letter from James Murray, the founding editor, to Claude Montefiore, the great-nephew of Moses Montefiore. “He said ‘the material for anti- words was so enormous that much violence had to be employed’ to include them all. ‘Anti-semite and its family were then probably very new in English use, and not thought likely to be more than passing nonce-words,’ Murray added, ‘& hence they did not receive treatment in a separate article. Probably if we had to do that post now, we should have to make Anti-semite a main word, and add ‘hence Anti-semitic, Anti-semitism.’ He also noted, ‘The man in the street would have said Anti-Jewish.’”

“Anti-Semitism” has been accepted and understood to mean hatred of the Jewish people. Dictionaries define the term as: “Theory, action, or practice directed against the Jews” and “Hostility towards Jews as a religious or racial minority group, often accompanied by social, economic and political discrimination.”

Today, there is a debate as to whether the word should be spelled without a hyphen.

Some argue the use of the word “Semitic” is misleading and confusing used in the context of Jew hatred. In its argument for eliminating the hyphen, the ADL noted the word “was first used by a German historian in 1781 to bind together languages of Middle Eastern origin that have some linguistic similarities. The speakers of those languages, however, do not otherwise have shared heritage or history. There is no such thing as a Semitic peoplehood.”

Arabs are “Semites” and, therefore, sometimes claim they cannot be anti-Semitic or the word should apply to hatred directed toward them. Matt Lebovic gave the example of a 2015 speech by consumer rights advocate Ralph Nader: “[Supporters of Israel] know how to accuse people of anti-Semitism if any issue on Israel is criticized, even though the worst anti-Semitism in the world today is against Arabs and Arab-Americans.” He added, “The Semitic race is Arabs and Jews and Jews do not own the phrase anti-Semitism.”

This, however, is a semantic distortion that ignores the reality of Arab discrimination and hostility toward Jews. Arabs and other speakers of Semitic languages, like any other people, can indeed be anti-Semitic.

The ADL also argues that Marr’s use of the word “Antisemitismus” added “racial and pseudo-scientific overtones to the animus behind the word.” Furthermore, “hatred toward Jews, both today and in the past, goes beyond any false perception of a Jewish race; it is wrapped up in complicated historical, political, religious, and social dynamics.”

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) expressed a similar concern “that the hyphenated spelling allows for the possibility of something called ‘Semitism,’ which not only legitimizes a form of pseudo-scientific racial classification that was thoroughly discredited by association with Nazi ideology, but also divides the term, stripping it from its meaning of opposition and hatred toward Jews.” The IHRA also noted that “in German, French, Spanish and many other languages, the term was never hyphenated.”

Allison Kaplan Sommer noted this debate is not new. Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1994: “Anti-Semitism is altogether an absurd construction, since there is no such thing as ‘Semitism’ to which it might be opposed.”

Today, the hyphen is eschewed by scholars in the field and journals, such as the Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism and Antisemitism Studies. Several organizations that deal with the issue, such as the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, World Jewish Congress, Yad Vashem and the ADL have also dropped the hyphen. The Simon Wiesenthal Center has not.

Ken Jacobson, the ADL’s deputy national director, seemingly contradicted his organization’s position, telling the Times of Israel that the debate is “intellectually dueling and largely divorced from reality.” He said it “is an overreaction to Arab claims that they can’t be anti-Semites because they are a Semitic people.” Jacobson added that eliminating the hyphen “will not enhance anyone’s understanding and could even undermine a word that aptly conveys the power of this evil.”

Alvin H. Rosenfeld, director of Indiana University’s Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism, took a slightly different view. “Will spelling the word in an unhyphenated way as ‘antisemite’ and not ‘anti-Semite’ correct its misuse?” he asked. “Probably not for those who willfully misuse it, but for others, it may clarify that no one ever beat or cursed a Jew because he hated ‘Semitism,’ but only because he hated Jews.”

In April 2021, the Associated Press, generally considered the authority on usage for the media, announced it was changing its policy to eliminate the hyphen. The notification came via tweet without explanation. Meanwhiles, major newspapers such as the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Time Magazine have used the traditional spelling. It remains to be seen if AP’s decision will affect their policy.

Andrew Silow-Carroll, editor-in-chief of The New York Jewish Week told Kaplan, “Although the case for ‘antisemitism’ is strong, we are sticking with anti-Semitism because it appears to be the preferred spelling among most of the Jewish institutions we cover, and because it is consistent with our own newspaper’s practices going back decades.”

Other Jewish publications, including the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the Times of Israel, the Forward, the Jewish News Syndicate and Tablet all also retain the hyphen. The Jerusalem Post and the Algemeiner do not.

Most dictionaries, such as Merriam-Webster, and encyclopedias, such as Britannica also hyphenate the word. The word is also hyphenated in the U.S. State Department definition, but is not by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).

The IHRA argues by eliminating the hyphen “the meaning of the generic term for modern Jew-hatred is clear” with “no room for confusion or obfuscation”; however, there is little evidence of such misunderstanding. As Silow-Carroll said in editorial on the subject, “For some, the lowercase somehow demotes the word or concept itself, or represents a solution to a very minor and rarified problem.”

Other than the occasional claim by Arabs that they cannot be anti-Semitic, there is little evidence of confusion regarding the word’s usage and meaning. The Times of Israel reported that “very few experts expressed concern about anti-Semitism continuing to be spelled with a hyphen among the general public.” As noted above, dictionaries and the media use “anti-Semitism” and that is also the spelling we have adopted in the Jewish Virtual Library.

Sources: Vamberto Morais, A Short History of Anti-Semitism, (NY: W.W Norton and Co., 1976), p. 11.

Bernard Lewis, Semites & Anti-Semites, (NY: WW Norton &Co., 1986), p. 81.

Oxford English Dictionary; Webster’s Third International Dictionary.

“Spelling of antisemitism vs. anti-Semitism,” ADL.

Zack Rothbart, “Why ‘Anti-Semitism’ Was Not in the Original Oxford English Dictionary,” the Librarians, (April 5, 2020).

Allison Kaplan Sommer, “Anti-antisemitism? A Battle Rages Over the Jewish Hyphen,” Haaretz, (May 20, 2020).

Matt Lebovic, “What’s in a hyphen? Why writing anti-Semitism with a dash distorts its meaning,” Times of Israel, (August 23, 2018).

@APStylebook, April 23, 2021).

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/anti-semitism-or-antisemitism

Comedy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_irf-pj2IKk

Verifiable history on this subject begins with Hammurabi, not Cyrus or Ashoka. I doubt very much is either one influenced the other, nor that the history of other far away Emperors were even known to one another.

Their reigns and Laws were purely born of the fact that they had a sense of Social Responsibility for their own people, probably from some deprivation they had observed which they felt needed rectifying.

And one cannot omit that in reality they were political moves, and caused serious popularity of these rulers to grow.

Of course Buddha never saw himself as a ruler, but 100% the opposite.

@Michael Thanks. Gosh, I’m the last person to argue about ancient Western mythology, I know more about Asia. This is all I know 😀

And

Hi, Sebastien

There is a bibliography of scholoarly studies of various ancient chronologies, in downloadable ,pdf format, at

https://www.israpundit.org/semitism-vs-antisemitism-part-2-semitism-ascendant-the-story-of-ancient-mesopotamia/#respond

Like many others, I have reason to believe that Nimrod of the Bible (“Subduer of the Leopard”, according to Alexander Hyslop). descrobed in the Bible as the “Mighty Hunter” who went on to create the world’s first empire, was identical to Sargon the Great. The latter was fully described on an ancient mural excavated recently in the ruins of Nineveh.

The World History Encyclopedia lists

Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334 – 2279 BCE), and one Torah site compares him to Naram-sin and Nimrod, saying,

“The biblical Nimrod, however, is neither a wicked king, nor even a character unique to Israelite historiography. Instead, he is the composite Hebrew equivalent of the Sargonic dynasty’s two most famous Kings of Kish: Sargon, the first Semitic emperor, and his grandson Naram-Sin. The later editors of the Book of Genesis dropped much of the story and mistakenly identified the Mesopotamian Kish with the Hamitic Cush. The Nimrod tradition was thus lost, save for five verses in Genesis 10.”

https://www.thetorah.com/article/nimrod-mighty-hunter-and-king-who-was-he

I’m not Jewish, so I won’t be drawn into an argument about these things. As far as I’m concerned, Nimrod = either Sargon or Naram Sin, the man accepted by most as the founder of the Imperial Tradition that continues today (in Washington, DC)

@Michael Cyrus was 27 years older than Buddha. I just suggested that his example as a ruler might have inspired him to leave his kingdom and become a teacher. But, my first point was that the article completely leaves out that part of the world in its claim that there is a direct line between the Akkadian empire and the Judeo-Christian tradition and that there is no other source of compassionate and egalitarian rule in history.

Sebastien,

The three epicenters of religion in the world are Judaism-Christianity in Israel, Hinduism-Buddhism in northern India and Confucianism-Daoism in N. China. Around the time of the Jewish captivity in Babylon, Taoism and Confucianism were born in China, the Buddha was “enlightened” in Nepal, and the Platonic school began to fluorish in Greece. If the dates are meticulously handled, Zoroastrianism began during the same period.

Asoka was the first emperor to unite North and South India. He was a devotee of Buddhism, and the beginner of its spread. His empire was replaced by the Hindu Mauryan revival; and while southern India was lost to Buddhism, it spread from there to Southeast Asiia. Afghanistan and parts north were conquered by Alexander, and one of his generals (Menander) had a considerable kingdom in Afghanistan. Menander became a Buddhist; and through him the religion spread to China.

Cyrus was contemporary with the Jewish exiles in persia. If you want to find a source of inspiration for all these religions, don’t look to him. The entire Jewish nation had been exiled, and spread all over the civilized world. That probably made much more of an impact than the Persian Emperor.

Here’s a wild thought. Could Buddha have been influenced by Cyrus? He didn’t invent the principles of non-violence in Indian mysticism but he was a crown prince who gave up his kingdom and fortune – as well as his wife and child – to become a wandering monk and who then influenced kings and ordinary people of all classes and both sexes to be more humane and tolerant towards one another, as well as to animals, even in his own lifetime. I mean, who does that?

Where does Emperor Ashoka fit in all of this?

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2024/01/09/a-shining-star-of-kingship-emperor-ashoka-in-the-3rd-century-bce/

“a pillar in Afghanistan is inscribed in both Aramaic and Greek—demonstrating Ashoka’s desire to reach the many cultures of his kingdom.

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/south-asia/x97ec695a:1000-b-c-e-500ce-indo-gangetic-plain/a/the-pillars-of-ashoka

“Ambassadors of peace were sent to the Greek kingdoms in West Asia and Greece.”

https://vajiramandravi.com/quest-upsc-notes/ashoka/

Buddha 563 to 483 B.C. (though he was 40 when he began preaching.)

Cyrus 590-529 BC

Coincidence?