The Kremlin’s arrangement with the Syrian Kurds only adds more complexity for U.S. troops trying keep the focus on ISIS.

BY Joseph Trevithick. WAR ZONE. AUGUST 29, 2017

U.S. forces in northern Syria have exchanged fire with Turkish-backed rebels for the first time ever as the situation in the country continues to become ever more complex. To the west, Russian troops have moved into another area along the Syrian-Turkish border, cutting a deal with Kurdish fighters and effectively blocking both Turkish and American forces from entering the area, while exposing possible rifts between the United States and the groups it supports in the region.

The firefight involving American troops occurred near the contested city of Manbij in Syria, which has been a focal point for simmering tensions between United States and Turkish-supported factions since March 2017. This was the first time U.S. personnel had been directly involved in a clash, though, and thankfully no one was injured on either side.

“Our forces did receive fire and return fire and then moved to a secure location,” U.S. Army Colonel Ryan Dillion, the top spokesman for the U.S.-led task force fighting ISIS in Iraq and Syria, told the The Telegraph. “We have told Turkey it is not acceptable.”

U.S. officials have not named the specific group they faced off against, though they have made it clear they understand it was one from a loose coalition of ethnic Arab and Turkmen organizations that Turkish authorities are working with in Syria sometimes referred to as the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army(TFSA).

SDF snipers in Raqqa.

Between August 2016 and March 2017, Turkey had conducted its own unilateral operation against various Kurdish groups northern Syria, called Operation Euphrates Shield. After that ended, the country continued to support the TFSA as a hedge against the Kurds making further gains.

The Turkish government sees the Kurdish factions in Syria as an extension of a domestic terrorist group, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, better known by its Kurdish acronym PKK. Though the United States has also formally designated the PKK as terrorists, it insists the Kurds it is working with in Syria against ISIS, known as the People’s Protection Units or YPG, are separate and distinct.

The video below succinctly outlines Turkey’s position on the connections between the PKK and the YPG, which the United States disputes.

We at The War Zone have written at length in the past about how these complicated and often shifting allegiances, combined with the lack of clarity over America’s role in Syria after the defeat of ISIS – whatever that looks like – have increased the chances of U.S. troops and their partners ending up in a risky situation. With American special operators acting as de facto peacekeepers for months, this firefight near Manbij has seemed almost inevitable.

“Coalition troops will continue performing patrols within the Manbij Military Council area of control,” Eric Pahon, a Pentagon spokesman, told CNN after the incident with the Turkish-support rebels. “Coalition forces are there to monitor, deter hostilities and ensure all parties remain focused on our common enemy and the greatest threat to regional and world security, ISIS.”

Keeping the focus on ISIS is important for the United States, which has special operations forces closely assisting the American-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as they work to secure the city of Raqqa, which has been the terrorist group’s de facto capital. The SDF predominantly consists of element of the YPG, along with a smaller number of Arab fighters.

SDF fighters take cover in a building in Raqqa.

The fighting in Raqqa has been hard going and any diversion of effort or dangerous infighting might slow the offensive down even further. In July 2017, the Trump Administration ended support for certain Arab members of the so-called Vetted Syrian Opposition (VSO), a separate U.S. supported coalition, who had refused to stop battling the brutal regime of Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad and refocus on ISIS.

Earlier in August 2017, Jaish al Thuwar, a Kurdish faction aligned with the YPG and the SDF, reportedly fired a U.S.-supplied TOW anti-tank missile at Turkish-backed rebels as part of ongoing skirmishes. In that instance, the U.S. military said that while the Kurdish group was known to have connections with the SDF, it was not an American-supported group itself. The United States also trying to distance itself from these breakaway Kurdish elements.

In line with keeping things laser focused on crushing ISIS, earlier in August 2017, the United States said it would establish a shared ceasefire monitoring center with Russian and Jordanian personnel in Jordan’s capital Amman. The U.S. government had previously brokered a deal with the Kremlin, along with Jordan and Israel, to establish a safe zone of sorts in southern Syria.

Turkish troops head toward the Syrian border in an armored vehicle in 2016.

But as the threat of ISIS begins to recede, it seems clear that many factions in Syria are already looking to the future, if they haven’t been before now. At the same time, there appear to be serious rifts starting to form between the United States and its Syrian partners, many of whom have their own agendas.

One of the first indications of this was on Aug. 23, 2017, when an SDF spokesman suggested the U.S. military was planning to have a long-term presence in Syria after ISIS was gone. The Pentagon and the State Department quickly refuted this claim.

Then, on Aug. 25, 2017, the SDF’s Deir al-Zor Council, further to the west of Raqqa, said it would soon begin a separate offensive against ISIS in that province, according to its commander Ahmed Abu Khawla. This Arab component of the U.S.-supported rebel coalition said it had just bolstered its ranks with approximately 800 new fighters from the Syrian Elite Army, yet another separate, but SDF-aligned faction.

When asked about this, though, Colonel Dillon told Reuters that the focus remained on Raqqa alone. It was unclear what, if any support the U.S. military would be willing to provide for a push into Deir al-Zor, where Russian troops and Iranian-backed militias are also seeking control. Iran in particular is interested in creating a physical lifeline between itself and its allies in Syria and Lebanon, via Iraq.

Now it also seems that the YPG may be growing concerned about the U.S. government’s intentions in the country and its willingness or ability to guarantee the group’s security. On Aug. 29, 2017, Russian troops moved into the town of Afrin, a major hub for the Kurdish group, mimicking in many ways the appearance of U.S. Army Rangers in Strykers in and around Manbij four moths earlier. Most notably, the Russian vehicles, like their American counterparts, also sported large national flags making sure there was no confusion about the vehicles’ operators.

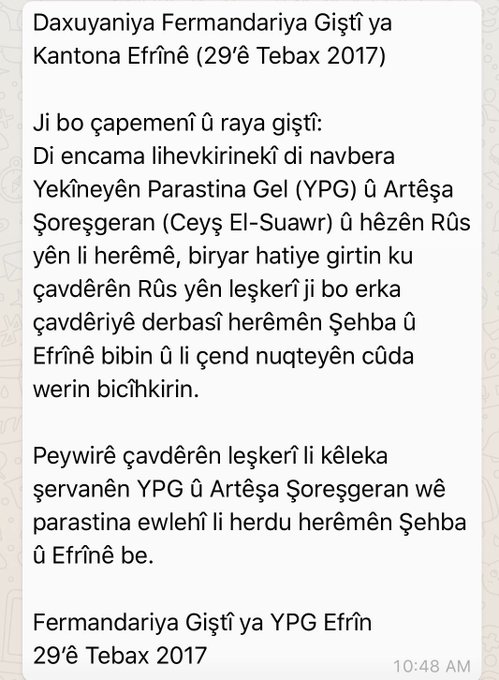

Russia and the YPG’s leadership struck a deal that appeared to effectively keep Turkey and its allies, as well as the United States and its coalition, out of the area. “The duty of the military observers is to maintain security conditions,” the Kurdish group said, according to Iraqi Kurdish news outlet Rudaw.

The arrangement comes less than a month after the YPG warned that harassment from Turkish supported groups could threaten the Raqqa offensive, adding that it had informed its American partners about the issue. “If the Turkish state continued its occupation attacks against Afrin and Shahba, the Raqqa operation will not continue,” the YPG’s General Ccmmander Sipan Hemo declared.

YPG confirms Russian military observers are in Afrin & Shahba region after a deal between YPG, Jaysh Thuwar and Russia

However, if this weren’t complicated enough, there were reports in July 2017 that this might be part of a larger agreement between the Kremlin and Turkish officials, which would see Russian and Syrian troops cede the city of Idlib to Turkey’s Arab and Turkmen partners.

Russia, Turkey and Iran have all been separately negotiating for a series of so-called “de-escalation zones” throughout Syria. On Aug. 24, 2017, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that a new safe zone would soon appear around Idlib, but made no mention of any plans for Afrin.

Militiamen with the Pro-Syrian government Desert Falcons in Palmyra in 2016.

Syria, Russia, and Iran are separately looking to be coordinating their efforts in order to shore up their relative positions and protect their increasingly intertwined interests in the region. Most worrisome, Iran appears to be actively supporting the Syrian government’s work on new arms factories, which may be able to produce ballistic missiles.

There is evidence that Russia, or Syria with Russian-supplied weaponry, may have positioned long-range surface-to-air missiles at this site to provide an active defense. On Aug. 25, 2017, the Russian military announced it had formally linked its air defense assets in the country with Assad’s own air defense network.

Again, same guy is sharing photo/info about possible new site of S300/400 in Syria. pic.twitter.com/u3jrRzbYiL

@obretix manage to find this place,height of 1300m, clear view over wast area of Syrian desert/east. One in Latakia is’blinded’by mountains pic.twitter.com/lBroqXvkxd

Needless to say, the United States was already in the middle of a complex multi-side conflict in Syria. The situation is only getting more complicated by the day and the temerity of the various factions seems to be growing at an equal pace as they attempt to begin staking their claims for whatever happens when ISIS finally breaks.

“You’ve got to really play this thing very carefully. … The closer we get [to defeating ISIS] the more complex it gets,” Secretary of Defense James Mattis said back in June 2017. “We just refuse to get drawn into a fight there in the Syria civil war.”

These first remarks are as true as ever and don’t look to be changing any time soon. However, the United States is increasingly in danger of getting pulled into the country’s long-running civil conflict, whether it says it doesn’t want to be involved or not.

The act of not getting involved carries its own weight, too, which runs the risk of alienating important partners before the coalition declares victory against ISIS.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.