Peloni: Prof. Gil-White provides a much needed review of the development and deployment of the psychological warfare in the US. The public-private manipulation of the American people has long been a feature of American society.

How psychological warfare became the science of ´communication´ and swallowed our meaning-making institutions

Francisco Gil-White | July 12, 2024

- In the 1930s, a large scientific project studied how the mass media could influence democratic citizenries.

- These scientists were then recruited to the US government’s psychological warfare programs in WWII.

- After the war, the same scientists became university professors of ‘communications,’ clandestinely funded by US Intelligence.

- These university departments of ‘communications’ train essentially everyone who works in the media.

In war, if your morale is high and the enemy has lost the will to fight, then—other things equal—you’ve won the war. Or if your enemy is utterly confused but you know what you are doing, then—other things equal—you’ve won the war.

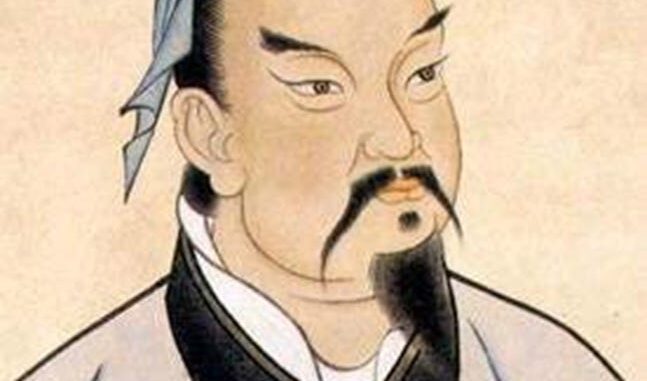

How to achieve such asymmetries? By managing the enemy’s reality. This is called ‘psychological warfare.’ The principle—as old as war itself—has been explicitly theorized about for a very long time. For example, in The Art of War, written ca. 400 before Jesus (perhaps earlier), an immortally famous treatise by Chinese strategist ‘Sun Tzu’ (or by a collection of ancient military geniuses glossed with his name).

Sun Tzu repeatedly emphasizes that, if you can effectively manage the enemy’s reality, then you might not even need to fight. The best strategist defeats the enemy with deceit before the battle has even begun because…

Supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.

—Sun Tzu

But who is the enemy?

As many before me have recognized, Sun Tzu’s insights have myriad applications beyond literal warfare to many other situations of conflict, broadly construed. His principles and recommendations, abstracted from the context of warfare, are useful to the big bosses who compete for world power when they make geopolitical moves in times of ‘peace.’ And they are equally useful, to the same bosses, when they move against domestic ‘enemies.’

A dark realization: whatever the bosses learn in war about managing the enemy’s reality will help them manage the citizen’s reality, with profits accruing to their own ‘boss power.’

This very insight, more cheerily expressed, popped into the head of one Edward Bernays, a psychological warfare expert in the employ of the CPI (Committee on Public Information), the US government’s propaganda outfit during WWI.

“ ‘There was one basic lesson I learned in the CPI, that efforts comparable to those applied by the CPI to affect the attitudes of the enemy, of neutrals, and people of this country could be applied with equal facility to peacetime pursuits. In other words, what could be done for a nation at war could be done for organizations and people in a nation at peace.’ ”1

That’s a quote you may want to take seriously. Because Edward Bernays was not musing idly about possible applications of his trade against US civilians—he put his money where his mouth was. This creative legend, High Jedi of reality management, father of marketing and public relations, no less, boasted that he could change a nation’s culture. And he did. Tobacco companies, to cite just one example, paid him a fortune to get women smoking (there was a taboo against that). And he got it done.

Though I have no record of any such conversation, I can well imagine the advice that Bernays might have given to his former government bosses.

“Look,” I picture him saying, “you can sometimes stay in power by firing on civilians, and we all know there’s been quite a lot of that going on for decades in our blessed United States—ahem!—starting with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 (what we sometimes call, and not for nothing, the Great Upheaval). But firing on starving workers is messy business. And risky. You’ve seen it backfire (just think back to the Ludlow Massacre scandal right before the world war, and all the trouble that brought to the poor Rockefellers). A lot more of that and we’ll have a revolution. We needn’t run such risks! Why not listen to Sun Tzu? Why not own the mass media and the established, high-prestige universities so that you can twist and manipulate facts and meanings? Why not manage the reality that people are reacting to? If you can do that, you can make them do anything, and they’ll do it willingly. You break the enemy’s resistance, as Sun Tzu advises, without fighting!”

As I said, I have no record of any such exchange. But what Bernays did himself put on the record was his utter confidence that his former bosses had acted as though he’d given them precisely that advice. By the late 1920s, according to Bernays, a simulated democracy had already been established.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.”2

According to Bernays this was very good for us. “The orderly function of group life,” he said, was simply impossible unless we had “our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” These men were a “trifling fraction,” the select few “who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses …, who pull the wires which control the public mind, … [and] harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”3

This extreme diagnosis of US “democratic society,” as Bernays insisted in calling it, appeared in the opening lines of his candidly titled book Propaganda (in my view a deeply and playfully cynical work). It was published in the year 1928.

Can we possibly accept Bernays’ claims? Can we accept that US bosses were already thoroughly managing the citizen’s reality in the year 1928?

What you can accept is a function of what you already know. Depending on what you know, certain things will seem more or less plausible.

If you are like most US citizens, then you know very little about World War I, notwithstanding its recency and tremendous importance. (No shame accrues to you: the education system failed you). And you’ll likely know less-than-nothing about the great reach of US President Woodrow Wilson’s wartime CPI. In which case it will seem like Bernays must be exaggerating. You will not accept his claims.

You may take a different view, however, if you are familiar with the work of historians of the Wilson administration, and in particular those interested in the CPI. My favorite entry here is Jonathan Auerbach’s Weapons of Democracy: Propaganda, Progressivism, and American Public Opinion. If you’ve read Auerbach, you’ll know that Woodrow Wilson—and his aide-de camp cum eminence grise ‘Colonel’ Edward M. House—achieved near-totalitarian control over information during World War I. (More on that soon!)

Knowing all that, you’ll have to wonder: Would US bosses ever give up such power? I mean, do we have examples of someone seizing power and then giving it up without being forced to? (Okay, other than Cincinnatus?) According to Orwell, that’s not how the ambition for power works.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.