Francisco Gil-White | The Management of Reality Substack | May 3, 2024

Developments in Doha’s West Bay district have seen an increase in the population density of the area with the construction of several high-rises. Source: Wikipedia.

Developments in Doha’s West Bay district have seen an increase in the population density of the area with the construction of several high-rises. Source: Wikipedia.

“Qatar is a transit and destination country for men and women trafficked for the purposes of involuntary servitude.”—US State Department Trafficking in Persons Report 2009.

If you inferred from my headline that I would report on the progress of anti-Qatar protests on US campuses, that’s on you. I didn’t say that. And there are no such protests.

My headline doesn’t lie. It just says: “Paradox: the anti-Qatar protests on US campuses.” As a sentence, it is incomplete, and one may certainly close it like so: “Paradox: the anti-Qatar protests on US campuses are nonexistent.” That’s a grammatical sentence. And that’s the state of affairs that I can report: there are no anti-Qatar protests on US campuses.

One could argue that there should be such protests.

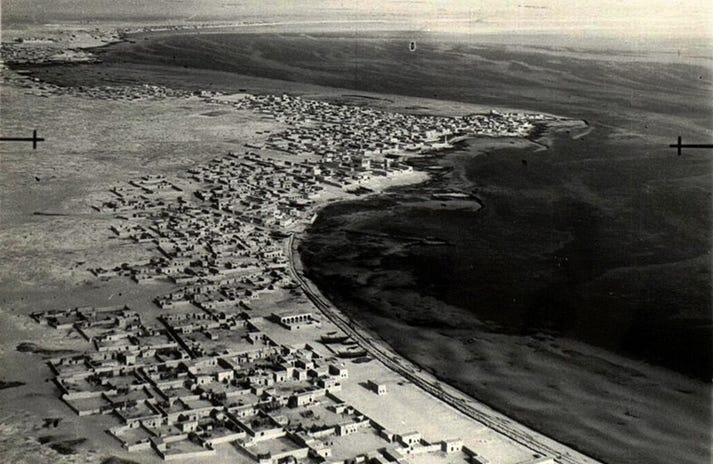

Why? Well, Qatar is fabulously rich today, thanks to some of the largest gas reserves in the entire world, and from that, and from the very modern buildings going up in Doha, Qatar’s capital, you might get the impression that Qatar must be a modern country. It is not. Qatar is a primitive country whose labor force is made up of a giant population of slaves.

But nobody on US campuses is denouncing that. Why not? It’s a question worth asking, I believe. But let me phrase it thus:

- Why is there so much agitation ostensibly in favor of the Arab Palestinians, but not one word to defend the slaves that languish oppressed in Qatar?

These are slave slaves, not metaphorical slaves. They are owned. They have a master. They can’t leave. They are mercilessly exploited. Many are raped. Millions of people.

Lest you think I am exaggerating, consider that, in 2005, Gulf News reported this:

“International human rights groups had raised the alarm over the exploitation of children from Asian and African countries by traffickers who pay impoverished parents paltry sums or kidnap their victims to smuggle them into the Gulf.”1

“The Gulf” is a reference to the Persian Gulf, where several sharia-law States, among them Qatar, keep a giant multitude of slaves (yes, in the 21st century).

The title of the article quoted above was: ‘Qatar to combat human trafficking with six-point plan,’ which may leave the reader with a good feeling: the Emirate of Qatar, a human trafficking world capital, is taking the matter in hand and will combat this scourge. So how did that go? Well, in 2009, a full four years later, the US Department of State, the foreign ministry of Qatar’s closest and most precious ally, the United States, said this:

“Qatar is [still] a transit and destination country for men and women trafficked for the purposes of involuntary servitude and, to a lesser extent, commercial sexual exploitation. Men and women from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Ethiopia, Sudan, Thailand, Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and China voluntarily travel to Qatar as laborers and domestic servants, but some subsequently face conditions indicative of involuntary servitude. These conditions include threats of serious harm, including financial harm; job switching; withholding of pay; charging workers for benefits for which the employer is responsible; restrictions on freedom of movement, including the confiscation of passports and travel documents and the withholding of exit permits; arbitrary detention; threats of legal action and deportation; false charges; and physical, mental and sexual abuse.”2

I must point out that the US State Department would prefer not to have to write that, as Qatari bosses are the most intimate allies of US bosses, and that relationship is managed by the US Department of State. So it is safe to assume that reality is far worse than any State Department report.

And this reality is no trifle: this is slavery we are talking about.

So I ask again: Why no anti-Qatar protests on US campuses?

Of course, if the issue were compassion for those suffering—which is a very general category—I could have asked (as a friend of mine just pointed out): Why isn’t anybody protesting the near-total absence of food deliveries for people starving to death in Sudan? Campus protesters in the US seem to care nothing about them. We are talking about some 18 million people at risk of starving to death.

But I am asking about Qatar—specifically—because the explicitly ‘leftist’ protesters on US campuses claim to be very interested in freedom. “Free, Free Palestine,” they chant. Okay. Let’s say you care about freedom. But if freedom—rather than starvation—is your pet issue, then why are the Arab Palestinians, specifically, deserving of so much emotion on this question?

A lot of emotion has been poured. ‘Pro-Palestinian’ campus protesters in the US (and elsewhere) are most agitated, taking entire universities hostage—even destroying property—and making it impossible for others to study. They are turning entire cities upside down. All of it on account, they say, of the Arab Palestinians. And the question, they say, is freedom.

So what about all those slaves in Qatar? And the slaves elsewhere in the Arab Muslim world? We are talking about several million slaves. They are not free.

I understand that a Western ‘leftist’ protester needs to make some strategic economic decisions. The day has 24 hours and eight of those (or so) need to be spent sleeping in your tent in your makeshift encampment on the university campus. There just isn’t enough time in the day to protest every act of oppression. I get that. But if you are going to demand freedom for just one category of people, how about all those slaves in Qatar?

They seem more sympathetic to me. They didn’t elect a terrorist organization, Hamas, to govern them. They didn’t collaborate in the creation of a terrorist State dedicated to commit genocide against another people, which then sent terrorists to kill on sight or torture to death 1,200 innocent civilians on October 7th and also took some 250 hostages to torture and rape. And, by golly, those poor folk in Qatar are slaves. Slaves!

Can’t a Western ‘leftist’ take some interest in the slaves?

What we have here is a political paradox. Consider:

- The ‘pro-Palestinian’ agitators take sides against Israel. Since Hamas is fighting Israel, this means they support Hamas. Much of the agitation has been quite explicit on that score. Many protesters have even adopted the phrase, “A free Palestine from the [Jordan] river to the [Mediterranean] sea,” which is Hamas jihadi code for the extermination of the Israeli Jews.

- Consistent with that, we have seen campus protesters take a position even against US citizens who are Jewish. That’s racist, of course. But my angle here is the question of slavery. What is noteworthy, from that perspective, is this: the Jews trace their origins to a slave revolt (Book of Exodus), and it was their moral principles, inherited to Christians, that made possible the abolition of slavery in the West. Were it not for the influence of Jewish ethics, these campus protesters would still be slaves.

- By stark contrast, Hamas has a pro-slavery ideology, because Hamas is a jihadi organization, and jihadis believe in enslaving any infidels they don’t kill.3 Indeed, Hamas is financed most of all by—drum roll…—the Emirate of Qatar. And Qatar is a jihadi—therefore pro-slavery—State, which (did I mention this?) is already chock-full of slaves.

So here’s the paradox: nothing is more rigorously or traditionally ‘leftist’ than the fight to abolish slavery, and yet these campus protesters, who present as ‘leftists,’ are agitating for the slave-masters against those who taught us to abolish slavery.

What explains that? How did Western leftists come to adopt a pro-slavery position?

This here is a diagnostic issue—I promise you. In other words, the explanation of this paradox reveals the structure of the entire system. Below I will do the following:

- Give a historical overview of slavery in Qatar.

- Give a proximate answer to the question: Why no leftist anti-Qatar protests?

- Give an ultimate answer to the question: Why no leftist anti-Qatar protests?

This process will reveal the structure of the system.

Two annotations

Before I document slavery in Qatar and other sharia-law States, I must make two annotations.

The first is that I will not be speaking here of the millions of wives and daughters of Muslim men, fully half of the population and every one of them a bona-fide slave in sharia-law States such as Qatar.

This misogynistic barbarity, this misogynistic outrage, merely criticized in the West, is a crime against humanity that should scandalize beet-red every allegedly ‘leftist’ ‘social-justice warrior.’ But this is not my present quarry. My quarry in this piece are the millions of men, women, and children from other countries who’ve been imported into sharia-law States such as Qatar and turned into slaves.

The second annotation is that Qataris are hardly alone in keeping slaves. This is happening all over the Arab Muslim world. I will keep a special focus on Qatar, and secondarily on Saudi Arabia (because they are both key US allies), but please keep in mind that this is happening all over Arab Muslim ‘civilization,’ and especially in explicit sharia-law States such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Okay, here we go…

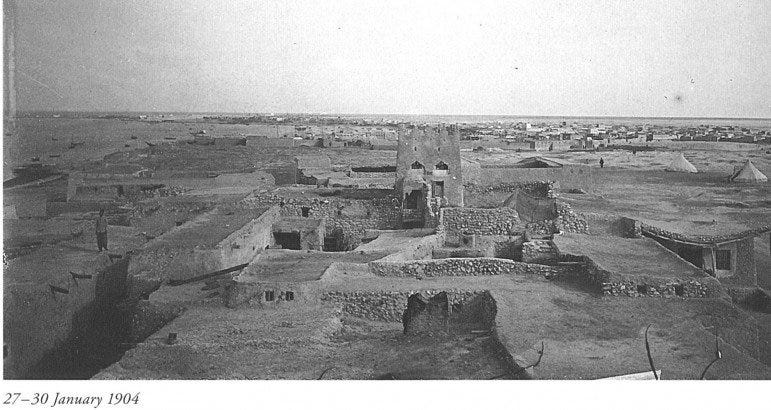

The early 20th century

In 1907, long before the present wave of pro-Islam political correctness in the West, which has represented Islam as ‘the religion of peace,’ the French scholar of Islam Clement Huart wrote that a conquering Muslim state, when considering persons in the conquered population, would apply the following jihadi rule:

“The status of slave is presumed until the contrary is proved … Conversion to Islam does not alter that status since it is legal to own a Muslim slave.”4

This never stopped. Indeed, according to the Wikipedia article ‘Slavery in Qatar,’

“The British Empire gained control of Qatar in the 1890s and signed the 1926 Slavery Convention to fight enslavement in all land under their control. However, they doubted their ability to stop Qataris from continuing slavery, so the British policy was therefore to assure the League of Nations that Qatar followed the same anti-slavery treaties signed by the British and prevent observation of the area that could disprove the claims. In the 1940s, there were several suggestions made by the British to combat the slave trade and the slavery in the region, but none was considered enforceable on the Qataris.

The fact that the British Empire felt it was too much of a bother to try and get Qataris to free their slaves—even though Qatar is almost the smallest country in the world and impossible to defend, militarily—speaks volumes. If the most powerful country in the world, the British Empire, wholly responsible for defending Qatari borders, found Qataris so rabidly attached to oppressing their slaves that it decided not to bother, what chance is there that Qataris will reform by themselves?

Zero chance, as we shall see.

The mid-20th century

Qatar officially practiced chattel slavery—in a form that treats humans who are the legal property of another as basically an animal or a thing—until the year 1952, when this was made officially illegal.

But that was a pretense; slavery was not really abolished. It was just given a new name, as Wikipedia explains: the so-called Kafala system, adopted in “Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.”

“The [kafala] system requires all migrant workers to have an in-country sponsor, usually their employer, who is responsible for their visa and legal status. This practice has been criticized by human rights organizations for creating easy opportunities for the exploitation of workers, as many employers take away passports and abuse their workers with little chance of legal repercussions. The International Trade Union Confederation estimated 2.4 million enslaved domestic workers in the Gulf countries in its 2014 report, mainly from India, Sri Lanka, Philippines and Nepal.” (my emphasis)

“Enslaved” is correct. There is no exaggeration in the above text. This is not a metaphor. When you can abuse your workers “with little chance of legal repercussions” and you “take away passports,” so that these workers—abused with impunity—also cannot leave, what you have are slaves. It fits the technical, traditional definition of chattel slavery.

In 1964, in a short article that appeared in International Migration Digest titled ‘Forced Migration: The Slave Trade Still Flourishes,’ the author wrote that,

“Slavery countenanced by law or custom may be found today in Africa, Asia, and Asia Minor. Specific sites include Aden, Kuwait, Muscat, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia …, parts of the Sudan, and Yemen.”

Two years earlier, Saudi Arabia had “announced its ‘termination’ [of slavery], but whether that means that their 500,000 old slaves are freed or no new ones may be purchased,” these authors wrote, “is not clear.”5 But it was clear. There was no termination of slavery. The Saudis just went ahead and called it the kafala system. But that’s slavery.

The late 20th century

Okay, but how about more recently? Well, In 1982, Myron Weiner wrote in Population and Development Review that

“In the five small oil-producing states that line the Persian Gulf—Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman—two thirds of the labor force is imported.”6

Whoa! Two thirds: 66%. Were these imported workers slaves? Yes. Imported workers are imported via the kafala system.

And Saudi Arabia? In 1987, Aharon Layish, writing about Saudi Arabia in the Journal of the American Oriental Society, stated that:

“Slavery and concubinage, firmly anchored in the shari’a and in reality, were abolished in 1962, mainly in deference to world [meaning Western] opinion. … At the same time it appears that slavery, and especially concubinage, have not yet completely disappeared.”7 (bracket is mine)

I must confess to not having the slightest idea what Layish could possibly mean by his statement that slavery and concubinage in the Muslim world are “firmly anchored … in reality.” But notice that in 1987, a full twenty-five years after the supposed abolition of slavery in Saudi Arabia, scholars of this country conceded in print that slavery there had not ended.

This admission is quite significant because by 1987 Western scholarship of Islam and the Near East had become deferential rather than critical, and the new ‘scholars’ of Islam were already working hard to diminish the impression that there is anything wrong with this religion. Layish’s article was in fact a defense of the view that Saudi Arabia was becoming more moderate! And that’s why he wrote that “slavery, and especially concubinage, have not yet completely disappeared,” as if they had been disappearing and were almost completely gone (by such phrasings is reality managed…). Layish should have written that slavery and concubinage remained rampant and were perhaps increasing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.