T. Belman. I highly recommend the books of Joseph Roth. I read the Radetsky March and others about 30 years ago..

By Joseph Epstein |JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS

In Ostend, his book about the German and Austrian émigré literary group that gathered in the Belgian resort town after Hitler came to power, Volker Weidermann describes Joseph Roth, the most talented of these writers, looking “like a mournful seal that has wandered accidentally onto dry land.” Roth was small, thin yet pot-bellied, slightly hunched over, with a chosen nose, a bad liver, and missing lots of teeth. He began most mornings, like the serious alcoholic that he was, vomiting. Always in flight, one of the world’s permanent transients, Roth was a one-man diaspora: “Why do you people roam around so much in the world?” asks a Galician peasant in one of his novels. “The devil sends you from one place to another.”

Joseph Roth happens also to have been a marvelous writer, and he might have gone on to be a great one had he not died in 1939, in his 45th year. (He is of that uncharmed circle of writers—Chekhov, Orwell, F. Scott Fitzgerald—who died before they reached 50.) Not the least of Roth’s marvels was his astonishing productivity. In his short career between 1923 and 1939, he published, in German, no fewer than 15 novels, a batch of short stories, and, by his own reckoning in 1933, something on the order of 3,500 newspaper articles, most of them of the genre known as feuilleton, those short, literary, free-form, usually non-political essays that were once a staple in French and German newspapers. None of his writing that I have read, even the most ephemeral journalism, is without its felicitous touches, its arresting observations, its striking evidence of a first-class literary mind at work.

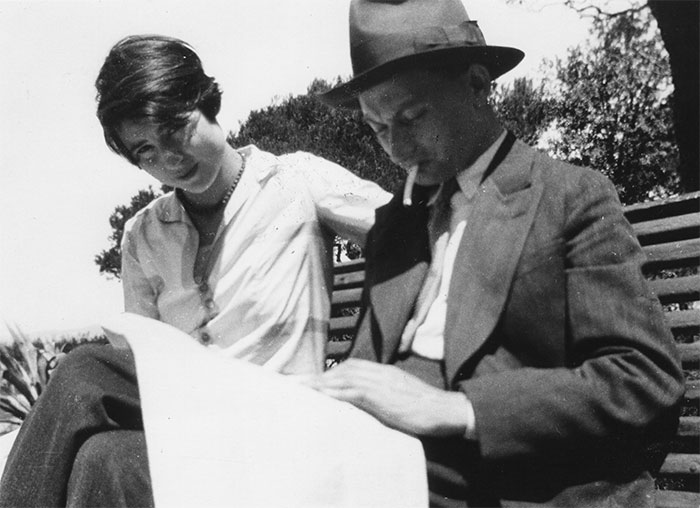

Joseph Roth and his wife, Friederike, in the south of France, 1925. (Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute.)

Roth’s work is bedizened with metaphor, laced with simile. In the short story “Strawberries” one finds: “The sun came out, as though back from holiday.” “Later they planted pansies on the lawn, beautiful big pansies with soft, clever faces.” Crows “were at hand like bad news, they were remote like gloomy premonitions.” In The Emperor’s Tomb (1938) there falls “a rough sleet, failed snow and wretched brother to hail.” In the same novel a landlady appears “as broad in the beam as a tugboat.” In The Radetzky March expensive “wine flowed from the bottle with a tender purr.”

A strong taste for aphorism and risky generalization runs through all Roth’s work. In his early novel Hotel Savoy (1924) one finds: “All educated words are shameful. In ordinary speech you couldn’t say anything so unpleasant.” “Industry is God’s severest punishment.” “Women make their mistakes not out of carelessness or frivolity, but because they are very unhappy.” In The Emperor’s Tomb we learn that “honor is an anesthetic, and what it anaestheticized in us was death and foreboding” and “to conceal and deny frailty can only be heroic.” Joseph Roth was a writer, as was once said of Henry James, “assailed by the perceptions.”

At the same time, Roth’s eye for detail is unerring. In a story called “The Place I Want to Tell You About,” a character, setting out for Vienna, remembers “the umbrella with the ivory handle” before leaving. That ivory handle puts one in the room. A minor character in The Radetzky March is “the father of three children and the husband of a disappointed wife.” Another minor character in the same novel reveals “a powerful set of teeth, broad and yellow, a stout protective grill that filtered his speech.” A woman in the story “The Triumph of Beauty” has “a long but unexciting chin”; a man in the same story has a large square torso that makes him look like “a wardrobe wearing a blazer.” Travelling in steerage to America the family at the center of his novel Job: The Story of a Simple Man sleeps along with 20 or so others, “and from the movements each made on the hard beds, the beams trembled and the little yellow electric bulbs swung softly.” In his preface to The Nigger of the Narcissus and “The Secret Sharer,” Joseph Conrad wrote: “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel, it is, before all, to make you see. That and no more—and it is everything.” Roth understood.

A second marvel is that Joseph Roth was able to get as much done as he did under the strained conditions in which he worked. The strain was financial. Roth was a money writer, less by temperament than by necessity. A spendthrift always hovering on personal pauperdom, he had the additional heavy expense of a wife who fairly early in his marriage had to be placed in various sanatoria for schizophrenia. (In 1940, Friederike Roth was removed from a Viennese hospital and murdered under the Nazis’ euthanasia program.) Much in Roth’s letters—published recently in English as Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters—is given over to pressing publishers and newspaper editors for the payment of advances or for raising his fees, complaints about his barely scraping by, and the expressions of guilt because of his need to borrow from friends, chief among them the commercially much more successful Stefan Zweig, who was his dearest friend and practically his patron.

Many of Joseph Roth’s novels are of modest length, some barely beyond that of the standard novella. (His final work, The Legend of the Holy Drinker, published in 1939, runs to 49 pages.) The four of these novels I find most accomplished are Right and Left (1929), Job: The Story of a Simple Man (1930), The Emperor’s Tomb (1938), and, the lengthiest and most fully realized, The Radetzky March (1932). An account of life under and a tribute to the Dual Monarchy, as the Austro-Habsburg dynasty was also known, The Radetzky March is one of those extraordinary works of fiction that, like Lampedusa’s The Leopard, cannot be anticipated by what has gone before in its author’s oeuvre. (Michael Hofmann, Roth’s ablest translator and most penetrating critic, writes of “the accelerated development otherwise known as genius.”) The novel’s title derives from Johann Strauss’s famous march and is one of those books that when two people meet who discover they have both read it sends a pleasing shock of recognition between them, followed by the bond of mutual admiration for an extraordinary work of literary art.

The range and variety of Roth’s fiction are impressive. That fellow in Eliot’s great poem might have done the police in different voices, but Roth in his fiction could do poor shtetl Jews and the Emperor Franz Joseph, Polish nobles and Ruthenian peasants, down-and-outs and successful entrepreneurs, Romanians, Czechs, Poles, Germans, Cossacks—in short, the entire Austro-Habsburg Empire, and all in perfect pitch.

Moses Joseph Roth was born in 1894 in Brody, a Galician town of roughly 18,000 people, two-thirds of whom were Jewish, on the border between Poland and Ukraine, 54 miles north-east of Lemberg (now called Lviv). He never knew his father, who died in a mental asylum. In 1913 he earned a scholarship to the University of Lemberg, and after a year there went on to the University of Vienna, where he dropped the Moses from his name and claimed his father was (variously) a Polish count, an Austrian railway official, an army officer, and a munitions manufacturer; at one point he took briefly to wearing a monocle; later he would claim to have been an officer, not the enlisted man that he was in the First World War. All this in the attempt to shed the identity of the Ostjude, then held in much contempt in Vienna. This outsider, outlander even, became the great chronicler, and eventually the prime mourner, for the Dual Monarchy, later in life declaring himself a monarchist. On his gravestone in a cemetery outside Paris the words “Écrivain Autrichien” are engraved.

Of the cards dealt at birth, not the least significant is that of the time into which one was born. Here Roth drew a poor card. He came into his majority with the onset of the Russian Revolution and the First World War—“world,” as a character in The Emperor’s Tomb says, “because of it, we lost a whole world”—and left it as Hitler was gearing up the machinery for his Final Solution. (Communism, he noted in a letter to Zweig, “spawned Fascism and Nazism and hatred for intellectual freedom.”) Meanwhile, the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Treaty of Versailles finished off the Dual Monarchy, reducing what was once a sprawling empire to a shriveled Austrian Republic. The multitudinous fatherland Roth knew as a young man evaporated in the fog of nationalism. In his splendid story “The Bust of the Emperor,” Roth quotes the Austrian playwright Grillparzer on the fate of the Dual Monarchy: “From humanity via nationality to bestiality.”

What Roth valued in the Austro-Habsburg Empire was the fluidity it allowed its subjects, who could travel from country to country without the aid of passports or papers, and its discouragement of nationalism, which worked against the nationless Jewish people. “I love Austria,” he wrote in 1933. “I view it as cowardice not to use this moment to say the Habsburgs must return.” In 1935 he wrote to assure Stefan Zweig that “the Habsburgs will return . . . Austria will be a monarchy.” Before the approaching Anschluss of 1938 he even attempted, through the offices of Kurt Schuschnigg, the chancellor of the Federal State of Austria, to restore the monarchy by installing Otto von Habsburg, heir of the Emperor Franz Joseph, on the empty throne.

Not that there wasn’t anti-Semitism, that endemic disease, under the Dual Monarchy. Nor was it absent in France, where, after Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, Roth lived out his last years, but, as he wrote in a strange little book called The Wandering Jews (1927), there “it is not one hundred proof. Eastern Jews, accustomed to a far stronger, cruder, more brutal anti-Semitism, are perfectly happy with the French version of it.” Never other than unpredictable, Roth, that most cosmopolitan of Jews, valued the shtetl Jews of Eastern Europe above all. He valued their Jewish authenticity and felt that those Jews who had taken up the assimilated life in Germany and elsewhere and pretended to a patriotism that ultimately wasn’t returned to them, “those rich Jews,” as he wrote in Right and Left, “the ones who want more than anything else to be native Berliners” and who “go on celebrating their holiest festivals in a kind of shamefaced secrecy, but Christmas publicly, and for all to see,” these were the Jews most deceived and hence most to be pitied.

The real subject at the heart of The Wandering Jews is the distinctiveness of Jews. “Of all the world’s poor, the poor Jew,” Roth writes, “is surely the most conservative . . . he refuses to be a proletarian.” The difference between the Russian and the Jewish peasant is that “the Russian is a peasant first and a Russian second; the Jew is Jew first and then peasant.” Roth underscores the intellectual cast of the Jews. “They are a people that has had no illiterates for nearly two thousand years now.” Not wishing to fight other people’s wars, “the Eastern Jews were the most heroic of pacifists. They were martyrs for pacifism. They chose crippledom”—a reference, this, to the Jews who inflicted self-mutilations to avoid fighting in the army of the tsar, especially since only in Russia was anti-Semitism, more than the usual free-floating version, “a pillar of government.”

Zionism was the best answer to the Jewish question for Roth, “for it is surely better to be a nation than to be mistreated by one.” The Jews “are forced to be a ‘nation’ by the nationalism of the others,” and “if one must be patriotic, then at least let it be for a country of one’s own.” Even though “the American cousin is the last hope of every Eastern Jewish family,” it is only the presence of blacks that “insure[s] the Jews won’t have the lowest status in America.” Whether Roth would have made aliyah had he lived longer cannot be known—toward the end of his life he called himself a Catholic—but there is little doubt that he yearned for an end to “the flight out of Egypt, which has been in progress now for thousands of years.

Intensely Jewish though he was, apart from Job: The Story of a Simple Man, his novel with a shtetl setting, Jews tend to figure only peripherally in Roth’s fiction. Until the small commercial success of Job, Roth was in fact better known for his journalism. His early fiction is always brilliant but emotionally spare. Roth wrote against the grain of the ascending modernism of his day. He thought little of James Joyce. “No Gide! No Proust! Nor anything of the sort,” he wrote to a journalist and novelist named Hans Natonek. He criticized Natonek’s penchant for abstraction. “A novel is not the place for abstractions. Leave that to Thomas Mann.” In his novel Right and Left, the criterion he sets for a wealthy character’s buying art is “that a picture should repel his senses and intelligence. Only then could he be sure of having bought a valuable modern work.”

In Right and Left, Roth lays out the fictional program under which he worked, holding foremost that “passions and beliefs are tangled in the hearts and minds of men, and there is no such thing as psychological consistency.” Change interested him more than consistency. We are, he held, chameleons all, changing character with the opportunities life provides us: “The more opportunities life gave us, the more beings it revealed in us. A man might die because he hadn’t experienced anything, and had been just one person all his life.” Roth the novelist believed that in the drive through life none of us is really at the wheel.

“No interest in day-to-day politics,” Roth wrote to Natonek. “They distort. They distort the human.” Elsewhere he referred to “the hollow pathos of revolutionaries.” In a brilliant passage in “The Bust of the Emperor,” he writes that “the inclinations and disinclinations of the people are grounded in reality.” Reality is quotidian life. “After they have read the newspapers, listened to the speeches, elected the representatives, and discussed the news with their friends, the good peasants, craftsmen, and traders—and in the cities the workers—go back to their homes and workshops. And their misery or happiness is what awaits them there: sick or healthy children, quarrelsome or agreeable wives, prompt or dilatory customers, pressing or easy-going creditors, a good or bad supper, a clean or squalid bed.”

The characters in Roth’s own fiction may be sentient but are rarely sapient. Never heroic, they are more acted upon than acting. Consider the opening paragraph of Job: The Story of a Simple Man:

Many years ago there lived in Zuchnow a man named Mendel Singer. He was pious, God-fearing and ordinary, an entirely everyday Jew. He practiced the modest profession of a teacher. In his house, which consisted of only a roomy kitchen, he imparted to children knowledge of the Bible. He taught with genuine enthusiasm but not notable success. Hundreds of thousands before him had lived and taught as he did.

Like the biblical Job, Mendel Singer’s essential decency is repaid with relentless sorrow. His two sons are unruly, and one goes off eagerly to join the tsar’s army; he has a daughter who is arranging trysts with Cossacks and who will later, when the family emigrates to America, descend into insanity; a wife whose regard for him is dwindling and who will die an early death; and, worst of all, a last-born son, Menuchim, deformed in figure and barely able to speak. Mendel Singer did nothing to deserve any of this, but must somehow cope with all of it. “All these years I have loved God,” Mendel thinks, “and He has hated me.”

The only flaw in Roth’s Job is the uplifting reversal of fortune on which the novel ends. In the realm of plot, the art of fiction consists in making the unpredictable plausible. In this one novel of Roth’s, alas, the predictable seems implausible. Forgive my blasphemy, but I have never been much convinced by the ending of the biblical version of Job either. Yet, as with the biblical story, so with Roth’s novel, the (relatively) happy ending merely soils but does not spoil the story.

Roth’s next book, The Radetzky March, embodies his central ideas about the human condition: that we are at the whim of happenstance, our fate despite what more romantic novelists might hold not finally in our own hands, with ours not to reason why but to live out our days with what dignity we might manage and then die.

What is surprising is the drama that such dark notions of character can evoke in Joseph Roth’s skillful hands. The Radetzky March is a family chronicle, recording three generations of a Slovenian peasant family, the Trottas, whose rise begins with a son, serving in the Austro-Hungarian army, who one day, almost as much by accident as through bravery, takes a bullet intended for the emperor. He is immediately raised in rank, known in the textbooks as “the Hero of Solferino,” and his family, henceforth allowed to call itself the von Trottas, ennobled. The novel centers on the lives of the son and grandson of the Hero of Solferino.

The son, though wishing for a military career like his father, instead, at his father’s order, becomes a midlevel bureaucrat, serving out his life as a district commissioner in Moravia. Dutiful, punctilious, a man with no vices apart from the want of imagination, District Commissioner von Trotta not only thinks of himself as the son of the Hero of Solferino, but raises his son in that tradition. “You are the grandson of the Hero of Solferino,” he tells him. “So long as you bear that in mind nothing will go wrong.” But everything does. The boy, Carl Joseph, is unfit for the cavalry, for the military, for life generally. He dies a useless death in the First World War fighting for a lost cause that will mark the end of the very world in which he was brought up to believe.

One of the signs of mastery in a novelist is his skill at making his subsidiary characters quite as rich and fascinating as his main characters. In The Radetzky March, the Jewish Army surgeon Max Demant and Count Chojnicki are two such characters. Count Chojnicki is “forty years old but of no discernible age.” Nor is he of a discernible country, for, as Roth writes in another place, “he was a man beyond nationality and therefore an aristocrat in the true sense.” Everything Chojnicki says in the novel is of interest, and it is he, the count, who predicts the fall of the Austro-Habsburg Empire well in advance of the actual event: “This empire’s had it. As soon as the emperor says good night, we’ll break up into a hundred pieces.”

The emperor, Franz Joseph himself, shows up in the pages of The Radetzky March, once to inspect Carl Joseph’s battalion, late in the novel to meet with Carl Joseph’s father, the district commissioner. The emperor is also given a chapter to himself, a brilliant chapter, in which he gauges his own position as a leader thought near to a god even as his mental powers are slipping. Roth assigns the emperor, while inspecting the troops, “a crystalline drop that appeared at the end of his nose” and “finally fell into the thick silver mustache, and there disappeared from view,” thus in a simple detail rendering him human. (Roth’s portrait of Franz Joseph is reminiscent of Tolstoy’s of Napoleon in War and Peace and Solzhenitsyn’s of Stalin in The First Circle.) Herr von Trotta and the emperor die on the same day, and “the vultures were already circling above the Habsburg double eagle, its fraternal foes.”

In Michael Hofmann’s translator’s introduction, he refers, percipiently, to The Radetzky March as a work that “seems to have been done in oils.” What gives the novel that done-in-oil aspect is its weight, its seriousness, ultimately its gravity. No better introduction, for the student of literature or of history, is available for an understanding of the Austro-Habsburg Empire than this splendid novel, written by a small Galician Jew, who came of age in its shadow, grieved over its demise, and owes to it his permanent place in the august, millennia-long enterprise known with a capital L as Literature.

excuse me, “risible”. why should I be the only one to have the fun of having to look everything up?

@ Sebastien Zorn:

However, politics aside, I frankly find the notion that the bible is some sort of universal proclamation rather than simply the history of MY people that everybody else inexplicably decided they wanted to empathize with and make their own is frankly laughable. Well, I guess, I can understand that sort of. I often get bored watching, reading, or listening to non-Asian (Asian includes India, Nepal, Bhutan) but excludes Pakistan and Bangladesh) movies, tv or music, novels, and autobiographies, these days. I guess the grass is always greener.

@ Michael S:

Uhhh, no the Hopi legend was, if you recall, that after our ancestors ruined Mars, the Great Spirit (God) divided humanity into races distinguished by color, one for each continent to be caretaker for that continent. I’m not big on belief. For me, spirituality is a private thing and is completely about what you would think of “gnosis” through meditation. I was just evaluating the evidence for each one’s claim to be prophetic.

As for ethnocentric and xenophobic. Well, when not under attack, I am actually a typical New Age, ecumenical universalist. But, under attack, I pride myself on having become a rabid JEWISH NATIONAL CHAUVINIST (I forgot that epithet earlier, we didn’t use “racist” quite so much back in the day, like I said, I’m rusty.)

And in the words of head of military intelligence, Maxwell Smart, “And Loving it!”

Hello, Sebastien. You said,

“The sin of Babylon, as with all the others then and now, was the persecution of the Jews”

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen such an ethnocentric, xenophobic remark! Your remark is a side-track from the main discussion; but it cannot go unnoticed. Let me respond, that if persecuting the Jews is the world’s greatest sin, then the God of Israel is the world’s greatest sinner! You can bet that I do not agree with this.

As I said, this is a side-track. My interest in all we’ve been discussing, is not to discover who’s been sinning more and who’s been sinning less in the world. My interest is academic, to make sense of the events around us and to see where we’re heading.

America will lead a UN attack on Israel, just as Zechariah 14 says it will. This must needs come some time AFTER Turkey attacks Israel and is defeated (Ezek. 38-39). Everyone will get their turn, and everyone will get to play the game. The end will be a worldwide nuclear war — again, as per. Zech. 14.

Of course, some seem to think that Ezek. and Zech. are in the New Testament. That’s unfortunate for them.

I know you don’t take much stock in Bible prophecies in general, and even seem to put them on the level of Hopi legends. I have just been thinking about this. You know, If my forefathers had paid attention to Hopi legends, they might not have conquered America. Just think! We would all be huddled around the Hudson River, and your neighbors would all be my Dutch, Huguenot and Yankee kinsmen. 300-some million of us, all squashed together around New York City, so the Hopis could gather acorns in peace (Well, not quite — they would be continually fighting the Apache, Navaho and Utes, etc.). What would the population of New York City be then? 50 million? That wouldn’t be bad, would it? As Mike Hogan said, playing Crocodile Dundee,

“With so many people all living in the same place, they must be some of the most friendly people in the world!” Maybe I can move in with you for a few months, just to give you a feel for it. 🙂

@ Michael S:

The sin of Babylon, as with all the others then and now, was the persecution of the Jews. America hardly qualifies. The EU does though. In spades. Pardon me, that Shithole the EU.

@ Sebastien Zorn:

Hello, Sebastien.

You do yourself a great disservice, belittling the scriptures. You are correct about the symbolism of Daniel. It, like that of Ezekiel and the book of Revelation are all taken from pagan motifs. Even the design of the Temple, with its chruvim (similar to the Egyptian and Assyrian sphynxes, all of them “guardian spirits”), uses the same symbolic language as that used in pagan temples.

OF COURSE the number “666” only appears in the New Testament. It is the Hebrew gematria of the Greek spelling of “Nero Caesar”. John was already exiled to Patmos by the Roman Caesar; so it would have been impolitic to flat-out identify the “beast” of his day with Rome. Nero was particularly recalled, because he was the most horrible caesar of both the Christians (whom he burned as human torches) and the Jews (who began the great rebellion against him that ultimately was put down without mercy).

The author of the OP has provided us with the very symbolism of the Book of Revelation, in the Austro-Hungarian coat of arms. The Austrians considered themselves to be the heirs of the Holy Roman Empire (as has the Russians and others before them). The imagery is taken almost exactly from Rev. 17. The angelic figure represents, it would seem, the “holy” part of the “Holy Roman Empire”. I think it also curiously refers to the woman of that chapter, “Babylon the Great, Mother of Harlots”, both of which are embodied in the Pope.

The creature on the left is a griffin, similar to the double-headed griffin in the Byzantine and Russian coats of arms. More generally, it is a chimera, a complex creature made up of other creatures. The eagle and lion, of which the griffin is composed, are two of the creatures mentioned in Daniel:

Daniel 7:

[3] And four great beasts came up from the sea, diverse one from another.

[4] The first was like a lion, and had eagle’s wings

You said you thought the EU might be the successor of the HRE and of Austria-Hungary. This is a widely held view:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Rome

The old US embassy in London also sports a prominent eagle:

https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/6eed9473000e306e27871e9a62830819c17fe35d/0_111_2696_1618/master/2696.jpg?w=300&q=55&auto=format&usm=12&fit=max&s=4a70c8038e0e2ae4c15570c55f6333be

This is all imagery from ancient Rome, identifying us as the “New Rome”.

Revelation likens Rome to the “New Babylon”, and John locates it in the “wilderness”, a code name for the exile, or diaspora. In his day, the diaspora was mainly in the Roman Empire. During the time of the HRE, it moved largely to Poland-Lithuania and Russia; but since WWII, it has been centered in the US. That, I believe, is why the revelator says,

“Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins”

John was Jewish, and he ALWAYS identified the Jews as “God’s chosen”.

Shalom shalom

@ Sebastien Zorn:

Sebastien, maybe you read “The Sacred Mushroom And The Cross”. written by John Allegro. He had the same idea as your pal, and wrote a very convincing book on it. I have it and several others of his. He writes in a fashion to keep maximum interest for the reader. Unfortunately the Sacred Mushroom book caused such a row that it ruined him as a serious scholar…jumped on by his former friends, something the way Velikovsky was scoriated by his contemporaries who tried everything to prevent him publishing..

@ Edgar G.:

Yeah, well all of those other territories that are now states were part of Hungary before Hungary was swallowed by first Turkey and then Austria. Michael S. referred to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Austria-Hungary only existed from the 1860s until its demise in WWI. Vienna made a pact with the Hungarian nobility after 20 years of ruthless oppression following the crushing of the revolution of 1848. Before that it was just the Austrian empire.

Technically you are right, though.

“The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at Austerlitz (see Treaty of Pressburg).”

It’s all relative. History doesn’t really repeat.

@ Sebastien Zorn:

@ Sebastien Zorn:

I’d think that the Napoleonic Empire was the de facto successor to the Holy Roman Empire. Boney destroyed it, and was the overlord of those territories. The later Austro-Hungarian Empire after a frw wars wich it lost, was a few parts of the HRE gathered together under a tenuous unity, which is why Franz Josef was Emperor of Austria and a few other states in the Balkans, but King of Hungary,

The Radetsky March must have been a favorite book of my fathers. Towards the end of his life, as his memory was failing, he gave it to me for my birthday, three years in a row. I remember when I was a kid, his favorite novel was “Revolt of the Angels” by Anatole France.

By the way, if you like this kind of fantasy, I just saw one of the most fun movies I have seen in a long time in a theater. Beats Star Wars or any of the others hands down. I am going to see it again. It’s a Chinese film that just came out called, “Hanson and the Beast”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYjvyhd_CLU

@ Michael S:

This interpretation makes more sense to me:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_7

666 is in the Book of Revelations in the New Testament which only Christians accept as part of the Bible.

I knew a guy from Patmos who was convinced John was out of his gourd on mushrooms when he wrote it.

@ Edgar G.:

This guy actually, I kid you not, says that Trump intended to lose just so he could be more famous and make a lot of money, that his play book was Mel Brooks’ “The Producers”!

Wolff says, Trump assured his wife and everybody around him not to worry, no chance of his winning! The book is a complete fake news hatchet smear job by a a typical anti-Trump progressive hack who recycles all the old dem libels, corrupt, incompetent, immoral, blah, blah, blah.

It’s worth noting that President Trump has threatened to sue Wolff for slander but to sue Bannon not for slander — he believes him then — but for violating a confidentiality agreement he had signed in which he also promised not to publicly criticize the administration, in other words, he had no business being interviewed about his experience in the White House in the first place.

@ Sebastien Zorn:

“So, I guess, the EU is the closest thing to a successor state.”

Some guess that way; I don’t. The way I see it, the successor states to the HRE (namely, the colonial powers) pretty much bit the dust at the end of WWII. There is a prophecy concerning them:

Daniel 7

[7] After this I saw in the night visions, and behold a fourth beast, dreadful and terrible, and strong exceedingly; and it had great iron teeth: it devoured and brake in pieces, and stamped the residue with the feet of it: and it was diverse from all the beasts that were before it; and it had ten horns.

[8] I considered the horns, and, behold, there came up among them another little horn, before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots: and, behold, in this horn were eyes like the eyes of man, and a mouth speaking great things.

[9] I beheld till the thrones were cast down, and the Ancient of days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire.

[10] A fiery stream issued and came forth from before him: thousand thousands ministered unto him, and ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him: the judgment was set, and the books were opened.

[11] I beheld then because of the voice of the great words which the horn spake: I beheld even till the beast was slain, and his body destroyed, and given to the burning flame.

For Edgar’s sake, a tutorial: This was written by Daniel, who lived in the Sixth Century BCE

We’re looking for “a mouth speaking great things” — probably an American, by the context. Sebastien, you can feel comfortable in knowing the this probably is not 666Jared Kushner666, who hardly ever speaks.

The jury’s still out on that one.

@ Sebastien Zorn:

Bannon says he was misquoted and also taken out of context. Hard to believe that such a smart man could say such things to a third class writer. Maybe he got him fershickert and had a pocket recorder.

@ Sebastien Zorn:

That’s the best laugh I’ve had this week, since I saw a Laurel and Hardy picture. They are always my favourites since childhood. This one was “Way out West” ..hilarious.

Charlie, or should I say Chayim, sounds as if he came from the shtetl next door to the one where my dear late father was born, a Litvak, because in those days, Lithuania also included Latvia and a lot more, even joining with Poland for a couple of hundred years. It at one time was spread right across Eastern Europe from the Baltic nearly all the way down to the Black Sea.

That “Ewwwww” must have been at the brit..

@ Edgar G.:

Are you familiar with the British contribution to Charlemagne’s ascension to power?

Charlemagne gathered all the warring parties around a big round table that he had bought from a total liquidation fire sale at Camelot, and he said to them:

“Look, you may think I ‘ave alota Gaul but lemme be Frank, less not fight nomore, less all be Friendzhe*. And so zey were.

* That early spelling constitutes the Portugese/Polish contribution, and so you see the antecedents of pretty much the whole EU, more properly pronounced, “Ewwwww.”** I’ll take that cloth, now, thanks.

** https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=eww

Speaking of which, I just started listening to “Fire and Fury” as an audio book on Scribd. It sounds completely made up. Has anybody actually asked Bannon he if he really said anything this character attributed to him, I wonder?

@ Sebastien Zorn:

To make a long story short, Charlemagne was considered the first Holy Roman Emperor in about 800, after having been crowned by one of the Popes.

I believe that one of the countries which has been overlooked was called -a little irreverently it seems – “Holy Smoke”…. Maybe it was the piece of paper burnt at a wall opening to signify to the watchers, when a new pope is chosen. It could be called “holy smoke”… Maybe the surreptitious puffs at cigarettes that some popes indulged in.

@ Michael S:

Which countries were part of the Holy Roman Empire?

HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE. The Holy Roman Empire was a feudal monarchy that encompassed present-day Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech and Slovak Republics, as well as parts of eastern France, northern Italy, Slovenia, and western Poland at the start of the early modern centuries.

Austria-Hungary was the successor state of the Holy Roman Empire, much in the way that Russia has succeeded the Soviet Union. Napoleon brought about the formal end of the HRE in 1804. In 1815, it was replaced by the German Confederation, led by Austria and Prussia. In 1848, Prussia withdrew and, over the next 18 years, absorbed most of the old empire except the Habsburg dominions. After 1918, Austria-Hungary fell apart; and in 1838, Hitler swallowed up what was left. This was the end of an empire, the alleged successor to the Western Roman Empire, which had lasted from its de facto inception in 750 AD — a lifetime of over 1000 years. ALL the major ruling houses of Europe come from dynasties originating in the HRE, from the Bourbons of France and Spain, to the Wettins (now called “Windsor”) of the UK, to the Hohenzollerns to the Oldenbergers of Scandanavia and Russia to the Savoyards of Italy.

Poof! It’s gone. Like the ten horns of the beast in the Book of Daniel, the HRE was superseded by the Great Colonial Powers; and since the end of WWII, it has been replaced by the US — which is the most powerful empire in history. We will also disappear.