Behind the palace intrigue between Abdullah and his half-brother are real frustrations among Jordanians toward a regime that Jerusalem sees as a key security bulwark

By LAZAR BERMAN, TOI 8 April 2021,

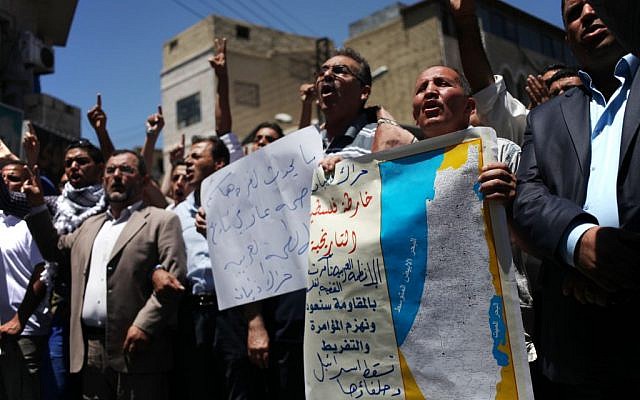

Jordanian security forces stand on guard as protesters wave Jordanian flags and chant slogans during a demonstration near the Israeli embassy in the capital Amman on July 28, 2017. (AFP Photo/Khalil Mazraawi)

Jordan has been gripped by rare palace intrigue since King Abdullah’s half-brother Prince Hamzah was placed under house arrest on Saturday, accused of plotting a coup.

The dramatic and very public episode — which appears to be drawing to a close — is a potential source of significant concern for Israel, which considers the stability of the Hashemite kingdom a central plank of its national security doctrine.

Since its founding, Israel has had some level of security cooperation with Jordan. In the days before the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Jordan’s King Hussein met secretly with Prime Minister Golda Meir near Tel Aviv to warn her about the impending Arab invasion. Cooperation ramped up following the 1994 peace treaty between the sides, and though diplomatic ties are often frayed, the military relationship has been especially close over the decades, with Israeli and Jordanian jets even driving Russian planes in Syria away from their borders together in 2016 in a firm show of resolve.

Israel views Jordan as a reliable buffer against hostile states to the east — once Iraq, now Iran. Israel’s border with Jordan, and the Israel-controlled frontier between the West Bank and Jordan, has remained an oasis of quiet even as Iran’s armed proxies entrench themselves from Baghdad to Beirut, and jihadist groups grow in the Sinai.

A weakened regime in Amman could create a power vacuum that would allow terrorist groups to establish a foothold all along Jordan’s border with Israel and the West Bank. Palestinian refugees in Jordan could inspire dangerous unrest in the West Bank, and far more radical elements could replace the Jordan-funded Islamic Waqf on the Temple Mount. Iran would also likely seek to take advantage of the chaos to open a new front against Israel.

Hamzah is not about to lead a coup that destabilizes Jordan, certainly not without the support of significant parts of the military. But behind the unfolding drama are real frustrations in Jordanian society that, if they continue to grow, could threaten the foundations of Abdullah’s regime.

Jordanians take part in a protest after the Friday prayer in the capital Amman, on February 24, 2017 against the government’s decision to impose new taxes on a string of goods and services, calling on the cabinet to resign. (AFP/ Khalil MAZRAAWI)

“It’s a little bit more than just the frustration of the prince, but much less than an attempt at a coup,” said Oded Eran, a senior researcher at Tel Aviv’s Institute for National Security Studies and a former Israeli ambassador to Jordan.

Frustration in Jordan has simmered for years against the background of economic troubles, political repression and doubts about Abdullah’s legitimacy. In the last year, the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated many of the public’s grievances, albeit mostly within the confines of the monarchy’s tight control of free expression.

Though support for the monarch remains strong, the fissures have the potential to cause the entire edifice of the Hashemite regime to crumble, with deleterious effects for Israel and its security.

Half-brothers and full rivals

The royal drama playing out in Amman is rooted in the longstanding rivalry between Abdullah and Hamzah.

Jordan’s then Crown Prince Hamzah, left, with his mother Queen Noor, right, during his wedding ceremony in Amman, Jordan, May 27, 2004. (Hussein Malla/AP)

Only a week before his death in 1999, Jordan’s King Hussein dramatically stripped his brother Hassan of the title of crown prince, which he had held for 36 years. Instead, Hussein’s son Abdullah, then a general in the Jordanian military, was made heir to the kingdom.

But on his deathbed, Hussein also instructed Abdullah, whose mother was Hussein’s second wife Muna, to name Hamzah, born 18 years earlier to his fourth and final wife Noor, as crown prince.

“[Hamzah] is said to have been Hussein’s favorite son,” wrote the Los Angeles Times just after Hussein’s death. “Many Jordanians believe that Hamzeh, as a result of Noor’s considerable influence, would have been chosen instead of Abdullah were it not for his age.”

Jordan’s King Abdullah II (left) laughs with his brother, then-crown prince Hamzah (right), on April 2, 2001, shortly before the Jordanian monarch embarked on a tour of the United States. (AP Photo/ Yousef Allan/File)

Abdullah initially honored his father’s wish and named his half-brother crown prince, but from the moment he took the throne, many expected that he would eventually chart a different course.

“Abdullah will never be able to quell suspicions that he will do to Hamzah what Hussein did to Hassan—that is, appoint his own son as successor instead of his brother,” wrote Robert Satloff of The Washington Institute in April 1999.

Only five years into his rule, Abdullah made his move. After appearing at Eid al-Fitr prayers at the end of Ramadan with his 10-year-old son Hussein at his side instead of Hamzah, the king convened a meeting of the royal family at which he stripped Hamzah, then 23, of his title.

The rivalry, which has reverberated through the royal family, has become wrapped up with a chunk of doubt regarding Abdullah’s legitimacy as king of Jordan.

His mother is the very English Toni Avril Gardiner, a convert to Islam who changed her name when she married Abdullah.

Abdullah himself spent the bulk of his formative years in the United Kingdom and the United States, attending Deerfield Academy, Sandhurst, Oxford University and Georgetown University. While his English is impeccable, his Arabic during the early years of his reign was described as imperfect.

FILE: Jordan’s King Abdullah II, right, and his brothers, Prince Faisal, center, and Prince Hamzah, left, stand together during the national anthem at the opening of a royal luncheon at the Royal palace compound in Amman, Jordan, in this May 26, 2004, file photo, marking state celebrations for Hamzah’s wedding. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Such a pedigree was problematic for the head of the Hashemites, which is the oldest dynasty in the Muslim world, and claims direct lineage from Muhammad.

“Hamzah’s mother was born Muslim, and therefore Hamzah is a more authentic Muslim than the king” in the eyes of many Jordanians, said a Middle East scholar who asked not to be named.

Many Jordanians frustrated with the regime’s policies have lined up behind Hamzah and may see the moves to sideline him under the pretext of an alleged coup as an attempt to marginalize their concerns.

“All along, among certain tribal circles, certain east Jordanian circles, there’s been this undercurrent that Hamzah’s been done [wrong],” said Joshua Krasna, a fellow at the Moshe Dayan Center at Tel Aviv University, referring to nationalist East Bank Jordanians.

Abdullah’s marriage to Rania, whose parents are Palestinian, has done little to endear him to the East Bankers, who are cognizant of the rising clout of urban Palestinian businessmen as Jordan liberalizes its economy, and eternally wary of their country becoming the Palestinians’ “alternative homeland.” East Bank Jordanians have chanted at soccer matches, “Divorce her you father of Hussein, and we’ll marry you to two of our own.”

While direct criticism of the king is illegal in Jordan, the queen has been denounced as corrupt and wielding undue influence. While some of the opprobrium is indeed aimed at the queen herself, at least part of it is regarded as actually directed toward the king or royal family.

In combination with sagging — but still strong — support for Abdullah, Hamzah’s displeasure at being kept out of the halls of power drove his public and private criticism of the king, but observers don’t think the former crown prince was trying to topple his half-brother.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II and Crown Prince Hussein (R) arrive for the opening parliamentary session in the capital Amman on November 10, 2019. (Khalil Mazraawi/AFP)

Hamzah’s popularity and criticism on social media was “making him a nuisance to the king who is prepping his son Hussein to take over sometime in the future,” explained a Jordan-based journalist who requested anonymity.

Many critics of the regime — for reasons of both legitimacy and corruption — increasingly back Hamzah. “He enjoys popularity among East Bank Jordanians,” said the Jordanian journalist, “and his popularity has shot up in recent years as the country faced critical economic and social challenges amid allegations of corruption at the highest level. This latest episode, regardless of the veracity of accusations, has polarized Jordanians with many showing further sympathy for him.”

Tribal tribulations

The tribal groups that have traditionally been seen as the bedrock of regime support have been increasingly critical of not only the government in recent years, but of the entire ruling system.

Tribal support for the monarchy has never been as solid as it is often described. The relationship has always been largely transactional, with the regime offering patronage jobs and services in exchange for political support. The alliance occasionally sees ruptures, as it did during massive 1989 protests against rising fuel prices that resulted in political reforms.

In 2011, at the start of the Arab Spring, dozens of organizations of young tribal activists coalesced into the Hirak movement. Instead of economic demands, as most tribal protests had focused on in the past, the Hirak demonstrations were explicitly about democratic change. They wanted new election laws and an end to corruption, and many even called for regime change, adopting revolutionary slogans used in countries where Arab autocrats were deposed that year.

Hirak protesters not only discussed whether Abdullah should step down, they also debated changing succession laws so that Hamzah could replace him instead of crown prince Hussein.

Unlike the Islamist and leftist groups that have traditionally made up what little political opposition the regime allows as a pressure valve, Abdullah severely cracked down on the Hirakis, a sign that Amman viewed them as a real threat.

Jordanians take part in a protest after the Friday prayer in the capital Amman, on February 24, 2017, against the government’s decision to impose new taxes on a string of goods and services, calling on the cabinet to resign. (AFP/Khalil Mazraawi)

“In the absence of powerful political parties, they now emerge as the real opposition, and that is why they have been targeted by the state with many being held without trial,” the Jordanian journalist said.

Islamists in the kingdom — especially the Muslim Brotherhood and its political arm, the Islamic Action Front — represent the mainstream opposition, and had a tacit understanding with the regime on the limits of their activities over the years. This has changed recently, as the regime declared the organization illegal in 2014 and confiscated property.

The Hirak movement presents “a far greater threat than Islamist protesters,” Temple professor Sean L. Yom wrote in 2014, “because it delivered uncontrolled and raucous opposition from the heart of a tribal countryside historically allied with the crown.”

Jordanian protesters argue with members of the gendarmerie and security forces during a demonstration outside the Prime Minister’s office in the capital Amman late on June 2, 2018. (AFP PHOTO / Khalil MAZRAAWI)

The Jordanian journalist noted that Hussein had recently begun trying to emulate Hamzah by visiting tribal areas, seeking to shore up his support among key groups.

Sidelining “Hamzah now is thought to make it easier for the crown prince to take over from his father,” the journalist said.

Pandemic politics

The COVID-19 pandemic has only intensified discontent in the kingdom.

Jordan’s strict lockdown was initially effective in slowing the spread of the virus, but it wreaked havoc on the economy. Unemployment reached nearly 25% by the end of 2020, as the economy suffered its worst contraction in decades.

Amman’s empty Roman Theater on March 18, 2020, as Jordan takes measures to fight the spread of the coronavirus COVID-19. (Khalil Mazraawi/AFP)

The Hamzah affair “comes on the background of a deteriorating economic situation,” said Eran. “One of the main sources of income is tourism, and tourism totally stopped, plus the lockdown. The prices of basic staples are going up.”

To compound challenges, Ramadan begins next week, and demand for basic foodstuffs will rise significantly.

“Economic challenges, especially under the pandemic, have given a new drive for the Hirakis who are becoming more vociferous in their criticism, especially on social media,” said the Jordanian journalist.

Jordan’s handling of the health crisis is also coming under fire. The number of deaths has spiked in the past month, reaching around 100 a day, and the government has had to fend off rumors of vaccine supply issues.

In March, a number of COVID patients died in a Jordanian hospital when the facility ran out of oxygen. The incident sparked angry demonstrations, resulting in the resignations of the kingdom’s health minister and the director of the hospital.

“There are large pockets of frustration, even protests against the current situation, and the handling of the situation by the government,” explained Eran.

Jordanian security forces stand guard around a chalk Star of David drawn in a street bearing the words “Trump” and “Israel” in Arabic, during a protest against US President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, in the Jordanian capital Amman on December 15, 2017. (AFP/Khalil MAZRAAWI)

The episode in Jordan comes as ties between Amman and Jerusalem have become increasingly frayed, with many of Abdullah’s anti-Israel moves viewed through the lens of the king attempting to deflect criticism or ease pressure on the monarchy.

Abdullah said in 2019 that relations between Israel and Jordan were “at an all-time low” after a series of incidents that prompted Amman to recall its ambassador to Israel.

Things appeared to sink even lower last month, when years of Jordanian frustration with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu boiled over as officials in Amman appeared to accuse him of endangering the region for political reasons and alleged that Israel had violated agreements with them.

The pointed comments from Jordan’s foreign minister came the day after Crown Prince Hussein abruptly canceled a planned visit to the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem over a disagreement with Israeli authorities about his security detail. Jordan retaliated by delaying approval for the prime minister’s flight path over the country to the United Arab Emirates for a planned visit that was ultimately scrapped.

Netanyahu may have also used Jordan as a punching bag to shore up support on the right. Aides to the prime minister attacked Jordan in Haaretz last month, calling it a country in decline that is increasingly dependent on Israel. Netanyahu also reportedly delayed approving a request from Jordan for water aid last week.

Defense Minister Benny Gantz speaking at Channel 12’s Influencers Conference on March 7, 2021. (Sindel/Flash90)

The Jordanian journalist noted that Defense Minister Benny Gantz had recently said Israel was prepared to assist Jordan as necessary, in the first official comments from Jerusalem about the alleged coup attempt.

“It is hoped that a new government will be more appreciative of Jordan’s importance as a neighbor and a partner,” said the journalist. “Already we heard Benny Gantz’s comment on Jordan’s stability but your [prime minister] remains silent.”

In the past, Abdullah has managed to deftly disarm opposition by appearing to take the complaints seriously.

In the wake of the 2011 protests, the king adopted the rhetoric of political change, but critics called the reforms cosmetic. By 2016, Abdullah had shepherded through constitutional reforms that concentrated even more power in the hands of the monarchy, and also cracked down on the previously tolerated Islamist opposition as well as the Hirakis.

Protesters chant slogans against Israel to condemn its bombing of Gaza and demanding Hamas and other Palestinian brigades in Gaza reject any truce with Israel, during a protest by followers of the Muslim Brotherhood in Amman, Jordan, Friday, July 18, 2014 (AP/Mohammad Hannon)

Recently, Abdullah has sought to tamp down on growing discontent by disavowing nepotism and corruption, and appearing to back a rethink of the country’s political system.

“Our goal for many years has been to reach a platform-based political party scene that reflects the ideology and leanings of Jordanians, and carries forward their concerns and national causes, and works towards achieving their aspirations by conveying their voices and bringing their representatives to Parliament,” he said in January.

But many Jordanians are not buying his rhetoric.

“This is being met with a little bit of cynicism,” said Krasna, “because this is how he always reacts.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.