Zeev Elkin wants to divide Jerusalem and create an Israeli municipality for Palestinians in several neighborhoods situated beyond the separation barrier in the city

By Jonathan Lis and Nir Hasson, HAARETZ

Jerusalem Affairs Minister Zeev Elkin has unveiled his proposal for the municipal division of Jerusalem, which would see several Arab neighborhoods beyond the West Bank separation barrier split off from the Jerusalem municipality and be placed under the jurisdiction of one or more new council administrations.

The move will require the approval of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the completion of various legislative amendments, whose first reading was already passed by the Knesset in July.

Elkin said he believed his plan, which he intends to promote in the coming weeks, will not face serious resistance from either the right or left.

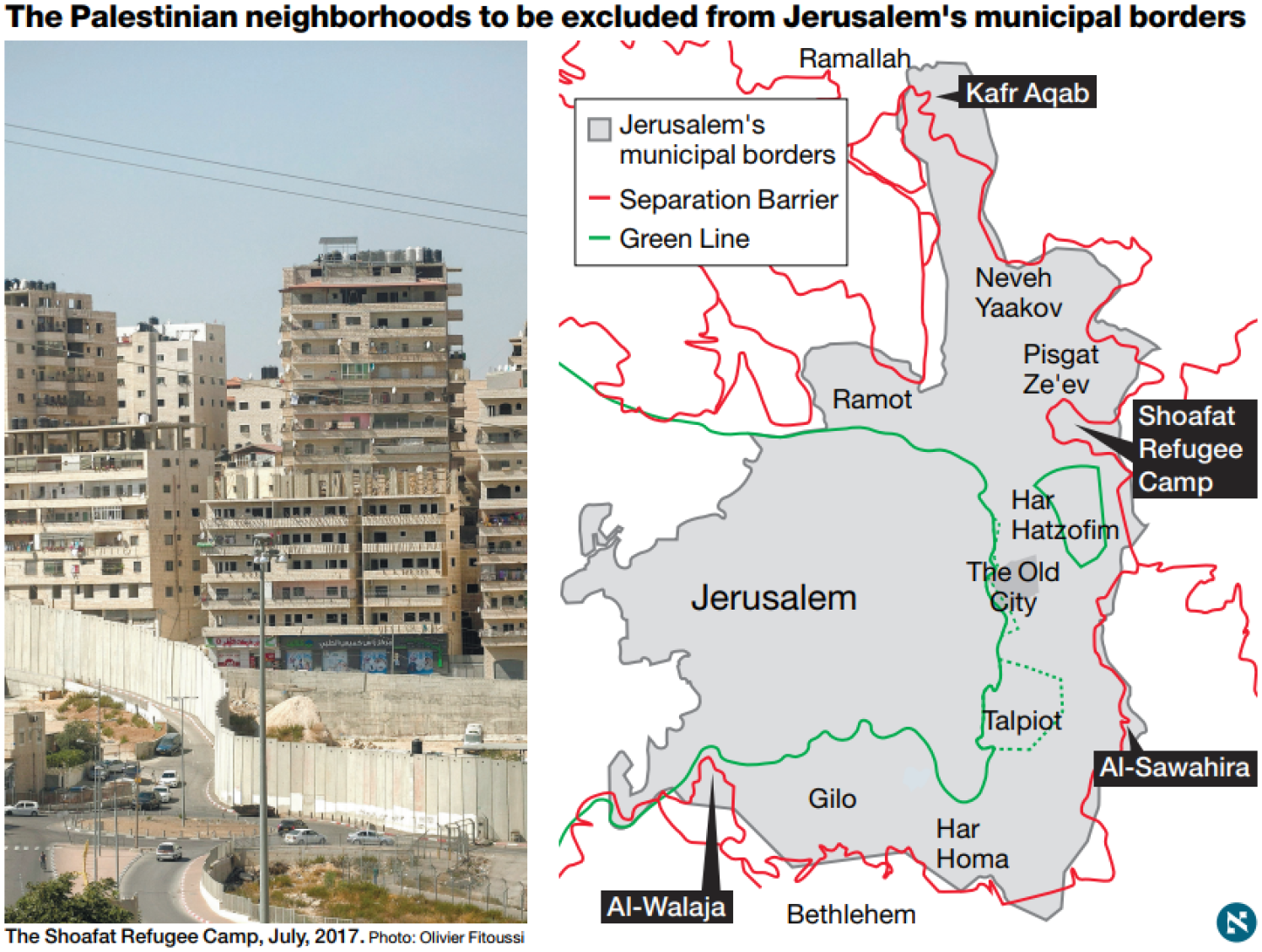

The neighborhoods that would be excluded from Jerusalem’s municipal borders under the bill.

This is the first attempt to reduce the municipal area of Jerusalem since it was expanded after the Six-Day War in 1967. It is also the first attempt to establish an extraordinary Israeli local council whose inhabitants are not Israeli citizens, but rather Palestinians with the status of permanent residents only.

The neighborhoods beyond the separation barrier are the Shoafat refugee camp and a neighborhood adjacent to it in northeast Jerusalem, Kafr Aqab, as well as Walajah, in the southern part of the city, and a small part of the neighborhood of Sawahra.

No one knows precisely how many people live in these areas. The figure is estimated at between 100,000 and 150,000, one-third to one-half of whom have Israeli identity cards and residency status. Since the construction of the separation barrier some 13 years ago (the barrier at Walajah is currently being completed), these areas have been cut off from Jerusalem, though they still come under the capital’s jurisdiction.

Following construction of the barrier, the Jerusalem Municipality, police and other Israeli agencies stopped providing services in these areas. Anarchy reigned in the near-absence of police and construction inspectors, with very serious infrastructure problems. Tens of thousands of housing units were constructed without permits, and crime organizations and drug dealers have proliferated.

“The current system has completely failed,” Elkin said. “The moment they routed the barrier the way they did, it was a mistake. But at the moment, there are two municipal areas – Jerusalem and these neighborhoods, and the connection between them is very loose.

Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage Minister Zeev Elkin with Culture Minister Miri Regev, June 2017.Yonatan Sindel/Flash90

“The army can’t formally act there, the police go in only for operations, and the area has become a no-man’s-land,” he added. “Providing services of any kind has become dangerous, and tall buildings and such high density as this can’t even be seen in Tel Aviv.”

Elkin also cited the danger that the buildings could collapse in an earthquake.

However, these are not the only problems worrying Elkin. He is also concerned with the rapid demographic growth in these areas, and its impact on the balance between Jews and Arabs in Jerusalem.

Many of the families in these neighborhoods consist of one parent who is an Israeli resident, and therefore the children are Israeli residents – which increases the number of Palestinian residents in Jerusalem.

According to Elkin, cheap housing, proximity to Jerusalem and the lawlessness prevailing there have made these neighborhoods a magnet for people from Jerusalem and the West Bank. “There are also dramatic impacts in terms of the Jewish majority and because you can’t improve the standard of living there, because we expect [the population] will continue to grow,” Elkin said.

The minister added: “Precisely because I believe in their electoral right and I want them to use it, I cannot be indifferent to the danger of the loss of a Jewish majority that is caused not by natural processes, but by illegal migration into the State of Israel that there is no way for me to prevent.”

Elkin said various solutions had previously been examined in order to tackle the problem. In terms of security and ideologically, the minister said he rejected solutions such as handing the neighborhoods over to the Palestinian Authority. He also rejected changing the route of the separation barrier for security, financial and legal reasons.

The details of Elkin’s plan are not final. It is unclear whether this will be a single regional council without territorial contiguity or two regional councils. So far, the residents have not agreed to hold elections to establish the new municipal entity, and in the initial years it would operate under an administration appointed by the interior minister.

“I have no doubt that for this plan to succeed, cooperation will have to develop with the local leadership,” Elkin said. “Their interest is in changing their intolerable living conditions. It might take time, because there is a lot of mistrust – but it can’t get any worse,” he added. Elkin pledged significant government investment in the neighborhoods.

Elkin has been working on his plan for several months. When Education Minister Naftali Bennett raised his proposal to amend the Basic Law on Jerusalem, Elkin feared if that bill passed in its current form, it would put his own plan at risk – since Bennett’s proposal would prevent a future division of Jerusalem.

To address this issue, Elkin inserted an ambiguous clause into Bennett’s bill: This would make it impossible to give any part of Jerusalem to the PA, but the municipality could be divided into smaller Israeli council entities.

Most of the lawmakers supporting Bennett’s bill did not know they were voting for a bill that might involve splitting off parts of the Jerusalem municipality. But Bennett’s acceptance of the clause allowed the governing coalition to support the bill, and the law passed with the automatic support of most of the coalition.

Elkin said the legislation would be completed in November and would then be presented to Netanyahu. If the prime minister, who is aware of the details of the plan, supports it, it could move ahead quickly. Legally, the plan does not require Knesset legislation, but only a decision by the interior minister.

“This idea is not easy for either the left or the right to accept,” Elkin said. “Each side can see benefits, but on the other hand there are dangers. It’s true that if someone wants to transfer this area [to Palestinian administration], it will be easier to do so,” he added.

In political circles, it is believed that the plan’s main opponent will be Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat, because the municipality stands to lose major funding if it loses administrative control of these neighborhoods. The PA is also expected to oppose the plan, seeing it as an attempt to increase the number of Jews in Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, the coalition is also promoting a plan by MK Yoav Kish (Likud) that would annex – municipally, but not politically – the residents of the settlements situated near the capital under one municipal roof. This would add hundreds of thousands of Jewish voters to the Jerusalem Municipality, and on paper would change the demographic balance of the city.

Although it is on the agenda for the Ministerial Committee for Legislation’s meeting on Sunday, there will be no vote on the bill at the meeting. According to a senior member of the coalition, this is because the bill in its current form “invites international pressure and contains serious legal problems. Netanyahu can’t allow himself to promote this form of the bill at this time.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.