The U.S. generously publicizes joint drills with Israel, while it expects Israel not to take unilateral military action ? On the judicial crisis and calls to refuse duty, Defense Minister Gallant – a minister the U.S. still sees as a partner to dialogue – is both right and wrong

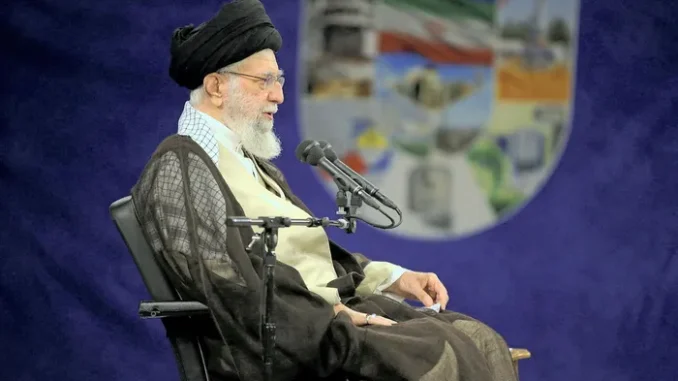

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei during an exhibition of the country’s nuclear industry achievements in Tehran earlier this month.Credit: Wana News Agency / Reuters

Things are going pretty well for Iran these days. The hijab protest has waned, the tightening relations with China and Russia are bearing fruit, and the Arab states, aware of the new international strategic reality, are looking for routes to rapprochement with Tehran. But for the regime there, the crowning glory is likely related to a deal with the United States.

Under the aegis of the Biden administration, the international media are talking about emerging understandings whose aim is de-escalation, a reduction of friction. In practice, what’s shaping up looks more like an unwritten agreement of which a significant portion is already starting to be implemented. The Biden administration is declining to term it officially an agreement, not least because that would stir a negative response by the Republicans in Congress.

‘A Very Combustible Situation’: Israel’s Judicial Coup Is Back Full Force

The U.S. initiative is based on a freeze in return for a release. Iran has committed not to enrich uranium above a level of 60 percent – that is, not to reach the 90-percent level at which nuclear arms can be manufactured. Washington, for its part, has withdrawn its opposition to the release of Iranian assets worth $20 billion in banks across several countries. Iran and Western countries will mutually release prisoners and kidnapping victims. These unofficial understandings have already taken effect, and it looks as though Iran has slowed down, if it hasn’t already stopped, enriching uranium to high levels. The compromise effort is being coordinated by Brett McGurk, the Biden administration’s National Security Council coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa

Concurrently, the Americans sought to place Israel in a kind of bear hug. On the one hand, they are more generous when it comes to official publicity about joint military exercises, which imply joint attack capability against Iran (and it could be they are also willing to discuss this in greater detail in backrooms). On the other hand, their expectation is apparently for Israel not to take them by surprise in the form of an independent attack on Iran. More than a decade ago, the U.S. invested a major effort, both in collecting friendly intelligence and in moves that can be described as “soft influence,” to ensure that no such scenario came to pass. Since then, one basic fact has changed: The Biden administration trusts Netanyahu even less than the administration of Barack Obama did.

The White House is now looking toward a different target date, namely the presidential election in November 2024 (as is Netanyahu, though he’s likely hoping for the opposite result). Until then, the aim is to ensure that things remain on a low burner. With understandings, Iran will not burst through to nuclearization and the likelihood of an Israeli attack is vastly reduced. Washington hopes to use this time to focus on the two principal fronts from its perspective: China and Russia-Ukraine. The primary expectation from Israel is for it not to interfere.

In the meantime, Jerusalem is playing its part. Gallant has thought for some months that the U.S. was aiming to reach understandings with Iran; Netanyahu made do with lip service by way of objecting, but has not actually mounted a concrete campaign against the understandings. The experts say it’s really quite a good idea, considering the alternatives. This way we will at least gain time until Iran next considers breaking through to the bomb, and in the meantime the military option can continue to be developed, after it was neglected for six years – from the signing of the nuclear agreement in 2015 until the rise to power of the government of Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid in 2021.

In security cabinet and regular cabinet meetings on Sunday of this week, Netanyahu was perceptibly on edge about the possibility of mass refusal to serve by reservists. He pressured the attorney general and state prosecutor to find a legal reason to take measures against those who organize for or preach refusal to serve, as he sees it. There is dual sensitivity here: not only because of the regime coup, but because of the Iran issue. During the air force pilots’ protest last March, Netanyahu was incensed by what a reservist pilot said in a Channel 12 interview: “Without us, Netanyahu doesn’t have anyone to attack Iran.” That was the basis for Netanyahu’s attacks on the IDF chief of staff and on the commander of the air force in light of the pilots’ protest. The preparations for Iran, or their semblance, are his chief joy; the air force pilot spoiled the narrative.

‘Oops, too late’

In 2012, at the height of the debate about a possible attack on Iran’s nuclear project, the then-defense minister, Ehud Barak, coined the phrase “immunity zone.” Barak, who at the time, in coordination with Netanyahu, was pressing for an attack on Iran, contrary to the opinion of the heads of the security branches, maintained that only a limited time remained for Israel to bomb Iran before it fortified its subterranean sites in a way that would render an attack ineffective. When the generals argued that the time was not yet ripe for an attack, Barak claimed that a situation might be created of “too soon, too soon … oops, too late.”

That’s also the thinking of many of the leaders of the protest movement, in the wake of the decision by the reservist pilots and navigators not to declare at this stage that they will cease volunteering for service. The concern is that waiting for the picture to become clear will enable Netanyahu to make a snap move and enact the law to cancel the reasonability standard in the final two votes on the bill in Knesset. The pilots prefer to wait until next week. Until then, a critical mass of resignation letters might emerge, which each pilot will write individually. If the total number reaches the red line set by the IDF for the necessary size of qualified air crews, the coalition’s coup legislation and the air force’s fitness will be pitted against each other.

This time, Gallant is on Netanyahu’s side. To people with whom he has spoken, Gallant sounded apologetic, defensive. Unlike other ministers, the defense minister does not declaim the talking points of the Prime Minister’s Office. But of late he has apparently forged an alternative narrative about the protracted political crisis. According to Gallant (and there is truth in this), he was the only one ready to take a courageous step, almost to commit political suicide, and bring about a freeze in the legislation last March. Now, when the opposition could have arrived at a compromise and made do with limited legislation – and perhaps also join the government and thus dictate a more moderate, centrist line – it is unwilling to take this step because of its burning hatred for Netanyahu and the boycott it has imposed on him. In Gallant’s view, refusal to serve is outright unacceptable, and perhaps the protest is exaggerated, he says, because what’s in the cards is only a small part of the originally planned legislation.

The narrative Gallant has fashioned for himself ignores two facts. First, that it was the protesters who kept him in the Defense Ministry in March. If half a million Israelis hadn’t taken to the streets to protest Netanyahu’s attempt to punish Gallant for making his courageous move, his dismissal (reportedly the idea of Netanyahu Jr.) would have gone through. And second, the protest is focused on the hallucinatory situation in which a prime minister who is under severe indictment on corruption charges insists on staying in office, despite his undertakings in the past, and is also trying to exploit his status to crush Israeli democracy.

Together with the pilots’ protest, U.S. pressure against the coup legislation is rising. Hardly a day went by this week on which President Joe Biden, the State Department or commentators close to the administration, such as the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman, didn’t assail the Israeli government’s actions. The Pentagon is continuing to maintain a substantive relationship with Israel’s security establishment, but even there, in the day-to-day conversations, apprehension is being voiced in the light of the rampages by settlers in the territories, and Israelis are plied with questions about the political crisis.

Gallant is perceived by Washington as a minister with whom it’s still possible to hold a dialogue, certainly after the attempt to dismiss him. He lacks independent political clout such as his predecessor, Benny Gantz, wielded, but the Americans are also encouraged by his relatively moderate stance regarding the Palestinians and by the way he and the security chiefs have spoken out against Jewish terrorism in the territories.

The tensions with the administration are directly affecting the IDF’s long-range force building plan. For all kinds of reasons, there has been a delay in the air force’s acquisition of aerial refueling planes, which are considered a critical component in connection with an attack on Iran. This week, as a kind of compensation, the United States sent a refueling aircraft of its own to a joint exercise in Israel, thereby enabling the air force to gain prior experience. The administration is continuing to further the deal for Israel’s procurement of an F-35 squadron, although the differences of opinion about assimilating more Israeli systems in the planes to come remain unresolved.

I am puzzled about the degree to which those in the IDF believe they have a right to refuse orders based upon their political passions. I don’t know the differences between the IDF and US military forces. The one difference I have learned about is that members of the IDF are encouraged to think creatively. But there used to be a standard amongst members of the US military. That standard meant that members of the military were apolitical, and responsible only to the command structure of the military.

I don’t understand how any member of the IDF can threaten a sitting Prime Minister in a newspaper that he and other IDF members will undermine the PM’s attempts to protect national security.

In the US the President is the Commander in Chief, so behavior like that might trigger a Court Martial.

Why is it possible in Israel for members of the military to threaten a duly elected government with refusal to follow orders that are needed to protect national security? Why are these individuals not standing in a military court explaining themselves?

While every individual has a right to their opinions, usually a country’s fighting forces are loyal to and want to protect the country they serve. If a member of the military wants to undermine his/her government, should they not be fired for insubordination? How can a military depend upon individuals who pick and choose which orders they will follow?