As its economy falters and protests continue to rumble, Jordanian activists and tribes are demanding greater representation

Before the 9th century BC, Dhiban was the capital of Mesha, king of Moab.

The Mesha Stele, which was discovered in Dhiban in 1870 by a British archaeological survey, tells the story of how King Mesha defeated the Israelites and freed the lands of Moab from their rule.

According to the Mesha Stele, which currently sits in Paris’s Louvre, the Moabites’ subjugation to the Israelites and their liberation was an act of anger and retribution by Chomesh, their god.

Dhiban lies on mountain hills surrounded by wheat crops and meadows of sheep.

The road to al-Hidan, a well-known valley in Dhiban, passes by the alleged site of Mesha’s castle, ruins that are partly covered by grass and soil.

Wheat crops form the scenery of Dhiban’s countryside (MEE\Mustafa Abu Sneineh)

Wheat crops form the scenery of Dhiban’s countryside (MEE\Mustafa Abu Sneineh)In modern times, Dhiban is famous for being the cradle of Jordan’s “Arab Spring” protests of 2011.

Dhiban’s relentess protests demanding political and economical reforms were a driving force behind the resignations of four prime ministers between 1 February 2011 and 11 October 2012.

Sabry Mashaleh, a Dhiban resident and one of the town’s most prominant protesters, is proud of this history.

When protests erupted in Jordan in June against controversial IMF-backed economic plans, including income tax rises and fuel and electricity fee hikes, he and other residents of his rebellious town rented buses to take them to demonstrations in the Fourth Circle neighbourhood in Amman, where the prime minister’s office is located.

“We have a reputation among the police. Once they heard that Dhiban’s buses arrived, the gendarmerie braced,” Mashaleh said.

‘The real recklessness is that of the king and none other than the king. There is no worse than this situation’

– Ali al-Brizat, Dhiban’s Hirak founder

The latest round of protests in Jordan started with a labour union strike on 30 May, which then grew into daily demonstrations across the country attended by thousands of people, resulted in the resignation of the prime minister, Hani al-Mulki, on the 4 June.

The next day the king appointed Omar al-Razzaz as his replacement, and the new premier quickly scrapped the income tax hike plans.

Jordan’s economy is struggling, badly.

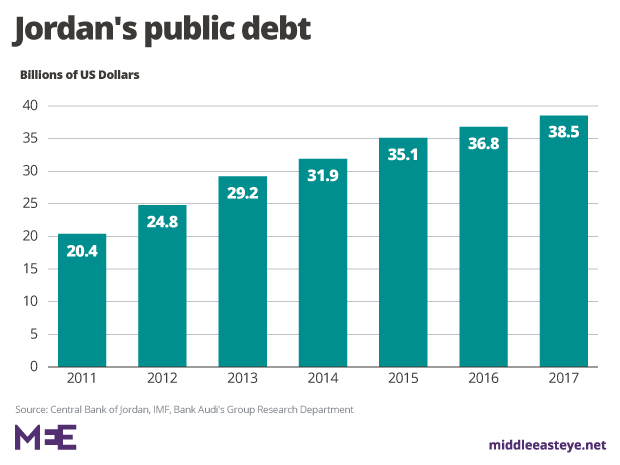

Up to the end of January, the kingdom’s total public debt stood at 27.4bn Jordanian dinars ($38.6bn) which is 95.6 percent of GDP, according to Jordan’s finance ministry.

In an attempt to find a solution to its problems, in 2016 Jordan secured a three-year credit line of $723m from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Since then, austerity measures agreed with the IMF have caused the price of basic goods such as bread, fuel, electricity and gas to rise steadily.

Mashaleh said that protests in Dhiban against rising prices started in January.

“We protested and gave speeches at Dhiban’s main square even before Amman’s protests kicked off in May,” Mashaleh said.

Dhiban’s square, where the protest tent stood for 58 days from April to June 2016 (MEE\Mustafa Abu Sneineh)

Dhiban’s square, where the protest tent stood for 58 days from April to June 2016 (MEE\Mustafa Abu Sneineh)During protests in February, Ali al-Brizat, a lawyer and founder of Dhiban’s Hirak, which is an alliance of political activists and protest groups, was arrested after making a speech criticising King Abdullah.

“These decisions [economic reforms cutting subsidies and raising prices] are beyond reckless. The real recklessness is that of the king and none other than the king. There is no worse than this situation,” Brizat, who was released from custody in March, was filmed saying during the protest.

Brizat then hinted that the protesters had support in unexpected places. “For how long? The intelligence department cannot shut us up. Their officers sit with us and ask us to speak out. Some are from the police, the intelligence and the army, they’re starving.”

When asked if protests would resume if Razzaz’s government failed to carve a path out of the economic crisis, Mashaleh said that in Jordan the “Hirak gets sick but never dies.”

Sabry Mashaleh: ‘We have a reputation among the police. Once they heard that Dhiban’s buses arrived, the gendarmerie braced’

Bread, freedom and social justice

Mashaleh is from Beni Hamaideh, the second-largest clan in Jordan after Beni Hasan, which is known as the tribe of one million strong.

Beni Hamaideh is Dhiban’s main clan and it extends to the towns of Madaba, Karak and At-Tafileh.

Dhiban’s district consists of 42 villages that host a population of 32,000. Almost half of them live in the central town of Dhiban.

According to Mashaleh, 60 percent of Dhiban’s population is unemployed.

He recalled a conversation between himself and an intelligence officer in 2016, when he and other unemployed Dhiban youths set up a protest tent at the main square to ask the government for jobs.

“He told me that they fear Dhiban’s youth the most. I asked him why, and he answered it was because Dhiban has the highest percentage of university-educated people in the kingdom and the highest percentage of oppressed. They know that there is something incorrect here,” Mashaleh said.

The protest tent was an offshoot of the events of 7 January 2011 when demonstrations started in Dhiban as part of the “Arab Spring” uprisings, then spreading to the whole of the kingdom.

“Our demands are bread, freedom and social justice. They are economic and social demands at the surface, but they are political at the core. Those demands are at the heart of any protest. They are straightforward demands, and everyone understands them,” Mashaleh said.

Mashaleh is currently unemployed, despite completing a BA in counselling and mental health at the University of Jordan in Amman. The unemployment rate in the country is 18.2 percent.

“I have worked, but I was sacked after pressure on my employer from security figures because of my political activity,” he said.

Dhiban’s protest tent stood for 58 days. Jordanian police forces destroyed it in June 2016, and clashes erupted in the town leaving several wounded by live bullets on both sides.

“The tent became a symbol for the protest in Jordan. We were eating, sleeping and making statements in it. We also did a live stream via Facebook and turned the tent into a TV studio where we did interviews. This annoyed the government,” Mashaleh said.

The tent created an atmosphere of solidarity and fraternity between people that lasts until today, Mashaleh said.

Mashaleh said he and like-minded, university-educated people cleaned the streets, painted the walls and guarded the neighbourhoods.

‘Our demands are bread, freedom and social justice. They are economic and social demands at the surface, but they are political at the core’

– Sabry Mashaleh, Dhiban’s protest tent spokesperson

As a spokesperson for the movement, he spoke with the police chief in Dhiban on 21 June 2016, eight days after the tent was destroyed and rebuilt it the next day.

“He accused us of wanting the fall of the regime and the royal family, but all that we asked for was jobs. We do not want the fall of anybody,” Mashaleh said.

“I told him if the country is corrupt, try and appoint us using these corrupt methods. But there were no jobs. We don’t want a job in a factory in Amman where the monthly salary is 230JD [$324]. You will not take much of it home,” Mashaleh said.

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Amman was declared in May as the most expensive city in the Arab world and 28th worldwide.

Meshaleh was detained for five days by the police over his involvement in the protest tent movement, and faced a list of 12 charges, including “undermining the political system” and “forming a gang of evil men”. He was cleared of these charges by the state security court.

An elected prime minister

Mashaleh has seen both sides of the political divide. In 2011, he was a pro-government demonstrator in Amman.

“I used to accuse the protesters of being troublemaker Palestinians and threw stones at them, and chanted in the name of the king,” he said.

But then he said he experienced a wake-up call.

Mashaleh said he realised that officials used a formula of blending blame for protests on Palestinians, the Muslim Brotherhood and foreign agents. The tactic leads nowhere, he added.

“I changed my beliefs after I realised that people suffer in Jordan from systemic corruption. I did not know that corruption existed because official media doesn’t inform you about it,” Mashaleh said.

“But after social media spread, the number of corruption cases that floated to the surface shocked me. There was no serious will to fight corruption, and people got poorer. This truth made me want to defend Jordan and stand in the face of injustice.”

In February, in Dhiban’s main square, Mashaleh made a speech saying no protests would address the king if there was an elected prime minister and government in Jordan.

“There is no elected government, so the king is responsible. All these government decisions are made with the king’s consent. We are calling to elect the government and the prime minister, then we will blame them for any decision because at the end of the day we elected them. We know that the king appoints them,” Mashalaeh said.

Pro-government protesters hold a poster of Jordan’s King Abdullah II during a demonstration after in Amman, 12 August 2011 (Reuters)

Pro-government protesters hold a poster of Jordan’s King Abdullah II during a demonstration after in Amman, 12 August 2011 (Reuters)In Brizat’s controversial speech in Dhiban’s square he described Jordanian ministers and parliamentarians as “puppets”, and said King Abdullah bears responsibility for what’s happening in the country.

Under Jordan’s current constitution the king is supreme commander, with all the ground, air and navy forces under his direct control. According to the constitution, King Abdullah has the authority to hire and fire prime ministers and dissolve parliament at will.

Many Jordanians spoken to by MEE expressed a wish to see some of that power transferred to a democratically elected government.

‘We will not accept you [King Abdullah] as a king, prime minister, defence minister, police chief and governor’

– Fares al-Fayez, opposition figure

Fares al-Fayez, an academic and a prominent opposition figure in the western town of Madaba, was arrested and then released in June after he was filmed criticising the king in a speech demanding a free election to vote for the Jordanian government.

“We want to change the political formula. We will not accept you [King Abdullah] as a king, prime minister, defence minister, police chief and governor. You are everything. You became a demigod, according to this constitution, and we are slaves,” Fayez said in his speech.

Fayez’s arrest caused shockwaves in Madaba, with members of his Beni Sakhr tribe threatening to block the main road between Amman and Madaba and disrupt flights from Jordan’s main airport unless he was released.

Mashaleh was at the news conference in Madaba when Fayez’s son threatened the measures.

“I agree with what Fayez said, but I disagree with the expression he used to describe Queen Rania. It was unnessacary,” Mashaleh said.

Fayez, who belongs to the Jordanian political right wing, described Queen Rania, the king’s wife, as a “Satan”.

“She came with her family as refugees from Kuwait, and now they own millions. She and her family looted the country,” Fayez said.

Queen Rania comes from a Palestinian family that was exiled by Kuwaiti authorities after the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) endorsed Iraq’s invasion of the Gulf country in 1990.

Hesham al-Haiseh, a prominent political activist from Dhiban, agreed with the need to change the system.

“We have tried the king’s decisions for the last 20 years and all of it was immature,” he told MEE. “By asking for an elected prime minister, we are asking the king to pass us the initiative to choose our decisions. He could stay as a king but allow us to choose our ways.”

Behind all of these demands and debate, lies a big question: are Jordanians ruling Jordan?

King Abdullah is from the Hashemite tribe that originated from the Hijaz region in modern-day Saudi Arabia. His family was pushed out by the al-Sauds in the 1920s after years of conflict in the Arabian Peninsula.

‘By asking for an elected prime minister, we are asking the king to pass us the initiative to choose our decisions’

– Hesham al-Haiseh, political activist

The Hashemites were welcomed by other tribes in Jordan, such as Beni Hamaideh, Beni Sakhr and Beni Hasan, after the First World War, and were instated as the country’s ruling family with British military and political support.

Alongside Hashemite rule, people native to Jordan have found political offices filled by other non-natives, such as Syrians, Palestinains and Circassians, people who have been received by the locals as they fled war or repression elsewhere.

Historically, most of Jordan’s prime ministers have been Syrian by origin.

Mashaleh and Haiseh both stressed that Jordanians welcomed the presence of the Hashemites, but Jordan’s people needed to have the major role in the running of the country. It was a point echoed by Fayez and Brizat in their speeches.

According to Mashaleh, the relationship between the royal court in Amman and Jordanian tribes has changed since 2011.

He said now the tribes have become more outspoken and critical of the king, as this folklore song blended with political messages performed in Dhiban in November 2012 shows:

Before 2011, Mashaleh and Haiseh said, members of the tribes were typically offered positions in state institutions with good security and benefits in exchange for loyalty. However, such benefits and positions have begun to disappear, they said.

Now, Mashaleh and Haiseh said, their generation is seeking to redefine the relationship with the royal court, to one that is based on rights and duties.

“We are citizens and we have rights,” Mashaleh said.

Though the royal court has kept the tribes on side for much of the kingdom’s history, Mashaleh is keen to note that they have had their rebellious moments in the past.

“The regime always send a message that we are loyal to it. But we have rebelled many times,” he said.

“[To see that] you could read Ayman al-Otoom’s novel The Story of the Soldiers, which tells the story of a revolt in the University of Yarmouk in 1986, which Jordanians were part of, alongside Palestinians,” Mashaleh added, referring to a historic political protest surpressed by the Jordanian security forces.

Hesham al-Haiseh: ‘By asking for an elected prime minister, we are asking the king to pass us the initiative to choose our decisions’

King Abdullah’s neo-shiekhs

Haiseh completed a BA in library management at the University of Jordan in Amman and now manages a school library. He also opened a coffee shop and a nusrery in Dhiban to help manage expenses. Three of his brothers are unemployed.

Haiseh lives and works in Amman but visits Dhiban on a weekly basis. He has been arrested seven times since 2011 because of his political activity. The longest he has been detained was five months.

In Haiseh’s opinion King Abdullah has used his reign to weaken the position of tribes in Jordanian political and social life – primarilly through appointing their leaders, or sheikhs, himself.

“He weakened the tribes in order to prevent them from becoming a danger to him,” Haiseh said.

The tribes consultancy, a body in the Hashemite royal court, decides who is accepted as a tribal chief.

“The true sheikh or tribal chief for us is the one that took his position from his father and grandfather. We will not accept he who is appointed as a chief from above with a letter from the royal court,” Haiseh said.

“This appointed shiekh is looking to use his position to benefit himself and his children. He will always obey [the king] and will not defend the tribe’s members before the royal court, the security forces and the intelligence services, as a true shiekh would do,” Haiseh added.

“A conflict between the appointed chief’s personal interest in keeping his position and the interests of his tribe was created during King Abdullah’s reign.”

Haiseh said that King Hussien, King Abdullah’s father, took care of the tribes, respected their traditions and did not interfere in how they choose their sheikhs.

“King Abdullah doesn’t believe in tribes. His education is British and claims he is enhancing the rule of law and abandoning the traditional laws and rules. But he deals with the tribes in a British way: divide and rule.”

King Abdullah was born in 1962. His mother, Princess Muna al-Hussien, is a British citizen, born as Antoinette Avril Gardiner. King Abdullah was schooled in Amman and continued his studies in England and the United States before he took the throne in 1999.

Meshaleh and Haiseh said until 2005 King Abdullah did not visit tribes in their hometowns, as the late King Hussien would do.

“He doesn’t know the country as his father did and the details of the people’s lives,” Haiseh said.

Rather than securing his position, Meshaleh and Haiseh said King Abdullah has only succeeded in pushing the tribes together by trying to weaken them.

Police secure the office of Jordan’s prime minister office during a protest in Amman on 2 June (Reuters)

Police secure the office of Jordan’s prime minister office during a protest in Amman on 2 June (Reuters)“Since 2011, Jordanian tribes and clans have had solidarity between them because they know they are targeted,” Haiseh said.

As an example, Haiseh pointed to July 2017, when a Jordanian soldier from the western city of Maan and member of the Huwaitat tribe was handed a life sentence for killing three American soldiers – prompting protests from a number of tribes.

“Tribes shut the three main roads that connect Jordan’s towns: the Dead Sea, the desert and the royal roads. This was to demand the soldier’s release,” Haiseh said.

Through mixing at workplaces, universities and across Jordan’s towns and citites, Meshaleh said the bonds between the tribes and their members were stronger than ever.

And in modern Jordan, the tribes’ political and social activism should come as no surprise, Meshaleh stressed, pointing out that they are no longer a nomadic people rooted in work such as shepherding.

“The regime always depicts us as Bedouins who don’t know anything; it always sends this message, especially to the West. But most of us abandoned this way of life,” Mashaleh said.

“You will find many intellectuals among us. They also depict us as aggressive and violent, although our protests were spontaneous and not organised by any political party,” he added. “It was peaceful.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.