Marina Ovsyannikova, the journalist who dramatically demonstrated against the Ukraine war live on Russian TV, wrote in German newspaper Die Welt on why she finally broke her silence, after spreading Putin’s lies for so long

By Marina Ovsyannikova, Die Velt Apr 18/22

Marina Ovsyannikova leaving a Moscow court last month after being fined the equivalent of $270 for her protest live on air. Credit: – – AFP

Marina Ovsyannikova, Die Welt

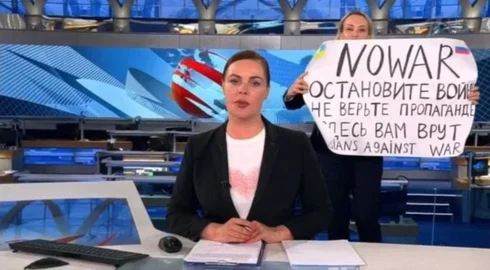

Until March 14, 2022, Marina Ovsyannikova was an editor with the Russian state TV broadcaster Channel One. Then she burst onto the set of the main evening news and held up a placard protesting the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

Ovsyannikova, the daughter of a Ukrainian father and Russian mother, was immediately arrested. A court fined her the equivalent of about $270, but she still faces charges of violating a law against “false news,” which makes it illegal to refer to the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a “war.” If convicted, she could be sentenced to up to 15 years in prison.

She writes here about her actions and explains why she remained part of the Russian propaganda machine for so many years…

After my protest on the evening news, my lawyers advised me to lie low and keep my mouth shut, so as not to put my life in any more danger. But I haven’t been doing that. I have been giving interviews to dozens of journalists from all over the world and posting anti-war messages on my social media channels.

I’ve been getting criticism since Day One. It doesn’t really matter what I do. Both sides attack me, Russians and Ukrainians. I’ve almost grown used to it. One minute Russians are calling me a British spy; the next, Ukrainians are calling me a Russian one. If I’d remained silent after my protest, people would have said it was odd that they weren’t hearing anything more from me. Now I’m speaking and writing about it, and they’re saying it’s odd that I can still do that. Others are saying my history disqualifies me from reporting independently in any case.

Russian Channel One editor Marina Ovsyannikova’s protest live on air during the evening news broadcast, March `14, 2022.Credit: HANDOUT – AFP

This last criticism mostly comes from independent journalists. And I understand that. Many of them have been risking their lives for years to fight against the system. I only decided to take a stand a month ago. What I can say, hand on heart, is that throughout all those years, I always read those brave journalists’ articles and admire their work. Their articles shaped my view of the world – and helped me finally find the courage to do what I did after all these years.

I spent many years working for the Russian state broadcaster, Channel One, where I was involved in creating aggressive Kremlin propaganda – propaganda that constantly sought to deflect attention from the truth, and to blur all moral standards. I was just a tiny cog in this system, but in my job I made sure that the system worked. I did not write or produce any propaganda pieces myself. But I helped others do so. And in the process, I earned enough money to travel extensively and make friends in many countries.

Among other things, my work involved picking out the right pictures from international news agencies – APTN, Reuters, Eurovision or AFP. I searched the internet for anything bad about the United States and other Western countries. When the United States banned the adoption of Russian children, we hunted for stories about bad American parents.

That was always a core part of the mission: to constantly tell people how bad life is in America, in the West as a whole and in Ukraine. That became the central theme: slinging mud at them all – only Russia is always soft, fluffy and whiter than white.

My job also involved scanning influential international newspapers for positive articles about President Vladimir Putin and Russia. Russia’s problems were never mentioned. There were clear instructions on the words we were allowed to use – the most famous current example being that we had to call the events in Ukraine a “special military operation” rather than a “war.”

What’s happening in Ukraine now is also bringing back memories of my teenage years. During the First Chechen War, I had to flee from Grozny with my family. We had to leave all our belongings behind and start a new life. Those were difficult years: we moved from one place to another, and we were poor.

A protester holding a placard depicting Marina Ovsyannikova’s protest against war on Russia’s most-watched evening news broadcast, during a rally in Paris in support of Ukraine, March 2022.Credit: THOMAS COEX – AFP

It was because of those years that I decided to study journalism. It might sound emotional, but I wanted to use this career to fight for more justice. The media landscape in Russia in the late 1990s was completely different from what it is today. When I started working in television, in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar, the media was relatively free and independent. And of course, back then we had hope that the future would be better.

The situation had certainly deteriorated by the time I moved to Channel One in 2004. But even then, no one who had chosen to work there could have imagined that Russia’s media would ever become the cynical and aggressive propaganda machine it is today.

My friends knew my liberal views, both then and now, and with every passing year became more astonished that I was still working for Channel One. I told them I didn’t want to give up my full-time job. I had been through a difficult divorce and had two children, a disabled mother, an unfinished house and a car loan. The working hours at Channel One were ideal: one week off, one week on – and even then, evenings only, seven or eight hours. I had time for my children. If I’d been working for any other media outlet, I’d have had to spend the whole day in an office, I’d have earned less money and I’d never have seen my children.The last straw

I tried to think of my work as if it were some kind of factory. I closed my eyes, worked my hours and then went home.

I watched Sky News and CNN, read The Guardian, The New York Times and The Washington Post. From the Russian media I read Kommersant, Nezavisimaya Gazeta and Meduza. I followed the independent Ukrainian media, the UNIAN news agency, Strana.ua, and the 1+1 and Inter TV channels. I saw very clearly the web of lies we were weaving.

When Russia denied any involvement in the shooting-down of passenger flight MH17 over Ukraine in July 2014, I was shocked but carried on working. When Alexei Navalny – the only person still telling the truth in Russia – was poisoned in August 2020, I was shocked but carried on working. But after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I just couldn’t do it anymore.

At first I wanted to take an anti-war placard to Manezhnaya Square in the center of Moscow, but my 17-year-old son locked me in our home, took my car keys away and told me to calm down. But I couldn’t sleep, eat or drink. And then the plan gradually grew: I wouldn’t hold up my placard in the city; I’d do it on air, during a live broadcast.

I sincerely regret my role in zombifying Russians with this propaganda. And I know, too, that by doing this I also helped shape people’s false impressions of Ukraine and the West. Today our propaganda goes so far as to try to portray all Ukrainians as nationalists and fascists. There are calls to exterminate all Ukrainians and throw all Russians who disagree with the war into jail or drive them out of the country. Pacifists in Russia are now called traitors.

It is crazy. Total madness. And I played a part in it, right up to the day of my protest. I did it even though I was born in Ukraine, in Odesa, and have two cousins in Ukraine. I have a very close relationship with one of them. She teaches art in Teofipol, western Ukraine. I spoke to her on the phone recently, and she’s on my side. She said she’d be willing to talk to the Ukrainian media and tell them I’m a good and decent person.

I cannot undo what I have done. I can only do everything I possibly can to help destroy this machine and end this war. If I can free just a few Russians from the clutches of Kremlin propaganda, if I can save the life of just one Ukrainian child, then the sacrifice will have been worth it.

Before the footage emerged of Russian war crimes against Ukrainian citizens in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, I said sanctions should only be imposed on Putin and his family, and that ordinary Russian citizens should not be made to suffer under them.

Since Bucha, I see it differently. I believe there have to be tough sanctions. That all Russians bear the collective guilt. Every one of us. Like the Germans after their crimes in World War II, we are going to have to spend decades begging for forgiveness for what we have done.

This article first appeared in Germany daily Die Welt last Friday.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.