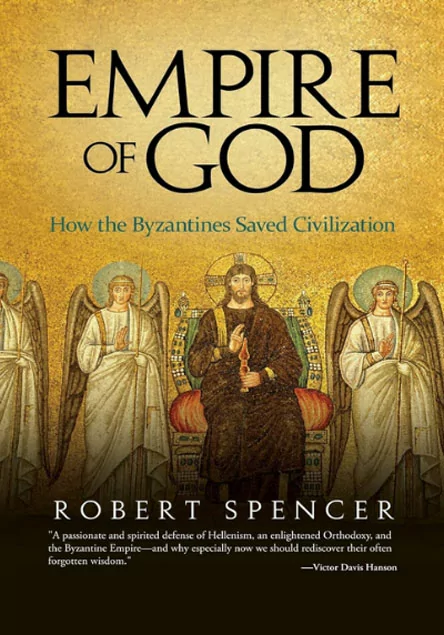

Robert Spencer’s new masterpiece unveils how the Byzantines saved civilization.

Founded as a kingdom in 753 B.C., Rome became a republic in 509 B.C. and an empire in 27 B.C By the fourth century A.D., the empire was so huge – extending from present-day Scotland to the Persian Gulf – that it was decided to divide it, for administrative purposes, in half, with one capital (and one emperor) at Rome and another at Constantinople. Most reasonably educated people in the Western world today are aware that our civilization began with Rome, and had its antecedents in Athens and Jerusalem. If we went to decent schools, we acquired at least some awareness of Rome; some of us read Virgil’s Aeneid, Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, and Robert Graves’s I, Claudius; those of us with a fondness for old movies have seen Roman epics like Spartacus and The Robe and Quo Vadis? We know that while the Greeks were big on philosophy and drama and art, the Romans were more practically inclined, constructing massive arenas and aqueducts, not to mention a number of roads that are still used to this day. No, we’re not experts on Rome, but it’s a part of our consciousness. Indeed, a series of postings on social media that were widely shared just a few weeks ago suggested that a not inconsiderable percentage of American men think about the Roman Empire several times a day.

Founded as a kingdom in 753 B.C., Rome became a republic in 509 B.C. and an empire in 27 B.C By the fourth century A.D., the empire was so huge – extending from present-day Scotland to the Persian Gulf – that it was decided to divide it, for administrative purposes, in half, with one capital (and one emperor) at Rome and another at Constantinople. Most reasonably educated people in the Western world today are aware that our civilization began with Rome, and had its antecedents in Athens and Jerusalem. If we went to decent schools, we acquired at least some awareness of Rome; some of us read Virgil’s Aeneid, Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, and Robert Graves’s I, Claudius; those of us with a fondness for old movies have seen Roman epics like Spartacus and The Robe and Quo Vadis? We know that while the Greeks were big on philosophy and drama and art, the Romans were more practically inclined, constructing massive arenas and aqueducts, not to mention a number of roads that are still used to this day. No, we’re not experts on Rome, but it’s a part of our consciousness. Indeed, a series of postings on social media that were widely shared just a few weeks ago suggested that a not inconsiderable percentage of American men think about the Roman Empire several times a day.

But what are they thinking about when they think about Rome? Almost invariably, they’re thinking about the Rome that had its capital in the city of that name – the Rome, that is, of Caesar, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. But if the empire centered at Rome – first, the united empire, and then the western empire – is very much alive in our consciousness, the eastern empire, which was ruled from Constantinople, isn’t. When we think about the timeline of history, that empire may well fall often between the cracks: we don’t know much about it; we don’t have much of a sense of it; we can’t picture it. If we think of the people of the western part of the empire as our forebears, we think of the eastern part as exotic – almost as alien, perhaps, as ancient India or China or Japan. And yet, as Robert Spencer writes in his magnificent, eye-opening new book, Empire of God: How the Byzantines Saved Civilization, the eastern part of the empire is also a central part of our heritage. Whereas the western part lasted barely a century after the east/west split, the eastern empire went on for more than a millennium. Today we know it as the Byzantine Empire, but in its day, during all those centuries after the city of Rome fell, what remained of the empire in the east was known simply as the Roman Empire, and Constantinople was, to all intents and purposes, the New Rome.

Constantinople, of course, was founded by and named for the Emperor Constantine, who ruled from A.D. 306 to 337, and whose personal conversion to Christianity was crucial to the establishment of that faith as the majority religion throughout the western and eastern parts of the empires. During his reign of a year and a half (361-363), Julian the Apostate, who worshiped Jupiter, Apollo, Venus, and all the other old deities, used strongarm tactics in an attempt to turn around the empire’s Christianization. Crisis came under Valens (364-378), who made the mistake of inviting Goths (who’d been conquered by the Huns) to settle in Thrace; soon enough, in the Romans’ most catastrophic defeat in centuries, the Goths turned on their hosts with “unspeakable savagery,” slaughtering them en masse in a years-long war that ended in Roman capitulation: ultimately, the Goths were permitted to remain in Thrace on their own terms, maintaining their distinctive culture rather than conforming (as had long been the expectation) to Roman norms. Spencer’s account of this nightmarish chapter brings to mind several current situations – the recent Hamas massacres and their aftermath, the ongoing Islamization of Europe, and the daily flow of illegal aliens across America’s southern border – and carries a chilling lesson for all those who look upon such matters with nonchalance. It was, by the way, Rome’s ill-advised immigration policies that were the principal cause of what has long been known as the “fall of the Roman Empire” in A.D. 476 – even though, as Spencer notes, the events of that year have long been misunderstood. “The unfortunate phrase ‘Fall of the Roman Empire’ has given a false importance to the affair of 476,” wrote historian John Bagnell Bury in a passage quoted by Spencer. “But no Empire fell in 476; there was no western empire to fall. There was only one Roman Empire.” And it lasted until 1453.

Most of us are familiar with at least the lineaments of early Christianity. After the gospel came the letters of Paul, a persecutor of Christianity whose conversion to the faith played a huge role in securing its future; and after Paul came Constantine, another convert whose acceptance of Christianity was also pivotal. In A.D. 325, he summoned the Council of Nicaea to resolve the theological dissension surrounding what would come to be known as the Arian heresy; from that council emerged the earliest version of the Nicene Creed, which is still a central part of almost all Christian denominations today. It’s not insignificant that the council took place in the eastern part of the empire, as did every one of the subsequent six councils that shaped Christian theology for all time – Constantinople (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople again (553, 680–681), and Nicaea again (787). In A.D. 380, the Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the empire’s official religion; and in an episode that illuminates the degree to which Christian clergy and Christian values actually carried weight in the empire, Theodosius, because he’d responded to the murder of a general by having many citizens put to death at random, was denied access to a church in Milan by the local bishop, Ambrose, who assailed him in the strongest terms: “How could you lift up in prayer hands steeped in the blood of so unjust a massacre?” Theodosius, instead of adding Ambrose to the death toll, accepted his rebuke and, returning to his palace, “shed floods of tears,” after which he strove to repent of his sins.

Among the more important later emperors was Justinian (527-565), whose reign Spencer describes as “Byzantium’s finest hour.” Justinian built the Hagia Sophia and introduced a legal code that was superior to the ones in effect at the time in Western Europe; under him, the empire survived a devastating plague and reached its greatest extent ever. Under Heraclius (610-641), the empire finally defeated the Persians after decades of combat but also lost the Levant to the bellicose adherents of the newly hatched Muslim faith. Leo III (717-741), deciding that the reason for the losses to Islam was the empire’s tolerance of religious images (which Islam rejected), tried to ban them; but the Second Council of Nicaea affirmed that venerating icons was consistent with Christian belief (although this ruling didn’t bring a total end to the struggle over iconoclasm). Nikephoros (802-811), perhaps under the influence of the Islamic doctrine that those who die in the act of jihad go straight to paradise, declared that soldiers killed in battle for the emperor were martyrs.

By the middle of the tenth century, the Byzantine Empire was the most powerful nation in the Western world, and Constantinople the most splendid city, an occasion of awe and wonderment to foreign visitors; classical education was undergoing a powerful revival, with “young noblemen boast[ing] of their libraries as a sign of their erudition.” Meanwhile Roman Catholicism and what was coming to be known as the Orthodox Christianity of the east were quickly diverging from one another. A great victory for the latter came when Prince Viadimir of Kyiv sought to pick out a state religion for his realm: his emissaries gave a thumbs-down to the worship services of the Bulgars and Germans, but were overwhelmed by the splendor and beauty of the ceremonies at the Hagia Sophia. Their report back to Vladimir played a crucial role in his eventual decision to enter Russia into the Orthodox camp. It was in 1054 that “[t]he thousand-year estrangement between the Eastern and Western churches” began; and it was around the same time that, because “Constantine IX [1042-55] first disbanded a large Roman army in the east, and then Constantine X [1059-67] preferred to rely on paying tribute and reaching out in friendship to the empire’s enemies rather than fighting them,” that the Byzantine Empire commenced its long decline.

A key factor in that decline was Islam, whose followers in Turkey defeated the empire in a series of wars in the late twelfth century, mostly during the reign of the incompetent Romanos IV (1068-71), shriveling it to half its size and devastating it economically. These losses were followed by the Crusades (1095-1291), in which warriors from all of Christian Europe passed through Constantinople on their way to liberate the Holy Land from the infidels. Alas, even after the Crusaders had driven the Muslims from the Levant, the latter continued to hold power in Asia Minor and to represent a threat to the empire. So, as it happened, did the Crusaders, who in 1204 sacked Constantinople, reducing the great metropolis, “the mistress of the world,” to ruins and destroying many of its priceless artistic treasures. For the contemporaneous historian Niketas Choniates, this barbaric act exposed the Crusaders as “frauds,” traitors to the holy cause that had allegedly motivated them to retake Jerusalem from the Muslims. After this indignity, the empire was crushed, but not yet dead: for two and half more centuries it stumbled along, and among the major developments was that Orthodox Christianity became increasingly oriented toward mysticism, even as Roman Catholicism headed in the opposite direction. It was on May 29, 1453, that Constantinople – and what was left of the empire – finally fell to the Muslim Turks, whose leader, Sultan Mehmed II, had ordered them to “slaughter all the survivors” and “plunder at will.” Entering the Hagia Sophia, in which “a large number of Christians” were “praying for the city’s deliverance,” the jihadis covered the floors with the blood of the supplicants and a cleric sent by Mehmed proclaimed from the pulpit the statement of the Muslim faith: “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammed is his prophet.” After nine centuries, the “cathedral was now a mosque.”

All in all, then, the tale of the Byzantine Empire is an immensely colorful one – a tale of some emperors who were virtuous and wise and strong and honest, and others who were evil and foolish and weak and corrupt; of endless palace intrigue, with one emperor deposing another and then being deposed himself, almost invariably in ways that involved unspeakable savagery; of messy transfers of power, also involving unspeakable savagery; of alliances and betrayals and invasions and wars and conquests and defeats, all of which, needless to say at this point, also involved unspeakable savagery. Through it all, right up until its ignominious fall, Constantinople remained the envy of every other city in Christendom – rich in learning and culture, respectful of the ancient Roman legal tradition, and devoted to the perpetuation of classical Greek schooling. Among the areas in which the Byzantine Empire influenced the contemporary Western world – especially the U.S. – is law: Justinian’s legal code, notes Spencer, was “highly valued among America’s Founding Fathers,” notably Adams and Madison. Spencer further points out that if the Second Council of Nicaea had forbidden iconography, Western art would never have undergone the flowering that made possible everything from Michelangelo to Dali. And Spencer writes about all of it with elegance and insight, bringing to life one Byzantine emperor after another – plus many other prominent players – and making this reader, at least, exceedingly grateful to have become more fully acquainted with the rich history of the mysterious empire in the east.

This brief synopsis of the book is almost as enthralling as the book itself must be. There are tons of lessons and insights to be gleaned from the history of the Byzantines, but they are certainly lost to our corrupt and ignorant politicians. One immediate lesson to be learned is the danger to civilization of Islam. It is a savage religion, so those who oppose it must be even more savage, or at least more relentless. When, security is restored to the world, only then we will be able to dwell in peace. But, to everything there is a time.

The Western Roman Empire officially ended in 476 AD, when its barbarian ruler took on the title “King of Italy”; but Rome and Ravenna (the residence of the Pope) continued, on and off, to be ruled by Constantinople. This ended in 750-51, when the Lombards pushed the pope out of Ravenna, and he re-established himself in Rome. He then got help from the King of the Franks, forming the basis of the Holy Roman Empire.

As a result of these events, the Eastern Emperor (and later on, the Tsars), dominated the church; whereas the Western (Holy Roman) Emperor was largely dominated by the Pope.

Correction: Gibbons wrote the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. My bad.

Don’t forget Ben Hur and Gibbons’ The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, among the early classics of our day, not to mention the importance of the Latin language in Medicine and Law. It’s impossible to separate Western culture from its Hebrew, Greek and Roman roots.