It is our own individual responsibility that must play a part in saving the order of things.

By Emina Melonic, AM GREATNESS

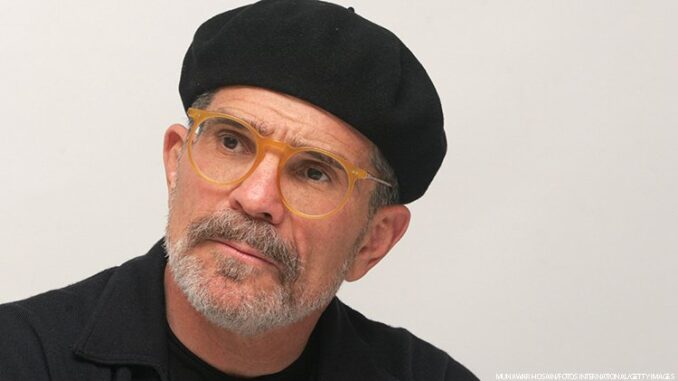

I first encountered the work of David Mamet in my undergraduate English seminar on modern American drama. We read many of his works, but after all these years, what sticks out is Mamet’s 1987 screenplay “House of Games,” which he also directed. I was in my very early 20s, only a few years after my arrival to America from Bosnia. Although I spoke English well, the nuances in Mamet’s use of the language were something very new to me.

Yet, I was deeply attracted to it. The pace, the quickness, and sheer authenticity of speech for each character is filled with Mamet’s own authentic and uncompromising vision. In “House of Games” in particular, no word or line is wasted. As a viewer and a reader, you have to pay attention, but that isn’t difficult because every movement (be it visual or linguistic) pulls you into the labyrinthine world of the con men and con women.

After discovering Mamet’s work, I continued to seek more, but I didn’t really pay attention to his politics. They didn’t matter to me, anyway; I was only interested in the art. In 2011, however, Mamet published The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, in which he eviscerated leftism’s doctrines. Based partially on his 2008 essay published in the Village Voice, “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead’ Liberal,” The Secret Knowledge explores what exactly is wrong with leftism and why leftism is intent on destroying America.

This was not an ideological journey for Mamet (not that the words “ideology” and “journey” go together, anyway), but a deeply personal one. He questioned how and why he supported leftist views. As he writes in The Village Voice essay, “. . . although I still held these [leftist] beliefs, I no longer applied them in my life. How do I know? My wife informed me. We were riding along and listening to NPR. I felt my facial muscles tightening, and the words beginning to form in my mind: Shut the fuck up. ‘?’ she prompted. And her terse, elegant summation, as always, awakened me to a deeper truth: I had been listening to NPR and reading various organs of national opinion for years, wonder and rage contending for pride of place. Further: I found I had been—rather charmingly, I thought—referring to myself for years as ‘a brain-dead liberal,’ and to NPR as ‘National Palestinian Radio.’”

Leftist film and theater critics (are there really any other kind?) have had a hard time accepting Mamet’s political views, yet they’re caught in their own “Catch-22,” an existential condition that plagues every leftist. They can’t help but admire Mamet’s work and see the significance of it, yet they issue disclaimers upon disclaimers about how it’s “unfortunate” and “sad” that Mamet has lost his political way. It’s a hallmark of a leftist pseudo-intellectual to “gift” the conservative with a heap of pity and condescension in an effort to induce an apology and contrition from the said conservative.

Today, American culture is even more dismantled. With Barack Obama, America started to put all of these academic theories into practice, and now, political correctness has reached another level of absurdity. In his typical style (a blend of cultural analysis, memoir, and drama), Mamet explores the current social and political predicament in Recessional: the Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch. He touches upon many subjects: media, Judaism, wokeness, Donald Trump, literature, and inevitably, COVID. The political game has changed and Mamet is fully aware of this. The book is not so much an argument against leftism (since categories of “Left” and “Right” have changed or in some cases, been erased) as it is a way to bring down conformity, collectivism, and mediocrity. These three components are what drive Mamet’s thoughts, implicitly and explicitly.

The problem of culture is not simply political, claims Mamet, but also religious. He’s not saying that everyone needs to find God, hitting us over our heads with a two-by-four, but the Jewish tradition from which he bases his beliefs clearly guides his thoughts and analysis. He’s rightfully aware that what is causing much of the chaos in our world is man’s refusal to see perennial aspects of human nature. We are fallen beings, and in many ways (as Qohelet/Ecclesiastes tells us) “What has been will be again/what has been done will be done again;/there is nothing new under the sun.” Some people have no humility and seek false idols so they can worship them and feel better about their own mediocrity and inadequacies.

Art has been one of the casualties of wokeness. Unless it serves leftist ideology, it will not be accepted as a legitimate form of art. As if we need the leftist komissars’ imprimatur in order to create! Mamet continuously makes a distinction between ideology and art, and touches upon the mind of an artist. “Outreach, education, diversity, and so on are tools of the indoctrination,” he writes, “But art is the connection between inspiration and the soul of the observer. This insistence on art as indoctrination is obscenity, denying and indicting the possibility of human connection to truths superior to human understanding, that is, to the divine.”

There is something mysterious about the process of inspiration and writing that even most writers are unaware of, especially during the act itself. An ideologue, on the other hand, totalizes everything: art, politics, other people, and himself. But that’s not the only thing an ideologue does. He is one of the most conformist people because he masquerades as an intellectual. He needs someone else to tell him what to do (see, for example, a blind acceptance of Anthony Fauci) because he cannot think on his own.

Mamet makes a rather fascinating claim that the leader of the Left is none other than Donald Trump. Does this sound nuts? Upon closer inspection, it makes perfect sense. Mamet writes that “For the last six years the Left has had a leader, his supposed omnipotence equal to that of Hitler, Mao, Castro, and Stalin, one to whom all attention must be paid.” This is Trump, because the Left “couldn’t find anyone on the bench to send in, so they chose the rival team’s most powerful player and instructed the faithful that it was opposite day.”

The American political and cultural scene usually functions on this level: the Left acts (always in the state of change, disruption, and revolution) and the Right reacts (always ready to mount a defense of the order of things). But Trump did something quite different and brilliant. He disregarded the Left’s ramblings and forced them to play by his rules. This is why there is such a thing as the “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” and despite the fact that Trump is not in office, “TDS” still continues in some form or the other.

Being an actual thinker, Mamet levels criticism at anyone who lacks the courage also to be one and stand up against collectivism. He writes, “Observe that every conservative who employs the preface ‘This may not be politically correct but’ is not only acknowledging but aiding the forces of thought control. These forces do not need to be acknowledged and whether or not they are opposed, they must not be strengthened.” This approach, which clearly comes from Mamet’s authentic interiority, is one of the things that makes Recessional a great book.

I hesitate to use the word “inspirational” to describe Mamet’s book because that word tends toward schmaltz and naiveté. He’s not warm and fuzzy, which is one of the positives of his work. He’s straightforward, honest, sometimes cranky but funny, and more than anything, he doesn’t give a damn about appeasing anyone. It’s refreshing to read a work that is not repressed.

Mamet is not presenting solutions to the cultural and political problems because these are ultimately matters of the soul. But, thanks to his openness and knowledge of American, Jewish, and European culture, a reader will be inspired to think further on these ideas. (Read the book with a pen and paper close by because your reading list will exponentially grow). This is a work of neither idealism nor pessimism. Much like the film director John Ford, Mamet doesn’t sugarcoat America’s issues. But he does elevate the possibility of individual independence and human flourishing by delving into the specifics of American uniqueness.

Perhaps it is both art and religion that will save the world. Speaking of Moses’ great hesitancy to be a leader, Mamet singles out the significance of the burning bush that awakens Moses from his slumber. “What is the burning bush, which will not cease burning?” writes Mamet. “It is his [Moses’] mind. He was living a lie in the comfort of the palace, and he is now living a lie in the illusion of ‘uninvolvement.’ The bush will not stop burning until he confronts the truth.” It is our own individual responsibility that must play a part in saving the order of things. This is America’s big confrontation, and it will take courage. But much like Moses, we are not alone, and we must vanquish fear.

There is no place for a rebel soul in today’s America.