I steel-man Bret Weinstein

Francisco Gil-White | The Management of Reality | Sep 06, 2024

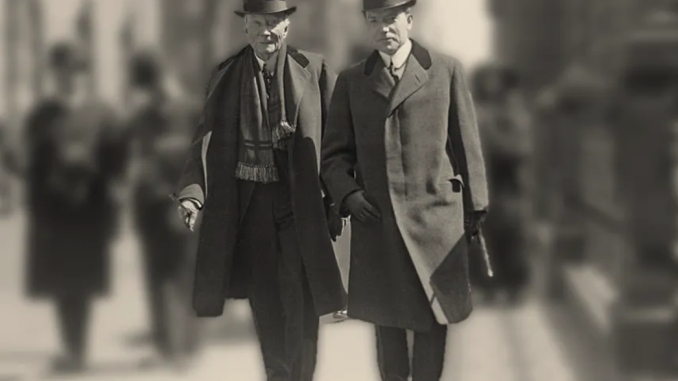

John D. Rockefeller Sr. and Jr.

If you missed Part 1 of this series, you may read it here:Are the Western bosses PSYCHOPATHS? Part 1: Bret Weinstein: “I wouldn’t put it past them”

In a recent podcast, Bret Weinstein has proposed that, as a scientific exercise, we should build models of our political universe on the most extreme version of conspiracy theory. We should presume, in other words, that the bosses are psychopaths.

What would that mean? Well, in Wikipedia’s mainstream definition of the concept:

“Psychopathy … is characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism, often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of … normalcy.”

Let’s not beat around the bush: “impaired empathy and remorse” means that a psychopath is untroubled by another’s suffering; extreme psychopaths are gratified by that suffering, and they delight in the opportunity to inflict it themselves. Think of the ancient Romans, who built stadiums to watch innocent humans get eaten by lions—that’s the picture. But such monsters are not always easy to spot because psychopaths can dissimulate to avoid detection; when adaptively imperative, they deploy a “superficial charm” to convince members of ethical communities that they are ‘normal’ (see Part 1).

So Weinstein is saying this: What if the bosses are only pretending to be moral and democratic persons? What if, like the ancient Romans, they are seriously disturbed individuals—evil, frankly—who delight in making us suffer? How much can a model of our democratic political world explain if built on that assumption?

Let’s find out, he says.

This may sound to you like an extreme proposal, but I think we should take it seriously. First, because our modern democracies are hardly designed to impede the upward climb of charming psychopaths to positions of great power. And, second, because whoever goes a-prospecting in our recent democratic history for potential cases of psychopathy among the bosses will come back with an embarrassment of riches.

Or so I claim; the demonstration follows.

I will proceed chronologically. The present piece is focused on some important diagnostic events of the period 1900-1938 in the United States, with a significant glance, in closing, at the Western system more broadly. Future pieces will cover later periods. But for any period, please keep this in mind: I am giving you a partial list.

(NOTE: As you peruse my examples in this and future pieces—which collectively double as a kind of annotated guide to the investigations published so far on MOR—you may begin to wonder what exactly we are up to. In which case we recommend our ‘About MOR’ page, where we aim to provide meaningful and satisfying answers.)

Robber barons vs. muckrakers

To answer this question, we must consider the work of those ferocious researchers of yesteryear, pioneers of investigative journalism, who decided to speak Truth to Power and rake some robber-baron muck: the muckrakers.

Not unlike us free bloggers and podcasters who fight the cartel or ‘trust’ now controlling our reality-making institutions, the muckrakers of the early twentieth century, and the magazine editors who championed them, fought the corrupting influence of the robber barons, who were rapidly seizing clandestine control of the entire market for daily news (as the muckrakers angrily documented).

Beyond that fight for press freedom, the muckrakers rose in outrage against dishonest political capitalism, or crony capitalism. They documented and denounced that the robber barons were engaged in political rent-seeking: corrupting the State to protect their monopoly power to fleece consumers. And their holiest indignation was reserved for the violent abuses that the robber-baron monopolists visited on industrial workers.

What was the muckraker’s solution? Like everybody else at that time, left or right, the muckrakers believed that crony capitalism leading to oppressive, rent-seeking monopolies was the only capitalism possible.1 They were attracted, in consequence, to socialism, and wanted, in the short term, to grow the regulatory power of the State.

For reasons I do not fully understand, the muckrakers couldn’t add two plus two on this question. They couldn’t see that, because socialism requires an all-encompassing monopoly of monopolies, it will necessarily produce—as history amply proves—the most atrocious rent-seeking and oppression (that’s what monopolies do). Nor could they grasp that growing and strengthening a State already corrupted by the cronies could only make crony capitalism worse.

The big monopolists, by contrast, could add two plus two. They cleverly allowed their muckraking enemies to push for greater State regulation over their industries, then worked hard to control the resulting legislation. Historian Gabriel Kolko has carefully documented the implementation of that strategy, and has recognized—quite despite his own socialist bent—that a bigger State only made the problem worse. Indeed, he argues explicitly against the traditional and official narrative that even today we are still learning in school, which claims that a ‘progressive’ State supposedly enacted these reforms to punish the excesses of the bosses and protect the public. No, says Kolko: the ‘antitrust’ regulations, crafted by the bosses themselves, did little or nothing to improve life for consumers and workers; in truth, they were designed to erect formidable entry barriers for would-be competitors—added State protection for the robber-baron monopolies!

And yet the monopolies were never complete because maverick, free-market entrepreneurs kept finding ingenious and unanticipated strategies to enter the market and compete, despite the robber baron’s regulatory advantages. This was a rather dramatic demonstration of the liberating power of markets, and was so recognized by Kolko—again, quite despite his own preference for socialism.2

What Kolko’s work—if not his ideology—strongly implies is that the solution to crony capitalism lies in ever freer markets. Free markets for buying and selling, certainly, but also in other domains. In politics, we call such free markets democracy; in information distribution, the free press; in knowledge creation, science; and in worship, freedom of religion. If we don’t want crony capitalists wrecking everything, then let’s make things easier for their competitors, I say.

But though I disagree strongly with the muckrakers on the solution, I nevertheless feel, as one who rakes some muck, profound respect for them as detectives and ethnographers. And I salute, moreover, the moral outrage that made them brave.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.