Within two days of historic White House event, PM has had to backtrack from vow to immediately apply Israeli law to settlements. What went wrong, why, and how much does it matter?

30 January 2020, 9:58 pm

President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during an event in the East Room of the White House in Washington, Tuesday, Jan. 28, 2020, to announce the Trump administration’s much-anticipated plan to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

Many supporters of the settlement movement rushed to cheer Tuesday’s unveiling of US President Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” as the most pro-Israel peace proposal in history.

There were some misgivings about the plan’s vision for a future Palestinian state, even if it was conditioned on a list of demands many of which the Palestinians will never accept.

But concerns over Trump’s endorsement of a “realistic two-state solution” were drowned out by jubilation over the green light the proposal gave to Israel to immediately annex the Jordan Valley and all settlements in the West Bank.

But merely 24 hours after the plan was unrolled at the White House, celebration turned into frustration.

“I’m very disappointed,” right-wing pundit Shimon Riklin, usually a die-hard supporter of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, told The Times of Israel on Wednesday, a day after he literally danced with joy on the streets of Washington. “I expect him to keep his promise, and to implement what he said he would — before the elections.”

Riklin’s heart was aching, he tweeted a short while later. “I really hoped that there would be an application of sovereignty,” he told his 100,000 Twitter followers.

The dispiritedness of Riklin and many others on the Israeli right appeared to be the product of either a tactical error by Netanyahu, or extremely poor coordination between the Israeli government and the White House’s peace team. Or both.

From immediately, to a month or more: What happened?

It all began on Tuesday around noon, in the East Room of the White House, where Netanyahu and Trump presented the administration’s peace plan at a festive ceremony attended by Republican Congressmen, Jewish communal leaders, prominent evangelical figures, and three ambassadors from the Arab Gulf.

“Israel will apply its laws to the Jordan Valley, to all the Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria, and to other areas that your plan designates as part of Israel and which the United States has agreed to recognize as part of Israel,” Netanyahu declared in an address immediately after Trump had unveiled the plan.

But Netanyahu did not say when he would do it.

The president, in his remarks, had mentioned a plan to form a “joint committee” in which the US and Israel would convert the plan’s conceptual map “into a more detailed and calibrated rendering so that recognition can be immediately achieved.”

This appeared to mean that the US would immediately recognize Israel’s forthcoming annexation of the relevant territories.

Even if that annexation took place next week? The president did not say.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks with US President Donald Trump during an event with in the East Room of the White House in Washington on January 28, 2020. (AP/Susan Walsh)

Mere moments after the ceremony at the White House, Netanyahu promised, during a briefing to reporters, to bring his annexation plan to a vote at next week’s cabinet meeting. Those meetings usually take place on Sundays, the reporters pointed out. Netanyahu nodded in agreement, indicating that Israel would formally start the process of extending sovereignty over large parts of the West Bank within days.

Citing the likely need to overcome some bureaucratic hurdles, Tourism Minister Yariv Levin, who was sitting next to Netanyahu, interjected that the cabinet vote might be delayed until Tuesday.

Journalists working for right-wing outlets were overtly ecstatic. Israel was finally extending sovereignty to its biblical heartland, they enthused. It was almost too good to be true.

US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman, the plan’s co-author, confirmed in a press briefing Tuesday afternoon that Netanyahu could implement the annexation anytime he wished to. “Israel does not have to wait at all,” Friedman replied definitively, when asked if there was a “waiting period” before the government could apply sovereignty over the settlements.

US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman (L) speaks with US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin before US President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announce Trump’s Middle East peace plan in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC on January 28, 2020. (Mandel Ngan/AFP)

“The waiting period would be the time it takes for them to obtain internal approvals and to obviously create the documentation, the calibration, the mapping, that would enable us to evaluate it, makes sure it’s consistent with the conceptual map,” he added. “If they wish to apply Israeli law to those areas allocated to Israel, we will recognize it.”

The first serious question mark over the immediacy of annexation was raised by Jared Kushner, Trump’s senior adviser and the head of the team that wrote the peace plan. In an interview on CNN later on Tuesday, Kushner said he did not believe Israel would annex anything in the coming days. This stood at odds with Netanyahu’s declared intention to have the matter voted on in Jerusalem within days, seemingly indicating flawed communication between the two, at best.

The next morning, Friedman held another press briefing and was asked to clarify the matter of annexation timing. He acknowledged the need to establish a joint US-Israeli committee, but still appeared to say the Israeli government could proceed as and when it pleased, although his comments were not entirely definitive.

This committee would work “with all due deliberation to get to the right spot, but it is a process that does require some effort, some understanding as some calibration,” Friedman said. The Israeli government “will do what it’s going to do, but then the committee will form,” he added.

The American side, he went on, will soon designate its members of the panel, and once the Israelis do the same and present their proposal, “we’ll consider it as part of the agreement, and then we’ll make a decision.”

“I’m not going to go beyond that right now, and I’m not going to speculate how long that will take,” he said. “We are cognizant that this is something that we’ll get to work on right away, and we’ll try to get to the answer quickly.”

In the course of Wednesday afternoon, anonymous Israeli officials appeared to start backtracking from the vow of an imminent annexation, saying that more in-depth work was required, including the preparation of maps via satellite images. Other leaks blamed “security reasons” for the delay.

Jared Kushner gives a television interview outside the White House on January 29, 2020, in Washington. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images/AFP)

Finally putting an (apparent) end to the confusion, Kushner, in an interview on Wednesday — while Netanyahu was airborne en route to Moscow — unequivocally declared that the administration is opposed to an immediate annexation.

“The hope is that they’ll wait until after the election,” Kushner told GZERO Media, stressing that the White House would not back Jerusalem if it were to rush into annexing anything before the March 2 poll. Asked directly whether the Trump administration would support an immediate decision by Israel to annex the Jordan Valley and West Bank settlements, Kushner answered: “No” and elaborated that “we would need an Israeli government in place” before moving forward.

Some Israeli officials were subsequently quoted as saying that Jerusalem might ignore Kushner’s statement, but it was generally believed that Netanyahu would not risk antagonizing the White House in this way at this time.

What does the proposal itself say about annexation?

The Jordan Valley “will be under Israeli sovereignty,” the Trump document determines. It further stipulates that the Jewish state “will incorporate the vast majority of Israeli settlements into contiguous Israeli territory.”

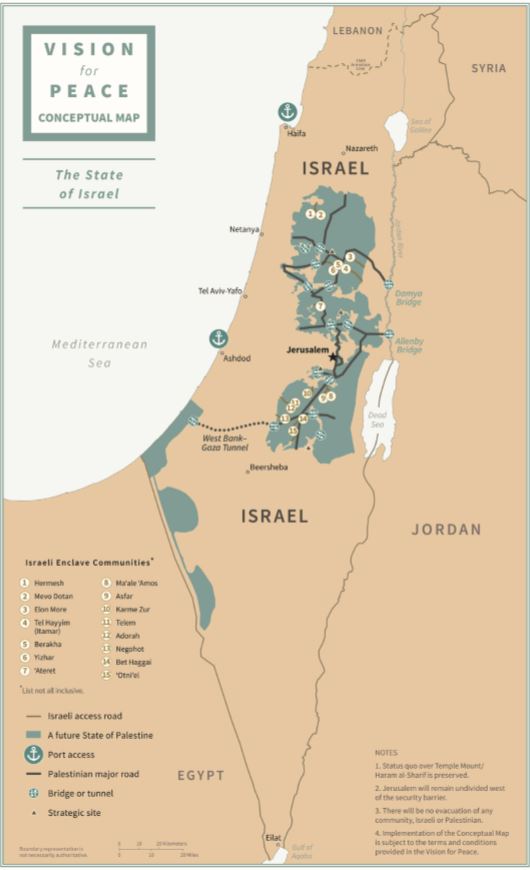

Vision for Peace Conceptual Map published by the Trump Administration on January 28, 2020

Section 22 calls on Israelis and Palestinians to start negotiating, adding that both sides “should conduct themselves in a manner that comports with this Vision, and in a way that prepares their respective peoples for peace.”

The document does not specify when Israel will be allowed to start the annexation process.

But the wrangling over the timing misses the bigger picture, a senior Israeli official in Netanyahu’s delegation to Washington and Moscow complained to reporters.

“There is no argument over substance. There is only a minor technical issue,” he said.

Initially, Israel wanted to perform the annexation in one, two or possibly three stages, the senior official said, speaking on condition of anonymity. Applying Israeli law to the Jordan Valley and established communities in the West Bank is relatively simple, he explained.

A view of the Israeli West Bank settlement of Ariel, January 28, 2020. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

But other areas, especially the territories surrounding the settlements and other uninhabited parts, is more complicated, requiring the drawing of maps with the help of geologists on the ground using satellite images and the like.

Therefore Israel was hoping to deal with the more technically straightforward phase immediately, and leave the more complex part for a later stage, the official explained.

The Americans, however, prefer everything to be done in one fell swoop, this official claimed, because they don’t want to have to formally recognize Israeli annexations several times.

So was it all just a misunderstanding?

The senior official did not want to speak of a misunderstanding, deflecting any criticism of either the Israelis or the Americans. But it certainly seems that the saga could have been avoided if Jerusalem and Washington had been better coordinated ahead of the plan’s rollout.

After all, the proposal was three years in the making, and both sides knew that annexation would be a major part of it. Kushner and Friedman were no doubt aware that a month before the elections, Netanyahu would attempt to market the green light he received for annexation to try to bolster support. If they didn’t want Netanyahu rushing to announce that annexation was imminent, they could have told him so.

Another possible explanation for the confusion is the existence of separate camps, or at least divergent stances, within Trump’s peace team. Friedman, a longtime enthusiastic supporter of the settlement movement, may have encouraged Netanyahu to press ahead with annexation, while Kushner wanted the prime minister to tread more lightly.

Jerusalem-based Friedman is probably convinced that the peace plan will have no chance of proceeding to an agreed Israeli-Palestinian accord, and may therefore be mainly interested in guaranteeing Israel gets what it was promised.

Washington-based Kushner, however, is deeply engaged with Arab leaders from across the region. His goal may well be working to give his father-in-law’s peace plan the best chances of success. An immediate, unilateral Israeli annexation of large chunks of the West Bank would clearly dampen the Arab world’s support for the deal.

US President Donald Trump, left, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu take part in an announcement of Trump’s Middle East peace plan in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC on January 28, 2020. (Mandel Ngan/AFP)

To be sure, there is no crisis between the Netanyahu government and the Trump administration. The two staunchly support each other — and regard the plan as significant, beneficial to each other, and popular with their constituencies — and that is not about to change.

But the sensitive issue of annexation often does cause friction between Washington and Jerusalem, including in the Trump era.

In February 2018, for instance, Netanyahu said at a Knesset meeting of his Likud faction that he had been discussing annexing the West Bank with the Americans “for a while now.” His comment made headlines in Israel, leading a White House spokesperson to issue a blunt denial: “Reports that the United States discussed with Israel an annexation plan for the West Bank are false. The United States and Israel have never discussed such a proposal, and the president’s focus remains squarely on his Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative.”

This week, no one denied that annexation was openly discussed. It’s a cornerstone of an administration plan both parties regard as historic. But the confusing back and forth about the timing revealed unease about the issue. Under the previous administration, this may have been called daylight.

I don’t think the plan itself mentions the word “annexation.” It seems to say that none of the plans’ provision’ would come into effect until an agreement was signed between the two parties. It is presented as a proposal for a peace treaty between the parties, not as a unilateral plan for Israel. I don’t know where the “immediate annexation” idea came from. Possibly from Netanyahu’s informal discussions with various people in the rump administration. It is not in the Plan itself.

One wonders why the details and bugs weren’t worked out and agreed upon before the “Deal” was rolled out.