T. Belman. Its gratifying to read an article from a conservative think tank in Israel which makes the same arguments that Markovsky, I and Pelonoi and I have been making. Also it is notable that one of the authors was formerly with the Council of Foreign Relations.

Photo credit: Shutterstock.

Public support in the West for the war in Ukraine rests upon three frequently repeated assumptions:

Russia’s invasion was unexpected and unprovoked.

Ukraine is a unified and democratic nation.

Ukraine can win the war and regain its lost territory.

None of these is true.

The United States strongly opposed the Soviet Union placing missiles in Cuba. Washington would never accept a Chinese naval base in Nova Scotia. So is it surprising that Russia opposes turning Sevastopol in Crimea (where its Black Sea fleet remained based after the USSR collapsed) into a NATO facility, which is what would happen if Ukraine became a NATO ally? For three generations, American ambassadors to Moscow delivered clear and consistent warnings to Washington against expanding NATO into Russia’s traditional sphere of influence.

George Kennan was America’s ambassador in Moscow during the Truman administration. In 1948 he wrote that “no Russian government would accept Ukrainian independence,” and that any attempt to create an independent Ukrainian state would be “artificial and destructive.” Alarmed by NATO expansion in 1998, Kennan told New York Times columnist Tom Friedman that, “I think the Russians will gradually react quite adversely…..I think it is a tragic mistake.”

Jack Matlock was America’s ambassador to Moscow during the Reagan administration. Appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the Clinton administration he stated, “I consider the recommendation to take new members into NATO at this time misguided. It may well go down in history as the most profound strategic blunder made since the end of the Cold War.”

William Burns, currently the CIA director, served as ambassador to Moscow during the George W. Bush administration. He advised Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all red lines for the Russian elite (not just Russian President Vladimir Putin). In more than two-and-a-half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.”

Instead of heeding these explicit warnings from senior diplomats, Western politicians consistently rejected Russia’s calls for a neutral Ukraine. The alliance repeatedly reconfirmed Ukraine’s right to join NATO. As the alliance expanded eastward, it provided ever more arms transfers, defense planning and intelligence sharing to Kiev. Russia felt threatened. It is disingenuous to claim that its reaction came as a surprise.

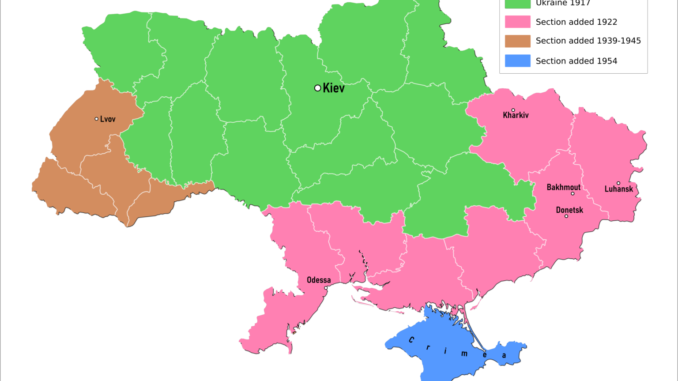

Modern Ukraine is a recent creation with a complex history. Over the past 400 years it has been governed in part and at various times by Russians, Poles, Lithuanians, Austrians, Germans, Cossacks, Turks, and Swedes. It became an independent nation in 1991. Its Russian-speaking southern and eastern regions were separated from Russia and annexed to Ukraine by Vladimir Lenin in 1922. The western region around Lemburg was Austrian until 1918 when it became Polish and the city’s name was changed to Lvov. Joseph Stalin then annexed this region to the Soviet Union in 1945 and changed the city’s name yet again to Lviv. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev added the ethnically Russian Crimea to Ukraine by administrative fiat in 1954.

Not surprisingly, the country remains sharply divided along political, linguistic, and religious lines. Politically, Ukraine is divided between pro-European and pro-Russian factions, with those seeking closer ties to Russia found mostly among Orthodox Christians living in the east and Crimea. This division is not new. Fifteen years ago, the American ambassador in Moscow wrote to Washington that the issue of Ukraine’s NATO membership “could split the country in two, leading to violence or even, some claim, civil war…”. He was correct. In 2008, when NATO’s Secretary General declared that Ukraine would eventually become an alliance member, thousands of Russophile demonstrators took to the streets in protest, particularly in Russian speaking cities like Odessa and Kharkov.

Unlike Canada, which found ways to meld Anglophone Protestants and Francophone Catholics into one nation, Ukraine failed to embrace pluralism. Ukrainian nationalist governments in Kiev rejected a federal model with autonomy for Russian-speaking regions. They rejected calls to adopt two official languages throughout the nation and went so far as to ban the use of Russian in administrative and commercial matters, even in predominantly Russian-speaking regions.

While the country is divided linguistically between Russian and Ukrainian speakers, religiously it is divided primarily between Catholic and Orthodox Christians. The majority of Ukrainians are Orthodox Christians who have for centuries looked to Moscow for religious leadership. In 2019, well before the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian government sought to break this ancient connection by establishing a new denomination under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Patriarch in Turkey. Then in December 2022, Ukraine adopted legislation completely banning any religious organizations affiliated with Russia. In effect, Russian Orthodox Christians are now free to worship only in government-approved churches that look to religious leaders in Kiev and Istanbul rather than Moscow.

Ukraine’s unity remains tissue-thin. Many ethnic Russians and Russian speakers living within the country’s modern borders do not identify with Ukrainian nationalism and never have. Now viewed as enemies, their political parties, media outlets and churches have been closed. Whether this is a genuine matter of national security or simply an effort to eliminate opposition to the current Ukrainian nationalist government is a matter of opinion, but these divisions existed long before the Russian invasion which has only deepened them.

It might have been easier to unify an independent Ukraine if its government had been less corrupt or more democratic. In 2016, then Vice President Joe Biden said that corruption was “eating Ukraine like a cancer.” Transparency International currently lists Ukraine as tied for the second most corrupt nation in Europe, according to an index of perceived corruption; it is one where bribery and embezzlement in the defense, energy, education and justice systems have become endemic.

Far from being a flourishing democracy, Ukraine is an impoverished, corrupt, one-party state with extensive censorship, where opposition newspapers and political parties have been shut down. Freedom House’s most recent assessment listed Ukraine as only “partly free,” and notes that “attacks against journalists, civil society activists, and members of minority groups are frequent, while police response is often inadequate.” Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the UN High Commission on Human Rights have all detailed significant human rights problems in Ukraine.

While a generation of Ukrainian youth is dying in the Donbas mud, the sad truth is that Ukraine has as much chance of defeating Russia as Mexico would of defeating the United States. How can a nation with a current population of 35 million and a 2021 GDP of just $200 billion hope to defeat a nation of 145 million with a GDP of $1.8 trillion? While Russia remains self-sufficient in food and energy, much of Ukraine’s infrastructure lies in ruins. While Russia possesses a sizable defense industry, Ukraine remains heavily dependent on NATO for armaments. Russia has put its growing economy on a war footing, called up the reserves and assembled hundreds of thousands of troops. Ukraine, on the other hand, has a shrinking economy, exhausted armories and a growing manpower shortage.

Prolonging this conflict with more Western arms deliveries will not change its outcome. Only NATO boots on the ground can avert Ukrainian defeat and that entails unacceptable risks. During the Cold War, Western leaders worked diligently to avoid direct military conflict with the Soviet Union. They recognized that, unlike Moscow, NATO has very little strategic interest in who controls Donetsk. They certainly were not willing to risk a nuclear war over Kiev. Ukraine is not a member of NATO, and the alliance has no moral or legal obligation to defend it. Putin has made it clear that any foreign troops entering Ukraine will be treated as enemy combatants.

Sending NATO troops into the Ukraine would thus turn our proxy war with Russia into a real war with a nation whose nuclear arsenal exceeds our own. And for those with outdated views of what that could mean, let them reflect on the fact that the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima had the equivalent power of fifteen thousand tons of TNT while the Russians now possess thermonuclear hydrogen bombs with the power of fifty million tons of TNT.

The price of peace in Ukraine is affordable. It can be based firmly on the positive principles of neutrality, economic development and self determination. Russia went to war to prevent NATO from stationing troops 300 miles from Moscow. A settlement will require guarantees of Ukrainian neutrality similar to those agreed to by Austria in 1956. Frankly, it has never been obvious why an explicitly defensive alliance like NATO needs to expand its membership to the borders of Russia.

On the other hand, Russia can have no legitimate security objections to Ukraine joining the European Union – just as neutral Austria did almost twenty years ago. EU membership for Ukraine should be a clearly stated condition of any agreement to end the war, as should specific commitments from major Western nations to help fund Ukraine’s reconstruction. An incentive for Russia to agree to a ceasefire would be for the West to begin dismantling its economic sanctions regime against the Russian economy and leadership.

Self determination is a long cherished American principle. Let us have a ceasefire and a UN-supervised referendum to determine if the people of Crimea and Donbas really do want to join the Russian Federation. The people of Quebec and Scotland were given an opportunity to vote on their political future. Why not the people of Ukraine?

The war in Ukraine, like so many wars before it, grew from misunderstanding and hubris. It is time to end this tragedy before Ukraine is covered with yet more tears and ashes. It is time to replace hyperbolic rhetoric with common sense.

David H. Rundell is a former chief of mission at the American Embassy in Saudi Arabia and the author of Vision or Mirage, Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads. Ambassador Michael Gfoeller is the former political advisor to the US Central Command. He served for fifteen years in diplomatic assignments in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

Ambassador Michael Gfoeller is a former political advisor to the US Centa member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.