The Dutch did not save the Jews during the Holocaust, they betrayed them during the war and afterwards. Except for a very few, their actions toward Jews went from active hostility to indifference.

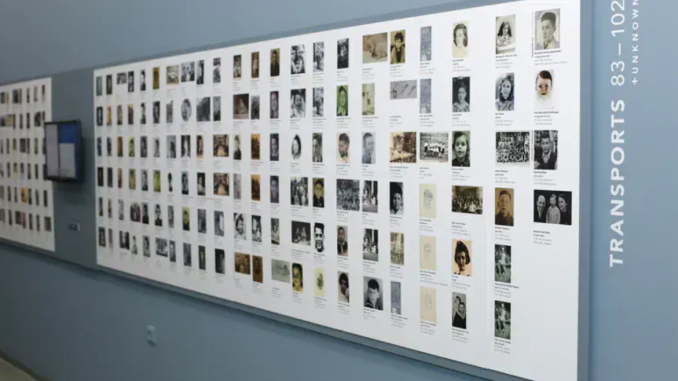

In memory of Dutch Jewish children Beit Lochamei Hagetaor

In memory of Dutch Jewish children Beit Lochamei Hagetaor

We watched in horror as Israelis were viciously attacked in a pogrom in Amsterdam after attending the Maccabi TLV-Ajax soccer match. One is reminded (or should be informed if one does not know) of the Dutch response to the Jews when the Germans invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940.

During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Holland did not join the resistance in huge numbers asserts Elma Verhey, a Dutch investigative journalist for Vrij Nederland. Very few Dutch offered to help their Jewish neighbors or colleagues as they were being deported.

Facilitated in the Destruction of Dutch Jews

As Verhey explained, most Dutch citizens were not only indifferent to the plight of the Jews, but many segments of the society assisted in facilitating the destruction of their fellow Dutch citizens. Of all the Nazi-occupied countries in Western Europe, the Netherlands had the highest proportion of Jewish victims. The country also had one of the largest Nazi parties in Europe. Between 22,000 and 25,000 Dutch served in Waffen-SS.

In 1941, there were 140,000 Jews in the Netherlands, yet only between 10,000 and 20,000 managed to secure a safe haven, and half of them, like the Anne Frank’s family, were betrayed. A little more than 16,000 survived in hiding according to historian David Cesarani.

The famous Dutch tolerance which for centuries had allowed Jews to be accepted with relatively few difficulties, ”proved to have another side” Verhey observed,

Most of the Jews in the Netherlands resided in Amsterdam, a geographical fact that exacerbated their problem, Verhey said. Most of their contacts were other Jews. Even if they had the funds to pay a non-Jew to protect them, where could they find one?

German historian Peter Longerich points out that the process of arresting and deporting Dutch Jews by the Security Police proceeded more smoothly than in any other country under German occupation. For the most part, the Jews were not seized in raids or “actions,” but in their homes by Dutch policemen who forcibly evicted them. The Germans knew precisely where the Jews lived, because Dutch civil servants provided the Germans with their addresses.

Transported to Transit Camps at Westerbork and Vught

Dutch train conductors transported Jews to train stations, while the Dutch Railway supplied the German administration with detailed invoices for adding extra trains to the Westerbork transit camp in the Northeastern part of the country. Verhey asserts.

By the end of 1942, 38,000 people had been deported Longerich said. After a one month “Christmas break,” the deportations resumed in January 1943. In general, each week a train transported the Jews from Westerbork to Auschwitz. During the middle of January a second transit camp was opened in Vught in the southern part of the country. In March, Dutch Jews were sent to the in Sobibor extermination camp where practically all were murdered as soon as they arrived. Out of the 34, 313 Jews deported to Sobibor, only 19 survived. Only 19!

The Netherlands: Post-War

Without the cooperation of the Dutch civil service and its bureaucracy, Verhey concluded, “the extermination of more than one hundred thousand Jews some eighty percent of all Jews who lived in Holland before the, war—could not have been possible.”

Despite the devastating losses Dutch Jews sustained, and the decimation of their communal life, Cesarani found that the Dutch government in exile, did not recognize the importance of arranging a special provision for the Jews. Incongruously, the Dutch who gave their lives to safeguard their Jewish neighbors were the most resolute in eliminating all religious and racial categories in forming policy in the post war.

There was little understanding and sympathy for the Jews , Cesarani said, especially from those in the north who underwent severe hardships throughout the final winter. Returning camp survivors were regularly stopped and interrogated along with Dutchmen who had freely gone to work in Germany. At times they were investigated together with members of the Dutch Nazi party (the Nationaal Socialistische Beweging the NSB).

When the government established a procedure to compensate those who had suffered under the German occupation, Cesarani said the Jews were strongly advised “not to strain the patience of those to whom they ought to feel gratitude.” Anti-Jewish sentiment “in the immediate post-war period reached such a pitch that citizens who had hidden Jews preferred not to advertise their bravery.”

Jewish War Orphans

The future of the 2,041 Jewish war orphans who had been hidden with Chrisitan families or institutions became an issue of contention after the war. Historian Joel Fishman, a pioneer in the study of the fate of these Jewish war orphans, said their “situation was unique in that, throughout the war , the [Dutch} Resistance kept some form of records of the children whom they hid. ”Even before the end of hostilities, they had devised plans for their care, with the full support of the Dutch Government.”

Unlike in other European countries, few Jewish children were placed in monasteries, and only a small fraction were baptized. Approximately 3,500 survived the war. After 1,4 17 children were reunited with one or both surviving parents, it left 2,041 orphans, 1,300 of whom were under 15 years of age Fishman said.

The Netherlands government viewed the Jewish war orphans as a national concern, and officially acknowledged the claim by the Resistance groups to be consulted in deciding the children’s future. Members of the Resistance asserted the criteria should be the physical, psychological and nutritional wellbeing of the children They were first and foremost considered to be Dutch and there must be concern about the trauma the children and foster parents might experience. As Fishman pointed out, this action was in direct contravention of Dutch family law that an orphan be raised in the faith of his deceased parents.

The Jewish community rejected the position of the Resistance, since they were Jewish children, and the Dutch had the responsibility to return them to their Jewish community. Fishman said it ultimately appears that about 1,500 were transferred from their foster homes. Five hundred children seems to have stayed in non-Jewish environs. Some returned to Judaism of their own volition.

Fishman concluded that the “bitter memory of this controversy persists as well as the awareness of many Dutch Jews that their minority rights were violated and their fellow Dutchmen treated them ignobly and ungenerously in view of the terrible suffering during the Holocaust.“

Dr. Alex Grobman is the senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society and a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East. He has an MA and PhD in contemporary Jewish history from The Hebrew university of Jerusalem. He lives in Jerusalem.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.