Peloni: Highly recommended reading. Wurmser provides an important analysis of the realigning shift of power relations which are taking place in the wake of Israel having devastated Iran and its proxy forces.

China, Cairo move toward Erdogan as Iran recedes in newly threatening, fast-changing Mideast reality

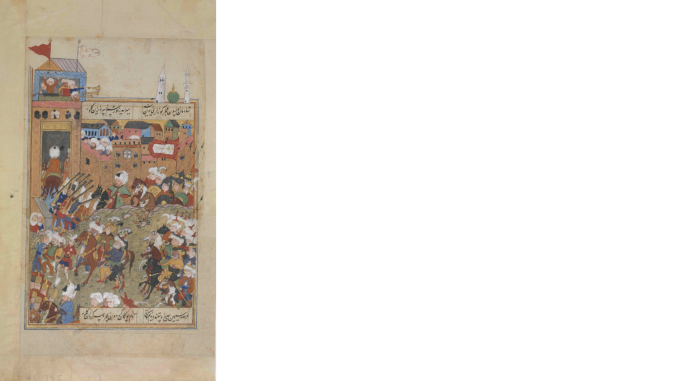

“Ottoman Army Entering a City,” Folio from a Divan of Mahmud `Abd al-Baqi, last quarter 16th century. Attributed to Turkey. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Bequest of George D. Pratt, 1935. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Ottoman Army Entering a City,” Folio from a Divan of Mahmud `Abd al-Baqi, last quarter 16th century. Attributed to Turkey. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Bequest of George D. Pratt, 1935. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The desolation wrought on Hezbollah by Israel, and the humiliation inflicted on Iran, has not only left the Iranian axis exposed to Israeli power and further withering. It has altered the strategic tectonics of the Middle East. The story is not just Iran anymore. The region is showing the first signs of tremendous geopolitical change. And the plates are beginning to move.

First things first. The removal of the religious-totalitarian tyranny of the Iranian regime remains the greatest strategic imperative in the region for the United States and its allies, foremost among whom stands Israel. The Iranian regime, in its last days, is lurching toward a nuclear breakout to save itself. Such a breakout would not only leave one of the most destructive weapons in one of the most dangerous regimes in the world —as President Bush had warned against in 2002 — but in the hands of one of the most desperate ones. This is a prescription for catastrophe. Because of that, and because one should never turn one’s back on a cobra, even a wounded one, it is a sine qua non that Iran and its castrati allies in Lebanon be defeated.

However, as Iran’s regime descends into the graveyard of history, it is important not to neglect the emergence of other, new threats. Indeed, not only are those threats surfacing and becoming visible, but the United States and its allies need already now, urgently in fact, to start assessing and navigating the new reality taking shape.

These new threats are slowly reaching not only a visible, but acute phase. They only increase the urgency of dispensing with the Iranian threat expeditiously. Neither the United States nor our allies in the region have any longer the luxury of a slow containment and delaying strategy in Iran. Instead, a rapid move toward decisive victory in the twilight struggle with the Ayatollahs is required.

The retreat of the Syrian Assad regime from Aleppo in the face of Turkish-backed, partly Islamist rebels made from remnants of ISIS is an early skirmish in this new strategic reality. Aleppo is falling to the Hayat Tahrir ash-Sham, or HTS — a descendant of the Nusra force led by Abu Muhammed al-Julani, himself a graduate of the al-Qaeda system and cobbled together of ISIS elements. Behind this force is the power of nearby Turkey. Ankara used the U.S. withdrawal from northern Iraq a few years ago to release Islamists captured by the U.S. and the Kurds. It sent some to Libya to fight the pro-Egyptian Libyan National Army under General Khalifa Belqasim Haftar based in Tobruk. It reorganized the rest in Islamist militias oriented toward Ankara. The rise of a Muslim-Brotherhood dominated Turkey, rehabilitating and tapping ISIS residue to ride Iran’s decline/demise to Ankara’s strategic advantage, will plague American and Israeli interests going forward.

Added to this is the power vacuum created by the destruction of Hamas. The defeat of that terrorist group has been, for good reason, a critical goal for Israel and the United States, but it is one that also involves consequences that must be navigated and hopefully countered. The world of Hamas is a schizophrenic one. It has two heads, aligned with different internal fractions — one more anchored to the world of Sunni, Muslim Brotherhood politics led by Turkey and the other to the Iranian axis. In 2012 Israel killed Ahmad al-Jabri, a scion of the powerful al-Jabari clan lording over Hebron but who had transplanted westward to become the leader of the Murabitun forces (part of the Izz ad-Din al-Qasem Brigades) within Hamas in Gaza. He had transported those forces to train under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Mashhad, Iran, in the years before and became the driving force of Hamas by the time Israel felt it had to deal with him. Despite his demise, the structures he led anchored to Iran continued to grow and assume ever more dominance over the Hamas structure, in part because of the release, in the 2011 Gilad Shalit hostage-release deal, of several key figures, including Yahya Sinwar. But Iran did not cleanly control all of Hamas. Turkey maintained a powerful presence in the organization and had some senior Hamas leaders likely more loyal to Turkey than to Iran. In many ways, Hamas reflected the schizophrenia of its patron, Qatar, which served a critical ally to both Iran and Turkey in the last two decades.

In the past two decades, however, Iran proved more ascendent strategically in the region than Turkey. In fits and starts, Ankara had tried quietly to compete with Iran in the last two decades, but more often than not it was left only to nibble at the scraps left by Iran along the edges, whether in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon (after the August 2021 port explosion, for example) or among the two structures of geopolitical discourse, the “Lingua Franca” embodiments of regional competition — the Palestinians and the Islamists. Hamas, therefore, as well as the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (an organization whose fealty was far more homogeneously held toward Iran), became increasingly far more defined by Tehran than by Ankara. Iran had become the region’s new Nasser, and its minions accordingly flourished as did its factions in Palestinian and Islamist politics.

However, suddenly the ground shifted. Israel has, since summer 2024, starting with Operation Grim Beeper and the demolition of Hezbollah, triggered an earthquake in the normally slow pace of regional strategic change. If Israel presses onward with priority, as it should, to devastate and destabilize the Iranian regime, and if the Iranian axis meets its demise, then Hamas—indeed all Palestinian and Islamist politics—drifts to a Turkish direction and they slowly emerge as Ankara’s strategic assets. This reorientation does not represent an increase in the Palestinian threat to Israel, but it would be the triumph of hope over experience to think it would reduce it. Indeed, it is likely no more than an exchange of a rabid donkey for a crazed mule.

The emergence of the Sunni, Muslim Brotherhood bloc, which includes Turkey’s slow drift to a dangerous position, as a strategic problem accelerated under President Obama. Turkish leader Tayyip Erdogan always was an Islamist politician. Yet until Obama, Erdogan’s attempts to recreate some sort of neo-Ottoman Caliphate and reignite its imperialist ambitions had been disconcerting but largely symbolic and rhetorical. It was, however, latently concerning, because the reference point on which Erdogan focused—resurrecting the terminated Ottoman Caliphate in 1921—also serves as common ground with the most dangerous Sunni Islamist movements, such as al-Qaeda, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad group (which was renamed Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn), and Fatah al Islam, ISIS and the assortment of al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliate groups across the Maghreb in Africa. There was always the danger of convergence of the Turkish and the most radical Islamist worlds into one strategic threat.

In 2011, President Obama made at least two critical mistakes.

First, instead of supporting indigenous Syrian opposition such as the Free Syrian Army, which sought closer ties to the West, President Obama subcontracted to Turkey and Qatar the task of defining and supporting the opposition to President Assad of Syria as the Syrian regime descended into civil war. The threat of ISIS has thus remained ever since, and with Iran receding, Turkey surfs the crest of the ISIS-remnant wave.

Second, the U.S. tried to sustain Syria as a unified fiction of a state, fearing its partition. The same mistake was replicated in Libya, which had strategic consequences for Egypt. As a result, Egypt is also now drifting in a dangerous direction. The insistence on retaining a unified state meant that to survive in conditions of communal, sectarian, tribal, ethnic civil war, each faction within that state had to fight to the death for control over the other rather than disengage into partitioned pieces. Control meant survival while being controlled meant being slaughtered. This fueled the Syrian refugee crisis.

Given the calamity that befell Syria and the chaos that lies underneath, as well as these hovering strategic forces positioning already to scavenge the Syrian nation’s cadaver, it is important for both Israel and the United States, along with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, to contemplate as soon as possible many scenarios that hitherto were outlandish in the western end of the fertile crescent. It is too early to identify and digest fully, let alone definitively plan for the reality that will emerge. Now is the time, though, for some initial thoughts that might undergird a longer-term strategic planning process.

First, to be clear; Iran remains the central threat. And nothing can be done until it is defeated. But the urgency of ensuring and achieving its defeat is increasing rapidly.

With Iran’s defeat, Syria will begin unraveling. Russians will try to protect essential interests there — Assad’s Alawite regime and the Christian communities, especially the Greek Orthodox. It is not only the last remnant outside Cuba of the Soviet global bloc, but also a more civilizational sense of commitment to the remains of the world of Byzantium. As several current Russian political commentators, intellectuals and religious leaders have posited, Russia considers itself to some extent the “Third Rome” — Rome and Constantinople being the first two. The remnant Christian communities — especially the Greek Orthodox since the Maronites are Catholic and orient more to France — are envisioned as Moscow’s charge.

A Russo-Turkish confrontation might threaten Israel and America but it could also present opportunities. Russia may consider turning to Israel as a key offset to Turkish power once Iran is removed from the picture.

Moreover, China is likely to realign with Turkey and drop Iran when it realizes the Ayatollah regime is falling. China has hedged for the past few years, having signed a strategic agreement with Iran in 2021, but it has just as aggressively sought to tighten its relations with Turkey. Part of what drives Beijing and Ankara together is the strategic competition between China and India. China has ties to Pakistan through the Hindu Kush range and sees India as one of its premier enemies. Turkey as well has close strategic relations with Pakistan, uses that relationship to compete with India in Afghanistan, and has attempted in the last half decade to destabilize India both through using Pakistani help to rile up unrest in the Jammu and Kashmir, but also among India’s 200 million Muslims. As Iran falters, we see China shifting more toward Turkey.

And we see Egypt also recalibrating. This was in part because of Libya, but also the unrelenting pressure of the Biden administration on human rights and Washington’s tolerance of Qatar and the Muslim brotherhood regionally against the Saudis and Egypt. At first, Egypt retrenched into close alliance with the Saudis and positioned itself as Erdogan’s nemesis — even to the extent of supporting the Syrian regime in its efforts to withstand pressure from Turkey and its Islamist allies. But the pressure of Washington (paused during the first Trump presidency) mounted, and Egypt increasingly moved from confrontation to cooption of the internal Islamist threat. This process began under the Obama era — which led to a strategic shift away from peace, away from Israel, and away from viewing Hamas as a profound strategic and domestic threat, and instead toward slow accommodation of Hamas and Turkey.

The post-October 7 closure of the Red Sea and by extension Suez – and the unwillingness of the United States to reverse that, which Cairo viewed as an inconceivable abdication of American power — shook Cairo. It made it more attractive to align with the Muslim Brotherhood, Erdogan and China. The evidence of this shift has been exposed in recent months. As the war progressed, and especially after Israel captured Rafah and the “Philadelphi” border region between Egypt and the Gaza Strip, the level of Egyptian tolerance that was exposed of a far-more expansive Hamas smuggling network through the Sinai surprised even the Israelis. That smuggling could not have been done without the knowledge of all levels of Egypt’s security structures, and indeed various examinations of the network indicate that Egyptian officials profited off this trade in the hundreds of millions of dollars, or even billions. The tight cooperation between Israel and Egypt to check Hamas and curb Erdogan’s intrusion into Gazan and Egyptian affairs still evident in 2014 had somehow shifted toward Egyptian indulgence of Hamas and Iran and Turkey’s support for it. Another sign that this shift is accelerating recently was the sudden release of 800 Muslim Brotherhood operatives by Egypt last week. Such a blanket release indicates a material strategic shift — the Muslim Brotherhood is the vanguard of Erdogan’s threat to the Egyptian regime — not a minor gesture. For the moment, Egypt is not forced to choose whether to side with the emerging Turkish-Sunni Muslim Brotherhood-Chinese bloc or the Russo-Iran bloc. While clearly abandoning the West, it has yet to leap wholeheartedly into the Turkish camp. The power of Russia and the residues of history still have their grip to some extent on Cairo.

In other words, we already see a mass realignment underway to digest the fall of Iran and the rise of an imperial Turkey. If Syria approaches a final failure and collapse, what pieces might emerge?

A proper Lebanese state anchored to its Maronite foundation is one desirable outcome.

Beyond that are some less conventional prospects. The U.S. and Israel should start planning for an Alawite state further up the Mediterranean coast. Syria is unlikely to remain a single country. Russia may find that it will be able only to hold a rump Alawite state and Christian communities (Greek Orthodox — not Maronite) and retreat to protect an enclave state. It will also rapidly come to see Iran as useless in this regard and split from Iran on Syria — or what’s left of it.

How might the United States and Israel relate to the desperate Russian-oriented enclave entity?

Russia had envisioned a new foreign policy approach, launched a year ago at the Valdai Conference in Sochi and unveiled in Putin’s speech there on October 5, 2023. He proposed cobbling together the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) nations into one geopolitical strategic bloc to challenge the West. But that vision and the underlying unity upon which the Valdai vision is anchored now is being torn to shreds. Russia likely will reach out to India and a post-Ayatollah Iran, but less as a hostile challenge to Israel and the West and more as a desperate move to prepare itself and preserve its dwindling assets in the emerging Russo-Turkish confrontation.

It is strategically wise to consider now how one handles the disintegration of Syria.

It is likely that Russia will be forced to retreat into an effort to protect the Alawite and Christian (especially Greek Orthodox) communities, which it will likely only be able to do by creating a rump Syria state in traditional Alawite and Christian areas. Given that Russia relies on access to the area via Syria’s ports in Latakia, Tartus, and Banias (especially Tartus) along the Mediterranean coast, it will most likely anchor that rump entity along the eastern Mediterranean with strategic partners in Lebanon, and then a rump Alawite state to the north of that in Tartus and the surrounding mountains.

Putin has proven thus far that he is able to adjust or evolve his strategic vision, but only slowly. He suffers some rigidity. It is possible that Russia will remain so focused on imperial European ambitions that it falters and falls — along with its Iranian ally — in its survival in the region.

Yet it’s also conceivable that Russia may reach out to cooperate with the U.S. and Israel to save its position. If so, the U.S. and Israel will be faced with a decision about how much to cooperate with Russia against Turkey and China or how much to try instead to anchor the post-Syria structures to U.S. and Israeli power independent of Russia. It’s complicated, too, by the fact that Turkey is a member of NATO and home, simultaneously, to some of the remaining Hamas leadership and to the U.S. Air Force’s Incerlik Air Base.

It’s time to start noodling these questions — even the outlandish ones. Trump didn’t spend much time during the presidential campaign talking about the threat of Turkey. He did, though, often warn that we are closer than ever to World War III.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.