Francisco Gil-White | The Management of Reality | Oct 20, 2024

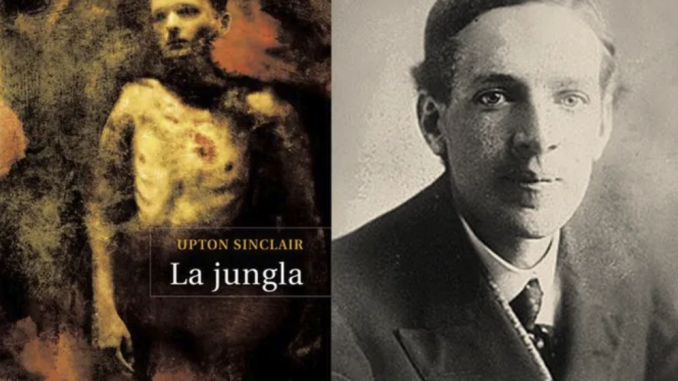

Photo on left by Unknown Author licensed under CC BY-NC-ND . Photo on right by Unknown Author licensed under CC BY-SA.

Photo on left by Unknown Author licensed under CC BY-NC-ND . Photo on right by Unknown Author licensed under CC BY-SA.

- Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle depicts the suffering of industrial workers in the Chicago meatpacking district in the early 20th century.

- They were treated like slaves—or worse.

- But why? Were the US bosses psychopathic?

The system of political capitalism, as some theorists have named it, or crony capitalism, as others call it, saw a full flowering in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.1

Political capitalism was a well-integrated system created by the biggest industrial bosses to reduce ‘democratic’ government into a branch—a functional tool—of their business interests. This system famously included widespread graft, plus police and military repression to control the workers. It also included, though this is not as well known, manipulation and clandestine consolidation of the media.

But the political capitalists had a thorn on their side: the muckrakers.

The muckrakers, as pioneers of investigative journalism, got busy shocking the middle classes in the United States with their exposés of political corruption at all levels. And they made known the abject suffering of industrial workers. As a consequence of their work, a widespread movement for reform developed that threatened to give direction to what the ‘robber barons’—as the biggest bosses came to be called—had long considered a potentially revolutionary situation.

The robber barons and their allies lost a lot of sleep over that. One scholar of this period remarks that “the concept of labor problems—particularly in the singular as ‘the Labor Problem’—gained currency in the early 1880s and was soon regarded by many observers as the most serious domestic social issue in the country.” A prominent economist of that time, John R. Commons, put it this way in 1919: “ ‘If there is one issue that seems likely to overthrow our civilization, it is this issue of capital and labor.’ ”2

As soon as you grok that central fear you begin to make sense of the major political activities of the robber barons, especially their investments in the management of reality. Their entire approach, I have claimed, is consistent with psychopathy.

As a contribution to that argument, I will here strive to familiarize you with the suffering imposed by US industrial bosses on workers during the so-called Progressive Era.

I will begin with a few words about the historical and pedagogical censorship, because this stuff has mostly been expunged from the standard historical education that US citizens receive. And then I will give you a taste for what has been censored.

The historical and pedagogical censorship

In Lies My Teacher Told Me, sociologist and historian James Loewen reports on his investigation of bias in the history textbooks that are employed in US schools and remarks on how the working conditions of these immigrant laborers are usually erased from the official narratives. The ‘nation of immigrants’ theme is of course stressed, as it is central to the identity created for modern US citizens. “But when textbooks tell the immigrant story,” writes Loewen,

“they emphasize Joseph Pulitzer, Andrew Carnegie, and their ilk—immigrants who made supergood. Several textbooks apply the phrases rags to riches or land of opportunity to the immigrant experience. Such legendary successes were achieved, to be sure, but they were the exceptions, not the rule.”5

The rule, for a lot of people, was rags to rags. Or rags to death. Yet, textbooks strive to “present immigrant history as another heartening confirmation of America as the land of unparalleled opportunity.”6

A very different picture emerges from the muckraking journalists who documented the lives and tribulations of these immigrant laborers. Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), a leading muckraker, gave the middle-class public a window into the suffering of the immigrant poor in his well-researched novel The Jungle, published in 1906, which describes life in the Chicago stockyards.

The Jungle quickly “sold out in nearly every bookstore across the country” and transfixed the United States, becoming the center of a heated policy battle.7 I will briefly summarize its contents below. As you read, please keep in mind that the experiences of coal miners, steelworkers, and so on, which Sinclair also chronicled, were different only in the specific details of each industry, but quite similar in terms of the indignities and raw suffering.

The successful immigrant—myth and reality

Yet those who can, return. Some return because they are suffering unemployment in the US. But it’s harder to return when you don’t have a job that pays you; most returnees go back because they’ve made some money and are terribly homesick, as they don’t much like it in the United States. Depending on their country of origin, between 25% to 60% of them do so.9 But these returnees do not include, of course, those whom the US has lost, broken, or killed. Hence, there is a selection bias on the information that people back in Europe are getting, which makes lots of people back there think that opportunities in the US are better than they actually are.

Also contributing to that misperception is a great deal of propaganda pushed by the firecely competitive shipping companies, whose owners are making fortunes from convincing more and more Europeans to emigrate.10

Like others in Europe, our Lithuanian peasants have heard that in America fortunes can be made, an idea that takes on the proportions of a myth—a moral story, not necessarily based in reality, that organizes a worldview and inspires men and women to action.

This myth is layered with personal tales, of course: stories of success that filter back from people they know, or from someone whom an acquaintance—or perhaps a relative of an acquaintance—knows. Or… claims to know.

Of such uncertain stories are European dreams made of.

One story of success trickling back is that of one Jokubas Szedvilas. People hear that Szedvilas made it big in America—in the stockyards of Chicago. That’s all our protagonist, the young Jurgis Rudkus, knows. And this legend of one man enjoying some success in America gets him excited—and others, too. Clinging to this story, and impressed by the masses getting on ships and leaving Europe, a Europe threatened by famine, Jurgis and a few relatives and acquaintances from his town decide collectively to emigrate together as a solidary group; to tear themselves from Europe and, like storied heroes, strike it across the Atlantic seeking the Promised Land: the stockyards of Chicago!

The problems begin almost at once.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.