InFocus Magazine Fall Edition 2024

Stephen Bryen | Oct 3

President Truman signs the NATO Treaty

President Truman signs the NATO Treaty

Despite efforts to reinforce its presence in Poland, Romania, and Estonia, the alliance faces significant problems: a critical shortage of armaments; untested and undermanned armed forces; and a US presence that is still mostly expeditionary.

Ukraine

Although NATO has expanded and continues to feed arms into Ukraine, the prospect for Ukraine surviving Russian attacks seems poor. Meanwhile, Russia has learned a great deal about how to deal with NATO weapons using its air defenses and electronic jamming capabilities. The cupboards in the United States are noticeably empty as a result of the conflict, and there is no reason to think that, aside from air power, NATO could do any better in Ukraine than the Ukrainians.

NATO is still strident when it comes to Ukraine and its posture toward Russia. Some non-factors such as the European Union are even worse rhetorically. But the new NATO is facing a dire situation in Ukraine and the risk of a wider European war. Will NATO cross the Rubicon of conflict, or seek some accommodation with its sworn enemy, Russia?

The Threat

It is no small matter that the alliance is no longer focused on communism as a threat, but rather on Russia as a threat to Europe (and by extension, to the United States.) The American commitment to Europe puts Washington in a difficult logistical and military position to deal with the far more potent threat of China. But, it seems, US policymakers prefer to deal with the Russian threat – perhaps because that assures US dominance in European affairs and favors American interests.

If Russia was an actual threat, and if the Europeans were really committed to their own defense, then Europe could easily assemble a military force comparable to, if not bigger than, anything Russia could muster. Europe has a population of more than 700 million. By comparison, Russia has a much smaller population (144.2 million), a much smaller economy, and an army of around 470,000 soldiers. (The US Army numbers around 452,000 active-duty personnel).

The Original Threat

The NATO Treaty was adopted in Washington in 1949. Europe was under siege from surging domestic Communism, the Russians had mostly completed their work of taking over eastern Europe and putting Communist governments in place, and the Berlin Airlift was still underway.

Four months after the Treaty was signed, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb (dubbed Joe-1 after Joseph Stalin) ending the US atomic monopoly.

The original members did not include Germany, Turkey, Greece or Spain. Greece and Turkey would join in 1952; Spain only in 1982, well after dictator (Caudillo) Francisco Franco’s death in 1975. Germany was divided and occupied. The Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) under allied occupation (US, UK, and France) was declared in May 1949, but it remained an occupied area until 1955. In May of that year, the FRG joined NATO. In response, Russian-occupied East Germany became a state on October 7, 1949. It would join the Warsaw Pact, or Warsaw Treaty Organization, Russia’s answer to NATO founded on May 14, 1955. NATO and the Warsaw Pact defined the Cold War until the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

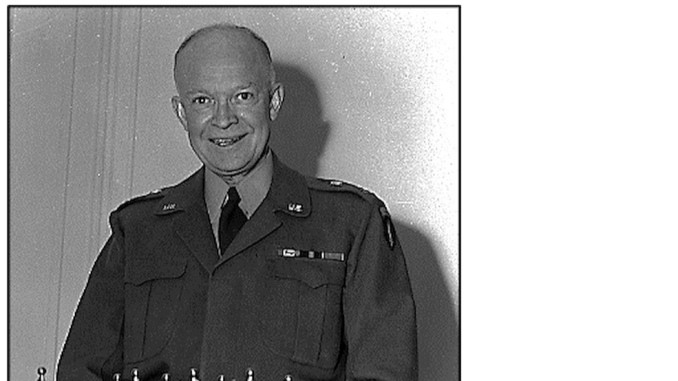

On December 19, 1950, General Dwight Eisenhower became NATO’s first Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). He subsequently activated the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) on April 2, 1951, and began forming his new multinational staff at Roquencourt near Paris, France.

On December 19, 1950, General Dwight Eisenhower became NATO’s first Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). He subsequently activated the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) on April 2, 1951, and began forming his new multinational staff at Roquencourt near Paris, France.

NATO was part of a strong program launched by the United States to rebuild Europe after World War II, end the domestic Communist threat in a number of European countries (Greece, Italy), protect the allied part of Berlin (a divided city), and create strong defenses against any Soviet military threat to Europe. As a result, the US established a permanent military presence in Europe including important bases in Germany, the UK, and Italy. Belgium became the home of the NATO command known as the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, commanded first by General Dwight D. Eisenhower (April 1951 to May 1952).

Article 5

The NATO Treaty defines the alliance as defensive. The key provision, Article 5, states:

The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

Article 5 was only used once, on September 12, 2001, a day after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. A decision was reached, after some controversy, by the North Atlantic Council, the political decision-making part of NATO. NATO carried out a program called Eagle Assist, sending NATO AWACS aircraft to patrol US skies. Although a symbol of support, NATO’s intervention was militarily largely meaningless. What NATO AWACS planes could do in US airspace was never explained.

NATO itself, however, has been involved in a number of operations that used military force – in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Bosnia, and Libya. NATO also is directly involved in Ukraine, though not with ground troops.

The Evolving Russian Threat

After its founding, NATO concentrated on preventing a Russian invasion of Western Europe, mainly focused on West Germany. NATO strategists and outside military experts focused on the idea that the Soviet Union (mainly Russian troops) would invade through the “Fulda Gap,” a lowland corridor running southwest from the German state of Thuringia to Frankfurt am Main that, immediately following World War II, was identified by Western strategists as a possible route for a Soviet invasion of the American occupation zone from the eastern sector occupied by the Soviet Union.

As the USSR built up its forces in the 1970s and 1980, Western strategists worried that the US and its NATO allies lacked enough armor and artillery to stop a Russian attack.

Some of this focus on the Russian threat was reflected in two novels, one written by Sir James Hacket called The Untold Story: The Third World War”(1978) and Tom Clancy and Larry Bond’s Red Storm Rising (1986).

In 1981, KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, in a then-secret speech, said it was critical that Russia “not miss the military preparations of the enemy, its preparations for a nuclear strike, and not miss the real risk of the outbreak of war.” According to Andropov, NATO was preparing a first strike on the Soviet Union under the cover of two NATO exercises, Autumn Forge 83 and Able Archer 83. Minister of Defense Dimitry Ustinov told the Politburo that the NATO exercises were “increasingly difficult to distinguish from a real deployment of armed forces for aggression.”

Just as the United States and NATO feared a Russian attack, Russia seems to have had a mirror image of a preemptive attack on the USSR, focused on nuclear weapons. While Russia and the United States would engage in proxy conflicts over the Cold War Years (Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the Middle East), general war in Europe did not happen.

Collapse of the USSR

In October 1985, Gorbachev, on a visit to Paris, met with Francoise Mitterrand, the French president. He told Mitterrand that Russia was a third world country with nuclear weapons. In 1991, his insight was demonstrated. On December 26, by Declaration No. 142-H of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the USSR ceased to exist.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, left, and French President François Mitterrand after signing the agreement on consent and cooperation between the USSR and France during Gorbachev’s working visit to France.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, left, and French President François Mitterrand after signing the agreement on consent and cooperation between the USSR and France during Gorbachev’s working visit to France.

With the collapse of the USSR, Russian power was radically downsized. The infamous Soviet military buildup of the 1980s, that had sucked the Russian economy dry, was now left rusting away. Nuclear submarines were abandoned in port, slowly sinking in their berths. Defense factories stopped producing. Workers were not paid. For the next 15 years, Russia would be on its heels, struggling to reinvent itself. The Warsaw Pact disappeared.

Russia was now a dysfunctional state with nuclear weapons. The Russian army itself was falling apart. Russian military gear was for sale in flea markets in eastern Europe to earn a few dollars. The West was worried about ex-Soviet scientists hiring themselves out to rogue states, worried about rotting nuclear submarines and unsafe nuclear power plants, unsure about who was in command and, overall, whether Russia was a stable country.

Meanwhile, what remained in Russia was mired in corruption. Even as Russia slowly regained its footing, corruption throughout the country continued, including in the military. As this paper is written, anti-corruption investigations, arrests and firings in the Russian military are taking place as Russia’s leadership tries to upgrade army leadership and improve military equipment and supplies released to the troops.

Post-Soviet NATO Expansion

When the Soviet Union collapsed, NATO still regarded Russia as an existential challenge. That challenge, in the NATO view, took on added gravitas after Russia sent troops into Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014 and 2022). It is easy to overlook the fact that NATO had its own ambitions in Georgia and Ukraine and was actively promoting NATO in both places, including trying to force the Russians out.

Today all NATO military exercises, troop deployments, and operations are focused on stopping a Russian attack. NATO has reinforced its troop deployments and bases to protect the Baltic states (especially Estonia, which NATO sees as vulnerable), Poland, and Romania.

While the USSR was dissolving, NATO started an unprecedented round of expansion. While in 1991 and the following years there was little tangible to fear from Russia, the newly independent states needed defense help. Most had been utterly dependent on Russian weapons, and these would not be forthcoming in future. Moreover, they wanted to be protected. While the Russians, from time to time complained, and on occasion were given assurances that proved false, NATO expanded.

NATO also embarked on programs to offer future NATO membership to Georgia and Ukraine. The offer came with NATO advisors and specialists, weapons, and intelligence support. Russian leaders saw the attempts as threats, especially when it came to Ukraine. NATO, along with the EU, put pressure on Ukraine to join Europe and separate itself from Russia. For its part Russia saw NATO in Ukraine as a visceral threat to Russian security.

Along with NATO expansion was the aggressive stance of the alliance beyond its defensive mandate. That includes operations in Afghanistan’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), Bosnia and Herzegovina Implementation Force (IFOR), Kosovo Force (KFOR) and Libya (Operation Unified Protector.) The US tried to get NATO to support the Iraq war (2003) but could not, with Turkey strongly opposed. Instead, the US created a “Coalition of the Willing” (Multinational Force, Iraq) with troops from the US, Australia, UK, and Poland). Other states would subsequently send contingents to Iraq to support stabilization efforts.

Ukraine Again

NATO’s future is inextricably linked to Ukraine. As the war reaches an end point with Kiev potentially forced to deal with Moscow, Ukraine’s defense minister is working hard to convince Washington to give Ukraine long range weapons to attack Russian territory, especially Moscow and St. Petersburg. The Ukrainians know very well that if Washington cooperates fully, the Ukraine war will invite even more violent Russian attacks. They are counting on this to draw NATO in and have NATO troops replace Ukrainians on the front line. It is easy to understand that if NATO actually sent troops or brought NATO air power to bear on Russian operations in Ukraine, the war would rapidly expand to Europe.

This lifeline for Ukraine would put NATO in the eye of a storm to which it has already contributed in many ways. Could NATO be dragged into a war that will threaten European cities, infrastructure, and military bases? Despite the Ukrainian push into the Kursk area of Russia, and large-scale drone attacks on Russia including shelling of civilians in Belgorod, the Russians have not taken the bait other than to continue to put pressure on Ukraine’s army (AFU). Most reports are that Ukraine’s army is overstretched, short on manpower, and starting to crack.

The question is what is next?

Hi, Edgar

India, Pakistan and Philippines have had border clashes — minor events compared to what’s happening in Europe, Africa and the Middle East; but yes, of course, They are all part of one great war, with the same main actors.

Michael-

What about India, Pakistan, Sth. Korea. Philippines, Australia………../???

Ted,

My post seems to have disappeared.

Hi, Edgar

It’s also of no interest to me, who invaded whom. Here’s my short list of who’s involved:

Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Armenia, NATO, Israel, Iran, North Korea, Mexico, several drug cartels, Yemen, Lebanon Sudan, Mali, other African actors…

and itching to get involved, it seems, China.

That list includes all the world’s powers, from every corner of the world — a de facto world war.

I can imagine this conflict going one of two directions: 1. a world war involving every ocuntry of the world, or 2. The current situation resembles the face-off around 1942. I think the biggest problem then, was that every party thought they could win.

MICHAEL-

I’m sure I haven’t made a single post on this subject as apart from an initial observation that it is Russia who invaded, not vice-versa.

And that was a few weeks into the beginning of the fray.

It is of no great interest to me.

Peloni, Ted, Edgar, etc., you’re playing devil’s advocate, continually taking up Russia’s point of view. Adam, Bear and and all have taken on the NATO side. So far, we’ve come up with a stalemate. It would be nice, if we could operate effectively as a think tank. To whit, I wonder if we could use our observation and deduction, to come up with some real, workable solution to facilitate a peaceful to the near-nuclear war we have all gotten entangled in.

I suggest that we begin by

1. deciding that we actually ARE in a world war.

2. determine who the actors are.