E. Rowell: The Obama Administration responded to a 2012 conflict in the South China sea by “mediating’ between the Philippines and China. The end result was the the Philippines went back to their shores, but China stayed in the Scarborough Shoals. Right where they were during the conflict*. It is unclear what the Biden administration’s response would be to provocations by China at this time. Judging by foreign policy past performance, the Biden Administration appears to effect foreign policy that is destructive to US interests and puts our enemies’ needs first. We can see this play out in the conflict with Russia, in which the US overtly appears to want Russia destroyed, but the effects of Biden’s policies has been to destroy the US economy and potentially to destroy NATO itself. Biden policy in the Middle East also is geared to meeting the needs of Hamas, Iran, Qatar, Egypt, and Hezbollah, at the expense of Israel and US defensive deterrence in the land and waters of the Middle East.

US-China tensions, with Philippines in the precarious middle, may be drifting toward a ‘1914’ moment in the disputed waters.

By Bob Savic, ASIA TIMES 4 June 2024

Chinese vessels gather near Whitsun Reef in disputed waters also claimed by the Philippines in the South China Sea in December 2023. Photo: Philippine Coast Guard

China’s announcement of its intention to enforce a law that would arrest foreign nationals venturing into waters it claims in the South China Sea (SCS) may be the trigger for a direct military confrontation with the United States. The regulation, known as the Administrative Law Enforcement Procedures for Coast Guard Agencies, will come into force on June 15, 2024.

Violent incidents between US ally, the Philippines, and China, have been ratcheting up in recent months. Dramatic film footage by Britain’s Sky News showed several large Chinese Coast Guard vessels pounding a smaller Philippine Coast Guard ship with powerful water cannons in disputed waters surrounding the Scarborough Shoal.

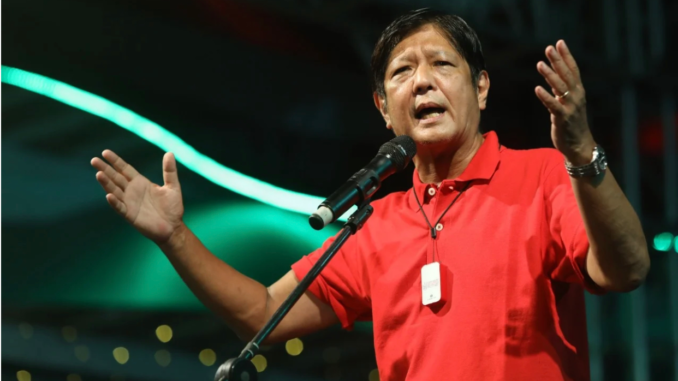

Shortly before, US President Joe Biden met with Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in Washington DC to discuss regional security. Biden affirmed “iron-clad” support for the Philippines under the auspices of their mutual defense treaty, including protection of coast guard vessels that come under armed attack in the South China Sea.

Since the treaty requires that an “armed” attack be reported to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in the first instance, China’s use of water cannons, even though potentially lethal, has to date not been construed as such. Certainly, the Philippines did not submit a report of the Sky News-filmed incident to the UNSC.

Nonetheless, at the Shangri-la Security Dialogue in Singapore held at the end of May, Marcos stated “If a Filipino citizen was killed by a willful act, that is very close to what we define as an act of war. Is that a red line? Almost certainly.”

This red line will become even redder from June 15 as any arrests made under China’s enforcement of its new law are likely to be carried out at gunpoint, heightening the risks of a deadly incident.

Philippine leader Ferdinand Marcos Jr sees red lines in the South China Sea. Image: Twitter

Marcos Jr has characterized China’s enforcement of the law as “escalatory” and “different” from anything Beijing had previously imposed in the contested and strategic maritime region, of which China claims nearly 90% under its nine-dash line.

Should Manila be forced to invoke its mutual defense treaty for American assistance, it would not be hard to imagine Chinese coast guard vessels being quickly confronted by US warships currently patrolling the region to enforce freedom of navigation.

Biden would likely have to respond affirmatively in that event, otherwise risking concerns from already nervous American allies with whom Washington has formal security pacts – not least being the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Moreover, in underscoring Washington’s focus on the Indo-Pacific at a time of spiraling tensions in the South China Sea, US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin stated at Singapore’s Shangri-la Dialogue that “despite these historic clashes in Europe and the Middle East, the Indo-Pacific has remained our priority theater of operation.”

In turn, Chinese Lieutenant General Jing Jianfeng scornfully replied that the US Indo-Pacific strategy was intended “to create division, provoke confrontation and undermine stability.”

In light of Austin’s pronounced refocus on the Indo-Pacific, it seems likely that any request for US military assistance by the Philippines would be viewed positively in Washington, probably gaining overwhelming bipartisan support from Democrats and Republicans in Congress.

Interestingly, one of Washington’s staunchest allies, the United Kingdom, having significant naval resources deployed in the South China Sea, may be girding itself for such an eventuality.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s sudden and unexpected announcement of a July 4 election date – at the very least signifying Britain’s shared interests with those of America’s on its Independence Day – came in tandem with a proposal for national service, ostensibly in preparation for war and possibly in particular in the South China Sea.

Aside from the disastrous global financial and economic shock waves likely to arise from any direct US-China military confrontation, it may be a conflict Washington is preparing for, subject to one principal constraining factor: any direct military confrontation being contained exclusively within the South China Sea region.

It may not be such a far-fetched scenario when one considers the 1950-53 Korean War. During this conflict, around two million US servicemen fought fierce battles against three million Chinese and 100,000 Soviet troops, alongside their respective South and North Korean allies.

Yet it was a conflict contained by then-US, Chinese and Soviet leaders, Truman, Mao and Stalin, respectively, within the territorial limits of the Korean Peninsula, deliberately avoiding spillover into the broader global context of the then-young Cold War.

Hopefully, ongoing diplomacy in various areas of cooperation between the US and China will prevail and a direct military conflict, including a limited theater war, will be averted. But a peaceful outcome should not be taken for granted.

Tensions in the South China Sea, not to mention nearby Taiwan, are escalating almost by the day. Trade frictions between Beijing and Washington are also ramping up with ever more sanctions on US tech exports to China amid new punitive tariffs on imports of Chinese green technology including EVs.

Meantime, accusations over Chinese President Xi Jinping’s support for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Ukraine war appear to be intensifying in Western circles. These include the UK Defense Secretary’s still unsubstantiated claims of direct Chinese military supplies to Russia.

Additionally, US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell has claimed that Chinese support was effectively reconstituting Russia’s military in the form of drones, artillery, long-range missiles and tracking of battlefield movements.

“This is a sustained, comprehensive effort backed up by the leadership in China that is designed to give Russia every support behind the scenes,” Campbell stated during a visit to Brussels at the end of May.

One cannot merely sweep aside the dangers emerging from US-China rivalry on multiple fronts, much as they did in the lead-up to the First World War as European powers jostled for supremacy on the continent.

Chinese Coast Guard ship uses water cannons on a Philippine navy-operated supply boat as it approaches the Second Thomas Shoal in the disputed South China Sea on December 10, 2023. Photo: Philippine Coast Guard

In today’s equally polarized and militarized environment, it is vitally important to identify and calm any potential trigger points, whether accidental or not, that may explode into a catastrophic, earth-shaking regional conflict.

The trigger for the First World War occurred on June 28, 1914, with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in a country in Southeast Europe. This time, the trigger could be the death of a Filipino sailor in the tropical waters of Southeast Asia.

The US and China must ensure they don’t sleepwalk into a repeat of the 1914 tragedy in the second half of June 2024 or, indeed, at any point in the future.

* Strategic Failure, by Mark Moyar, Chapter 15

Bob Savic is Senior Research Fellow, Global Policy Institute, London UK and Visiting Professor, School of International Relations and Politics, University of Nottingham UK.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.