E. Rowell: While American Jewish University students were not in Israel during the 7th of October holocaust, they experienced what Jews in Nazi Germany began to experience before Jews were actually rounded up and imprisoned. The subversion of American education over multiple generations since the late 1920’s and 1930’s is near complete. Cultural Marxism has brought about division, polarization into oppressed vs. oppressor groups, and “cancellation” of the so-called oppressors: Jews are to be shunned, humiliated socially, and made to feel unwelcome in society. Both Hitler and Stalin would approve.

By The Editors, TABLET MAGAZINE 23 May 2024

Campus cleanup at UCLA in Westwood, California, on May 2, 2024 /BRIAN VAN DER BRUG/LOS ANGELES TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

Campus cleanup at UCLA in Westwood, California, on May 2, 2024 /BRIAN VAN DER BRUG/LOS ANGELES TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

For Jewish American college students, last fall began with optimism: finding old friends on campus, new books stacked on dorm-room desks, curiosity about the semester to come.

But what followed the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7 crushed that optimistic spirit: Zionists are not welcome. Go back to Poland. Be grateful that I’m not just going out and murdering Zionists. Jewish students across the country were targeted and vilified; they lost friends; in some cases they were told by administrators that their safety could not be ensured.

To mark the end of a year like no other, we have collected short reflections from college students across the country. These are not stories about Israel but about America; they are not about the war in Gaza but the one at home.

Ronnie Volman

University of California, San Diego

Ronnie Volman is a freshman at University of California, San Diego.

I was born in Israel and have been living in the United States since I was 3. On Oct. 7, as I frantically read the news, a friend on campus told me the attack was my fault and that I am directly “responsible for bombing kids.” Another classmate told me that I can’t possibly be peaceful because “Zionists are genocidal.” Yet another tried to insist that they don’t hate all Jewish people, just the Jewish people of Israel.

The vast majority of my friends and family reside in Israel. Despite being over 7,000 miles away, I remain very close to them. I am in frequent contact with my friends, some of whom have to face the reality of enlisting in the IDF in the upcoming months, while I have the privilege of studying in the United States. I distinctly remember the immense anxiety taking shape as I received WhatsApp messages on Oct. 7 from family and friends living in central and south Israel. The anxiety never truly disappeared, with the importance of their safety being something that I think about constantly.

Following Oct. 7, I lost countless friends and peers on campus for standing up against the undeniable rise in antisemitism, with my lived experiences as a Jewish person repeatedly undermined. I have been shunned and ostracized by a campus community that I once trusted to be an inclusive, open-minded forum for discussion. My former friends have deemed me to be a supporter of genocide, a colonizer, and an aggressor for not hiding my identity as an Israeli student. Rather than forming a ground for compassion, words such as “Zionist” and “Israeli” are now thrown around as insults.

Not a day goes by that I don’t think about the hostages, especially those that are closer to my age. While there are respectful disagreements over the nuances of politics, I have found solace in the sympathy expressed by close friends about the safety of my friends, family, and the remaining hostages.

My family escaped the Soviet Union to build a new home in Israel. The lived experiences of my grandparents as openly Jewish people in the Soviet Union now regrettably resonate with me, as I navigate my identity as a Jewish student. They fled, hoping that their children and grandchildren would not have to endure the same confrontations with rampant antisemitism. A bridge from the past to the present, I grew up listening to stories about their struggles to live openly and without fear. Now, when I FaceTime my grandmother, she shares expressions of disbelief and dismay over distant echoes of her past that have manifested into my current experiences as a student on campus. For the first time—and this is something that I am ashamed to admit—I am scared to live my life as a proud Israeli and Jewish person.

Mimi Gewirtz

New York University

Mimi grew up in Minneapolis. She is graduating from NYU’s Gallatin School.

On Sunday, Oct. 8, I found out that Hersh Goldberg-Polin was abducted by Hamas. Though he lost half his left arm to a grenade while protecting a bomb shelter packed with other civilians, there was some evidence he was being kept alive in the tunnels beneath Gaza.

Hersh was my classmate for the two years I attended school in Jerusalem during my parents’ sabbatical. Hersh had moved to Israel with his family from Virginia around a year before I met him. On Oct. 9, I posted Hersh’s picture, asking for information, on my Instagram Story along with a picture of his bedroom with a “Jerusalem for All” poster plastered on his wall. Within a few hours, I had lost 50 followers. Posters of Hersh and the other hostages started to appear on campus walls and windows. A week later they were being torn down.

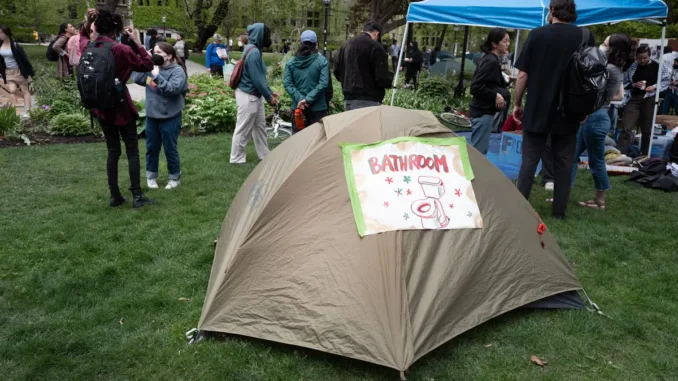

Bathroom tent at the University of Chicago tent encampment, April 29, 2024/SCOTT OLSON/GETTY IMAGES

Bathroom tent at the University of Chicago tent encampment, April 29, 2024/SCOTT OLSON/GETTY IMAGES

I have family and friends in Israel. Some have spent most of the past seven months on reserve duty. As a progressive, I am someone who believes in the fundamental right of Israel to exist but opposes the actions of its current government; someone who is desperate to see the darkest period in the history of Israelis (Jews and Arabs) and Palestinians end. For me and people like me, opportunities for dialogue on campus have gone from fraught to virtually nonexistent. I want to be able to mourn the loss of lives and call for a cease-fire together with those protesting, if at the same time I could openly carry a “free the hostages now” poster. I want to express my empathy for the loss of life in Gaza, but not if I have to stand next to a banner that says that Oct. 7, the abduction of Hersh, was resistance.

While the most aggressive protesters defend themselves on free speech grounds, our ability to engage in real dialogue is continuously shrinking amid the fear of giving offense. I have always been cautious about who I can talk to about these issues. But since Oct. 7, that circle has shrunk to a vanishing dot. College was sold to me as a “marketplace of ideas.” On my campus, however, nuance was the first casualty in a war of slogans and intimidation, and I have come to live in a tiny bubble, not unlike the days of COVID.

I am thankful for non-Jewish friends who understand my fears. They are my eyes and ears. One warned me to avoid the library after seeing a group angrily cheering for an “intifada.” Another said she herself was leaving a class after the professor promised the students he would never give them anything to read that was written by “settler-colonialists.”

It was a painful irony that I recently found myself watching a group of faculty protesters occupying the campus library, a supposed bastion of contemplation and learning, to loudly denounce Israel and anyone who will not renounce it entirely. I feel lost in the noise. There are no more quiet places where we can hear one another speak.

Yola Ashkenazie

Columbia University

Yola is a graduating senior in Barnard College’s dual-B.A. program with the Jewish Theological Seminary where she studied psychology, economics and Jewish texts.

I was at dinner with my roommates when a text came in. “I assume you saw the photo of you on Barfnard’s Instagram?” My heart sank. I hadn’t. What photo?

I was aware that this Instagram account, associated with Students for Justice in Palestine, only posts photos of people and things that they hate. I hastily grabbed my phone and opened my Instagram app. It was a photo of me with Israeli flags. The insinuation was that I was deplorable because I appeared alongside Israeli flags. I brushed it off, assuming it might not reach many people or that most wouldn’t care much.

I was wrong. The next day, on my way to psychology class, a student stopped me. “Oh, you’re that girl,” she said. Confused, I looked back at her, and she casually added, “You know, that one that supports genocide.” With that, she continued walking. Just a few minutes later, in class, a friend asked if I had checked Sidechat, Columbia’s anonymous social-media platform. A pang of fear hit me as I opened the app and saw posts about me. “That freak show girl from the news and Barfnard,” read one. “ZioTerrorist,” read another.

While concerned friends and family warned me to be afraid of this sudden attention, what I felt was not fear but sadness. Not for myself, but for the end of productive conversation and meaningful discourse on my campus. Since October, I had been trying to convey that the loss of innocent life in both Israel and Gaza is a profound tragedy. I pleaded on national television that advocating for one group should not come at the expense of another. But it is evident that no one on campus hears me. My support for Israel has caused my peers to shut down, not listen. My support for Israel and my criticism of Hamas had branded me a baby killer and a genocide supporter.

Now I have a recurring dream. In it, President Rosenbury calls my name, and I walk across the graduation stage at Radio City Music Hall. Instead of cheers, the entire crowd boos me. I look out into the audience and recognize faces—friends, or rather, former friends. Sorority sisters, or perhaps former sisters. People who have unfollowed me on Instagram and sent hateful DMs all year long. And the boos keep getting louder until I wake up.

Talia Elkin

University of Chicago

Talia Elkin is from Teaneck, New Jersey, and is currently a student at the University of Chicago.

My peers at the University of Chicago are some of the nation’s best and brightest young minds. They’re also shitting in tents.

The beige pop-up tent, which served as my classmates’ makeshift commode, consisted of a bucket and some kitty litter. Somehow it was hardly remarkable in situ, surrounded by a hodgepodge of other tents, tables, and banners. Nearby was the medical tent, which, according to an Instagram post, was trying to provide essential supplies like tourniquets, ChapStick, condoms, and HIV tests. After all, as Karl Marx famously said, the revolutionaries “have nothing to lose but their chains and their virginity.”

KATIE MCTIERNAN/ANADOLU VIA GETTY IMAGES; ALLISON BAILEY/MIDDLE EAST IMAGES/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

KATIE MCTIERNAN/ANADOLU VIA GETTY IMAGES; ALLISON BAILEY/MIDDLE EAST IMAGES/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Thirty years from now, my friends’ firsthand accounts of rabid university antisemitism will be my kids’ history lesson in school. My kids will ask me about it over dinner: Were college campuses really that scary? I will say yes, because it’s true. And I will tell them how a sea of my educated classmates cheered for an intifada, justifying Oct. 7 again and again.

But I also know that when I reflect on my junior year of college, sitting at the kitchen table with my kids, I’ll end up shaking with laughter. Because sometimes Jewish history can feel like an endless loop of suffering. Our people have faced so many enemies and hardships, have come close to extinction, and have known suffocating and unrelenting fear. The Poop Tent, though; this is something new.

Joey Kauffman

Williams College

Joey Kauffman is a member of the class of 2027 at Williams College. He is a prospective English major and a member-at-large at the Williams College Jewish Association.

At 9:40 a.m. on Thursday, May 2, I went to Paresky, Williams’ student center, to get some coffee. I had about an hour to spare before class, and I needed some caffeine. But as I was leaving Paresky, I saw someone doing something that I had never actually seen in person before: Someone was taking down hostage posters.

There were around six posters that displayed the names and photos of hostages taken by Hamas on Oct. 7. If I remember correctly, one of the hostages on these posters was Thai. The others were Israeli. Many of them were likely Jewish. Some of them looked Ashkenazi while others looked more Mizrahi. On Oct. 6, these people were living normal lives. And on Oct. 7, these people and others experienced something so frightening that it goes beyond comprehension.

While the geopolitics of the Middle East is certainly an intensely complex arena, these victims of Oct. 7 were not to blame for the political structure of the Middle East. They were just people. But these victims of the Oct. 7 attacks were the ones who were tortured, maimed, and raped because of the complex historical situation that they happened to be born into. On Oct. 6, these people had lives, they had loves, and they had hopes and dreams. And on Oct. 7, these people were victims of inexplicable terror. The lives they had known slipped away within a day.

For a moment, I just looked at the person taking down the posters. They were taking them down with speed and efficiency, as if this was just another part of their day. They took down the posters in the same way that I had gotten coffee in Paresky: It was just another thing on the to-do list, another task to get through.

I looked out into the crowd of students rushing past Paresky. I looked around for someone to stand up and ask this person why they were taking the posters down.

But no one did. I made eye contact with a Jewish friend of mine, someone who I know has family members in Israel and is scared about their safety. I mouthed the words “What the f–k” to him. I then realized that maybe I was supposed to be the one to say something to the person taking down the posters.

I asked if they could keep the posters up, saying that they were compliant with school rules and allowed to be there.

The person looked back at me, completely calm. They refused and said that the hanging of the posters tried to justify the genocide of Palestinians.

I said that I didn’t put the posters up but that these hostages are innocent victims.

They were already nearly done taking the posters down. “They’re settlers,” they said, and walked away.

I tried to think of something, anything, to say to express the pain in my heart in that moment. But I couldn’t say anything. I just couldn’t.

Sabrina Soffer

George Washington University

Sabrina Soffer is a senior at the George Washington University where she is pursuing a double major in philosophy with a public affairs focus and Judaic studies. She also served as the commissioner of GWU’s antisemitism task force.

Entering college, I envisioned myself as a champion of social justice. Now, that ideal has taken on a complex new dimension—from which I am excluded. In classrooms, my perspectives are often labeled “racist” and “xenophobic.” Some peers even refuse to engage with me, blaming me, as an Israeli and a Jew, for the suffering of all Palestinian people.

The above is not isolated to me. It all began with pervasive rhetoric in classrooms, online platforms, and public spaces. Soon, our campus was littered with posters and electronic graffiti bearing hateful messages: “Zionists fck off,” “Settlers, fck off,” “Free Palestine from the River to the Sea,” “Glory to our martyrs”—thinly veiled calls for the destruction of Israel and the celebration of mass murder. Then came demonstrations echoing deliberate calls for violence: “There is only one solution, intifada revolution!” Sometimes protesters would add that this is “the final solution.”

Today, my friends and I find ourselves physically excluded from a so-called “liberated zone” on campus: an encampment exclusively for those who disavow the idea of a Jewish homeland. Self-proclaimed social justice warriors have cornered and spit on us, followed us around with cameras, and threatened to kick us off campus. When they say, “We want no Zionists here,” they really mean it.

When I introduce myself to peers on campus as an Israeli and Jew, I feel that I am immediately associated with evil, crime, and shame. How is this social justice?

A woman attending a George Washington University rally against campus antisemitism holds a placard in a park in downtown Washington, D.C., on May 2, 2024/ROBERT SCHMIDT/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

A woman attending a George Washington University rally against campus antisemitism holds a placard in a park in downtown Washington, D.C., on May 2, 2024/ROBERT SCHMIDT/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Alexandra Orbuch

Princeton University

Alexandra Orbuch is a junior at Princeton University studying history. She currently serves as publisher of the Tory, Princeton’s journal for conservative thought.

Just weeks after the attacks of Oct. 7, my classmates at Princeton called to “globalize the intifada” from “Princeton to Gaza,” urging violence against Jews on this very campus. They chanted, “There is only one solution: intifada, revolution.” Willing to align themselves with terror movements, Princeton’s Students for Justice in Palestine hosted a “Kick-off Rally for Divestment From Israeli Apartheid” with Samidoun, a network advocating for the release of Palestinian prisoners that is an affiliate of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a U.S.-designated terrorist organization.

During a protest at Princeton last fall, I was pushed by a protester while attempting to cover an anti-Israel demonstration in my capacity as the editor-in-chief of Princeton’s conservative journal. In the aftermath of the assault, I reported the incident to the university, but the investigation was dismissed, and the decision was “not subject to appeal,” according to Princeton’s vice provost for institutional equity and diversity. Not only did Princeton fail to discipline the protester who pushed me, but it also allowed him to take out a no-contact order (NCO) against me. Under this order, I was advised that “[t]he safest course of action in terms of a possible violation of the NCO would be to refrain from writing or to be interviewed” for articles about the assault. Speaking out about what happened to me could be construed as “an indirect or direct attempt to communicate,” I was told. In other words, turning to the media for accountability would be dicey unless I wished to risk disciplinary action—or worse. Only once I contacted the Anti-Defamation League and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and they issued a letter to my university president, was the NCO removed. Without the pressure provided by outside legal assistance, I would still be silenced today.

I came to Princeton in search of a rigorous education, and I have received that. But I have also received a clear message from my own campus that free speech protections are doled out only to those with views that the university favors: For those of us with disfavored viewpoints, it’s open season for harassment and intimidation.

Ilan Listgarten

Connecticut College/Paris

Ilan Listgarten is a 21-year-old college student from San Mateo, California. He is a junior at Connecticut College with a double major in international relations and French. He specializes in Jewish advocacy and environmental policy.

I grew up in what I now recognize as an incredibly safe time and place for me to be Jewish. I remember when my hometown synagogue in the Bay Area had no guards at the door, and have watched as they added one guard and then two, erected 5-foot fences and then 10-foot ones. I’ve felt the difference between openly expressing pride in my Jewish identity and feeling as if I have to hide it. Post- Oct. 7 has exacerbated the antisemitism, but I had already felt the undercurrents.

I study French and international relations with a research focus on French-Jewish affairs at Connecticut College. Following Hamas’ attacks on Israel, my campus was eerily quiet. The terrorist attack was not acknowledged by my professors or my classmates. The week of Oct. 7, everyone continued with normalcy. My classmates answered questions about our latest readings, as I sat in my classes frantically refreshing my WhatsApp messages to find out if my friends in Israel were still alive. The only acknowledgment from my non-Jewish classmates I saw was a girl who wore a Free Palestine shirt on Oct. 8. For the rest of the semester, I was in shock. In the spring semester, I traveled to France to continue my studies abroad at Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris-3.

In Paris, my experiences have varied. I live in a Jewish area with a host family. I have attended various synagogues. The first time I wandered for an hour before finding the entrance hidden amid a group of inconspicuous buildings. The second time, I attended a more prominent synagogue where the entrance was guarded by a dozen heavily armed police officers. As I left the service, the police told me to take off my kippah. In talking to French Jews at synagogue and Passover, I heard stories of them being spit at, called slurs, and forced to practice their religion quietly. I realized these events, this struggle, and hardship to be Jewish, was new for me and perhaps many Americans, but it is not new in France.

From France, I watch as friends, classmates, and colleagues post on social media blatant hate speech, whether knowingly or unknowingly, with tags such as “from the river to the sea Palestine will be free” or “globalize the intifada.” A recent statement signed by an overwhelming number of professors at Conn uses language such as “Jewish supremacy,” describes the war as a “genocide,” and claims that Zionism is NOT “part of Jewish shared ancestry and religion.” I am left feeling abandoned by my peers and my professors and increasingly isolated from spaces that felt like home just eight months ago. I feel powerless and so far removed watching the undercurrents turn into this unstoppable cascading show of antisemitism.

The protests in France have increased. Recently there was a protest outside of my French university. My stomach twisted in knots as I heard chanting, and then saw the origins of the noise. Dozens of students were blocking the entrance with a large sign that read “Sionistes hors de nos facs”—Zionists out of our universities. I decided not to go to school that day.

https://www.jpost.com/international/article-802519