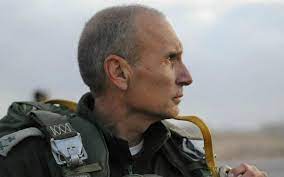

For the past two decades, Gershon Hacohen has been a lonely dissenter in the highest ranks of the IDF. Unfortunately, he was proven right.

Four-and-half months after Hamas commandos overran the police station in the center of Sderot, all that remains is a dusty lot of twisted rebar. Although the city’s police killed over two dozen terrorists before the IDF arrived late in the morning of Oct. 7, it took over a dozen tank shells to bring down the hijacked station, where outnumbered officers had fought Hamas’ Nukhba forces to a bloody impasse. An Israeli tank had never fired on an Israeli building on Israeli territory in combat before.

A freshly painted mural next to the former site of the demolished station memorializes this unprecedented breach in the national reality of the Jewish state: A tank is shown bombarding the building against eerily colorful skies. The numinous image of an open Torah scroll hovers above the scene, recalling the desecrated happiness of the holiday on which the fighting took place. On the day I visited, earlier this month, an American family was on a guided tour, feet away from a group of several dozen uniformed policemen who were also on some kind of organized visit to their force’s newest national shrine. On Feb. 11, the Times of Israel reported that rubble from the station, which was bulldozed the morning of Oct. 8, had been dumped in a nature preserve north of the city.

Is the Sderot battle something to be canonized or buried? It isn’t surprising that the answers, as expressed in the present, are so bizarrely incoherent. One of the major features of the war that began on Oct. 7 is its persisting lack of clarity. Israel might be on the verge of defeating Hamas in Gaza—or it could be weeks away from the steep strategic setback of American recognition of a Palestinian state. While the demobilization of reservists and a newly announced government timeline for the repopulation of the Gaza border region has partly relieved the feeling of an active emergency, an even worse crisis looms in the form of a potential war with Hezbollah, a threat that has so far prevented 60,000 displaced Israelis from returning to their homes in the north.

Months after Hamas’ destruction of a 30-year-old illusion of a settled national existence and the discrediting of most of those responsible for theorizing and implementing it, there is societywide consensus on the need to defeat Hamas and a fog over nearly everything else. There are relatively few senior Israelis left who have proved themselves qualified to see through the morass. Of those few remaining former generals, government ministers, and agency heads still worth listening to, almost none held as senior a position in the security apparatus as Maj. Gen. (Res.) Gershon Hacohen.

In 2000, when Hacohen was the head of the IDF general staff’s training and doctrine division, he was asked to produce a paper about how Israel could defend itself without control of the Jordan Valley, which was to be ceded to a future Palestinian state under peace plans that Prime Minister Ehud Barak, nearly the entire top leadership of the IDF, and the next decade’s worth of Israeli leaders did not think were irresponsible. “My paper was very short: It is like asking an F-15 pilot to just rise up without an engine,” he recalled. “No way.”

In the years before his retirement from active duty in the mid-2000s, Hacohen, who was also the commander of Israel’s national defense college, emerged as one of the IDF’s strongest and highest-ranked internal dissenters. Hacohen, now 69, claimed to me that he was the only active-duty general to accurately warn about the likely security consequences of the 2005 disengagement from Gaza, an operation he was then put in charge of.

In a war game in April of 2005, four months before the withdrawal, the IDF general staff simulated a scenario in which terrorists in the coastal strip launched rockets at Ashdod, Sderot, and Ashkelon. Hacohen’s advice in the midst of the exercise was to tell Prime Minister Ariel Sharon that “we don’t have a full way to retaliate because we will not be allowed to cross the border every week, we will not be allowed to launch artillery at a refugee camp of 50,000 residents, we will kill uninvolved people … therefore tell him what will happen will be a disaster, and we will not have a good way for retaliation.” After giving this assessment, Hacohen said he “was warned by chief of staff,” Moshe Ya’alon, “that I was speaking politically. I told him: ‘I am the only one here speaking professionally.’”

Hacohen was given a monthlong time frame for the removal of Gaza’s 9,000 remaining Israeli civilians, a job he finished in only two weeks. “Why did I succeed?” he asked. “Because I convinced the settler leaders to join me, to understand that they must struggle, but not to the fatal end, because in that way they will lose that legitimation they needed for the main battle about Judea and Samaria.” No soldiers died implementing the withdrawal, the settlement movement retained its credibility in Israeli society and dramatically grew in power, and there were no subsequent unilateral Israeli pullouts from the West Bank.

Hacohen is active in the Bitchonistim, an organization of over 20,000 former security and defense officials who are opposed to any overly risky concessions to Israel’s enemies, most notably the Palestinians. In 2022, the organization presented a detailed security assessment in which it argued for the strategic necessity of forcibly disarming the Gaza Strip. Yoav Gallant, the current minister of defense, attended the launch event for the paper—retired Gen. Amir Avivi, the Bitchonistim’s founder, worked closely with both Gallant and Hacohen when he was in the army. Members of the Bitchonistim are perceived, fairly or unfairly, as having access to the current government, which has informally drawn on their advice over the course of the war.

Israel is a country where ex-generals, including the quietly influential ones, have no particular aura to them—within the martial and Jewish-flavored egalitarianism of Israeli society, a former member of the general staff could be mistaken for a professor or a farmer or a bus driver. Hacohen is different even from the typical run of Israeli former officials. He speaks in a hypnotically slow, even, and high-pitched English, and the spindly retired officer often looks and sounds like a poet or a desert hermit who only happened to have commanded men into battle for over 40 years. I met him late on a Thursday night in Tel Aviv in mid-February, at a mostly deserted cafe near the Defense Ministry headquarters. A few hours earlier, protesters had blocked traffic in front of the ministry, demanding new elections and an immediate hostage release deal, even though there is no realistic one on offer. The demonstration was the city’s one glaring pocket of abnormality: Dizengoff was packed even beyond pre-conflict levels; my hotel in Ramat Gan was at capacity with Israelis heading to a concert at nearby Menora Mivtachim Arena.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.