T. Belman. I wrote about Russia in these articles.

RUSSIA AND THE NEW ME -Part IV: Can Russia be induced to use its UN veto to protect Israel

Prof. Jonathan Sarna of Brandeis University, the preeminent historian of American Jewry, commented on my recent article in The Jerusalem Report, “The divide between US and Israeli Jewry.”

He pointed out that Jews from the FSU (Former Soviet Union), some 1.5 million in Israel and 750,000 in the US, do not fit neatly within the Israeli or American Jewish Diaspora pattern. To more fully understand the American Jewish Diaspora and contemporary Israeli Jewry, one has to consider the profound influence these Israeli and American citizens from the FSU and their descendants have had on their respective countries. Their significance is an underreported story.

The story of their heroes, refuseniks, who risked life, family, and careers fighting to leave the Soviet Union for a life of freedom, is largely unknown to younger American Jews, with the possible exception of the extraordinary Natan Sharansky. The stories of these human rights legends, who have profoundly influenced Israeli society, politics, and American Jewry, are underestimated. The one exception is the world of hi-tech.

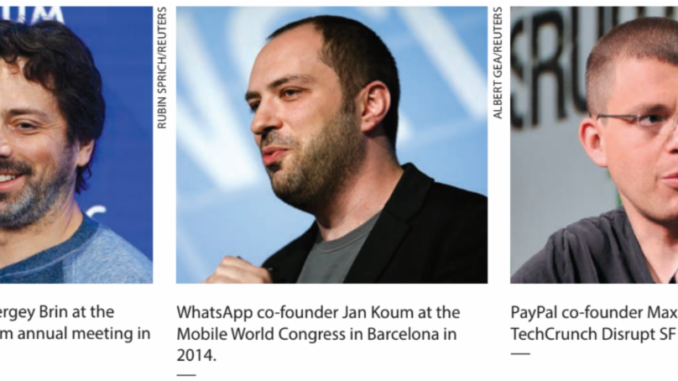

As Cnaan Liphshiz wrote in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), Jews from the FSU in the hi-tech industry have had a “vastly outsized footprint. People like Sergey Brin, Jan Koum, and Max Levchin — co-founders of Google, WhatsApp, and PayPal [respectively]– are just a few well-known examples of how thousands of Jews from the FSU have been at the forefront of the information revolution, many of them having immigrated because of antisemitism…. For this success story, many Russian-speaking Jews credit very hands-on parents who pushed them to excel in overcoming institutional antisemitism. Paradoxically, this antisemitic bias contributed to their ability to excel.” American Jewry can undoubtedly relate to zealous mothers pushing their children to succeed.

According to Gabi Farberov of Limmud FSU, “Russian-speaking Jews throughout history, and today especially, have proved to be pathfinders of advancement in all spheres — the sciences, culture, and business initiatives.”

The purpose of this article is not to be an all-encompassing exploration of immigrants from the FSU in the US and Israel. The goal is to raise the American Jewish Diaspora’s awareness of their continuing influence and make the case that to truly understand Israel and Diaspora Jewry, you must understand these immigrants, their cultural roots, and the traumas they suffered, which continue to influence their younger generations.

While half of Israeli Jews identify as secular (hiloni), four out of five FSU-born Jews in Israel identify as non-religious. For an American Jew who thinks secular Israelis identify with liberal ideology, shining a light on secular Russian Jews is a confounding experience, as these immigrants and their children lean politically to the Right.

Although religiously secular, they strongly identify as Jewish by peoplehood and nationality. Unlike progressive American Jews, Russian Jews strongly support Israel. As Sarna wrote, “The fact that Russian-speaking Jews continue strongly to uphold the central tenets of Jewish peoplehood – expressing strong feelings of attachment toward fellow Jews and the State of Israel – opens up an opportunity at a time when so many young native-born American Jews appear to be spurning these values.”

Russian speakers generally are for small government and free enterprise, making them profoundly different from American progressive Jewry. What progressive and Russian Jews have in common is a lack of interest in religion and a propensity to intermarry. While progressives look for Jewish identity in secular universalism, the American Russian-speaking Jews still embrace the idea of Jewish unity and Zionism. Like previous American immigrant populations who have assimilated and had an outsized influence, many Russian Jews already contribute to contemporary American culture, education, and politics. They will profoundly affect the future course of the American Jewish Diaspora experience.

For American Jews who look at Israelis two-dimensionally, adding Russian Jews to the Israel mix should cause them to reevaluate some binary stereotypes of Israelis. The US Jewish Diaspora might be surprised that Russian Jews contribute so much to contemporary Israel’s rich mosaic and complexity. For progressives who demonize Israelis on the Right, understanding why secular, educated Ashkenazi Russian-speaking Jews lean to the Right would go a long way in painting a more realistic three-dimensional picture of Israeli politics, culture, technology, and tradition. They represent nearly 20% of Israeli Jews.

As Harriet Sherwood wrote in The Guardian, “They have influenced the culture, hi-tech industry, language, education and, perhaps most significantly, Israeli politics…. Some came to pursue the Zionist dream; some came to escape antisemitism, and a large number came for better economic prospects. They brought culture – art, theatre, music – and new entrepreneurialism.” And their children continue to reshape the Jewish state.

Researcher Lily Galili, writing for the Brookings Institute, said, “The over one million people who immigrated to Israel from the FSU in a wave from the beginning of the 1990s have changed Israel to its core — socially, politically, economically, and culturally. Within the first six years, they formed what became a large secular nationalist political camp that secures right-wing rule to this day.” They are on a collision course with “the unbridgeable gap between the Zionist secular Law of Return that allows all Jews to settle in Israel, and the rabbinical Orthodoxy in charge of their absorption, which defines hundreds of thousands of members of the Russian-speaking community as non-Jews under halachic law.”

This mass immigration has caused the Jewish state significant challenges and opportunities. According to Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, “As many as a quarter of them are not Jews according to religious law…. [yet have] infused the country with a fresh dose of Zionism.” An NPR article said, “They feel Jewish. They were raised Jewish. They have Jewish names. They once suffered for being Jewish in the Soviet Union. Now they suffer for being Russians in Israel.”

Prof. Benny Ish-Shalom, with former IDF chief of staff and defense minister Moshe Ya’alon, and Brig.-Gen. (res.) Elazar Stern, established the IDF’s Nativ center for identity and conversion for immigrant soldiers. So many of these young Israelis from the FSU who are not halachicly Jewish want to become fully Jewish and have already put their lives on the line to protect and build the Jewish state.

It is tragic and shortsighted that Israel has given the ultra-Orthodox control of conversions, a historical aberration, as conversion by Orthodox standards used to be more embracing and less rigid. Ironically, Russian-speaking non-Jew who puts his life in harm’s way to defend the Jewish state and wants to become Jewish, is thwarted by an ultra-Orthodox establishment that is, at best, non-Zionist, and rarely sends its children to the IDF.

As Amotz Asa-El writing in The Jerusalem Post said, “That’s not merely unfair; legally, morally and also religiously, this is what Moses meant when he rebuked the tribes of Reuben and Gad (Numbers 32:7): ‘Are your brothers to go to war while you stay here?’”

Grouping Russian speakers with all FSU Jews is a convenient shorthand. However, from 1970-1988, more immigrants from Ukraine arrived in Israel than from Russia. One just has to look at what is happening in Ukraine today to understand that Ukrainians and their diaspora are not keen to be defined as Russian. Overall, two million Jews and their relatives have emigrated from the FSU since 1970. Most of this mass emigration occurred since 1989 — about 1.7 million. About a third come from Russia, a third from Ukraine, and the rest are from the other Soviet republics.

Politically, the first generation of FSU immigrants found their political voice in Avigdor Liberman’s Yisrael Beytenu party. Secular and nationalistic, it advocated and still advocates for the particular needs of this community. Even as the second generation has come of age while joining other parties, they maintain their right-leaning outlook.

But despite being Israel’s most prominent Jewish minority, their political power has diminished by the second generation, gravitating to many other parties. When they voted as a bloc, Yisrael Beytenu received 15 Knesset seats at its peak and was the political kingmaker in Israeli coalition politics; but today, not so much.

Lahav Harkov, a senior contributing editor at The Jerusalem Post, wrote, “It seems that people abandoned Yisrael Beytenu because so many don’t feel like they need something special as Russian [speakers]…. The big Russian aliyah was more than 25 years ago already. Certainly, people born in Israel or who came as small children are very well integrated into society…. In the Israeli melting pot, Russian-speaking Israelis increasingly view themselves not as Russian-speaking immigrants but simply as Israelis.”

According to Prof. Ze’ev Khanin, a sociologist focusing on Russian-speaking Israelis at Ariel and Bar-Ilan universities, “In Israel, 30–50 percent of this group believe they should support Russian-speaking politicians. However, up to 70 percent do not.”

Russian Israeli Jewry has also been in the crosshairs of American presidents. In foreign policy, Bill Clinton said they were “an obstacle to peace with the Palestinians… among the hardest-core people against a division of the land. They’ve just got there, it’s their country, they’ve made a commitment to the future there. They can’t imagine any historical or other claims that would justify dividing it.”

As for FSU immigrants in the United States, Jonathan Sarna, the project head of Toward a Comprehensive Policy Planning for Russian-speaking Jews in North America, said that in New York City, one in five Jews lives in a Russian-speaking household, exceeding the Orthodox American Jewish population. Overall, there are probably around 750,000 Russian-speaking American Jews. The term “Russian-speaking Jews” encompasses the children of immigrants with distinctive cultural heritage. “Russian-speaking Jews, like so many Jewish (and Asian) immigrants before them in America, have exhorted their children to study hard and succeed. Stereotypically, they want them to attend the best schools, achieve the best grades, gain admission into the best colleges, and win the best jobs.“

Too many in the American Jewish Diaspora think they know Israel, viewing it through an Americanized perspective. They think they know what is best for Israelis, even if Israelis think differently and have to live with the consequences of their good intentions. Humbly, before giving too much advice, let’s truly understand Israel’s complexities before giving them “tough love,” which is rightly viewed as condescending.

Let’s begin by focusing on Israel’s most prominent Jewish minority population, who have much to say and contribute to the Jewish state’s security, culture, and unity.

Dr. Mandel is the Director of MEPIN (Middle East Political Information Network). He regularly briefs members of Congress and their foreign policy aides. He is the Senior Security Editor for the Jerusalem Report. He is a regular contributor to The Hill and the Jerusalem Post. He has been published in National Interest, Must Reads-Foundation for Democracies, RealClearWorld, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, National Cyber Security News, MSN, the Forward, JNS, i24, Rudow (Iraq), The NY Sun, Moment Magazine, The Times of Israel, Jewish Week, Kurdistan24, IsraelNationalNews, JTA, Algemeiner, WorldJewishNews, Israel Hayom, Thinc., Defense News, and other publications.

There was no “safety net” in the Soviet Union. Unless retired or disabled, one had to work. If one had a job where he did not have to do much he still had to show up. The governing principle was “whoever does not work, does not eat”. “Parasitism” was not tolerated. If one had no money to buy food then one would have to go and beg neighbors to loan him a few rubles until the next paycheck – and they usually would help. Economic security – yes, since everyone worked for the state then the state would provide a job. Not necessarily a job one would like though. For example, many refuseniks in the 80’s were members of the intelligentsia but they were fired from their jobs and had to do physical labor (a rail car loader/unloader or a construction worker, for example) in order to feed their families. Some of them went to Siberia or Central Asia to do contract work.

I played with a number of these older Russian Jews who left the FSU after 1990 as fellow musicians mostly for economic reasons but also on account of antisemitism and wanting their children and grandchildren to grow up free of that and listening to their stories was one of the things that changed my mind about the Soviet Union and Marxism about 25 years ago. Many of them lived in or near Far Rockaway and Coney Island. It debunked the notion that the CIA only allowed fascists over here. These people had not been anti-Soviet and missed the safety net and economic security from that time, despite the institutionalized antisemitism.

With the regard to the question of hegemony of a branch of the ultra-Orthodox over deciding who is a Jew, I’m reminded of Brecht’s satirical poem, “The Democratic Judge.”

https://abev.wordpress.com/2005/12/16/the-democratic-judge-a-new-translation/