The West is restoring the global strategic vision that gave it victory in the world wars and the Cold War.

A new Western global strategy is taking shape. Its development was evident during President Biden’s tour in the Middle East—specifically at the July 14 online summit with the quadrilateral I2U2 Group: Israel’s Prime Minister Yair Lapid and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi (the I’s) and the United Arab Emirates’ president Mohamed bin Zayed and Mr. Biden (the U’s).

I2U2 launched in October 2021 to promote cooperation on economic and technological issues. A joint declaration shortly before the July virtual summit promised “to harness the vibrancy of our societies and entrepreneurial spirit . . . with a particular focus on joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, health and food security.”

Yet geopolitics loom behind economics. Jake Sullivan, Mr. Biden’s national security adviser, compared I2U2 to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the embryonic Indo-Pacific alliance of the U.S., Japan, Australia and India. Indian and Emirati media routinely refer to I2U2 as the “Western Quad.” U.S., Indian and Emirati media all see it as an extension of the 2019 Abraham Accords, which outline both economic and military cooperation. Even in purely economic matters, the “security” angle is apparent: I2U2 repeatedly mentions “energy security” and “food security.”

The longer view is even more pertinent. Beyond I2U2, the Quad and the Abraham Accords, one must consider many analogous developments: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization re-energized by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and about to expand to include long-neutral Finland and Sweden; a semiformal Eastern Mediterranean security alliance bringing together France, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt; the Negev Summit architecture that provides for tight security cooperation between Morocco, Egypt, Israel, the U.A.E. and Bahrain; the reinvigoration of an Anglo-Pacific defense community Australia, the U.S. and the U.K., or Aukus; the upgrading of the U.S.-Taiwan relationship; the rise of Japanese and South Korean military efforts and cooperation despite an acrimonious history.

A U.S.-supported arc of strategic cooperation now stretches from Western to Eastern Eurasia, as a defensive oceanic “Rimland” against the hostile continental powers of Eurasia—China and Russia. Such an approach has a historical pedigree in the grand strategies of Halford John Mackinder (1861-1947) and Nicholas John Spykman (1893-1943), which underpinned British, American and global Western defense policies during World War I, World War II and the Cold War.

Mackinder, a British geographer, famously suggested in a 1904 paper, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” that world geopolitics was leading to a clash between continental empires based in Eurasia (which he called “the World-Island”) and maritime powers located in non-Eurasian islands, archipelagoes or smaller continents. He elaborated on these intuitions in his 1919 book, “Democratic Ideals and Reality.” Primarily concerned by the rise of Russia under the czars and then the Bolsheviks, he also pointed to a potential German-Russian condominium.

Spykman, a Dutch-born American professor of international relations at Yale, warned in the early 1940s against isolationism and then, after Pearl Harbor, against the long-term viability of the war alliance with the Soviet Union. His books, “America’s Strategy in World Politics” (1942) and “The Geography of the Peace” (1943), helped shape the Cold War doctrine of containment, which remained in force until 1989.

The difference between Mackinder and Spykman lies with the Rimland, the sea-accessible periphery of Eurasia. “Who rules the World Island rules the World,” Mackinder asserted. The strategic priority is thus to prevent the emergence of a single dominant power in continental Eurasia. Such a power, should it materialize, would be close to world domination, no matter what.

Spykman took the opposite view: “Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia.” Continental empires, including the Soviet Union or an alliance between Moscow and Beijing, can be checked by an American-controlled crescent spreading from the European coast (Western and Mediterranean Europe) through the Middle East (the Arab-Turkish-Persian world) to the monsoon lands (South and East Asia).

Spykman’s grand strategy proved highly effective, and highly compatible with such additional strategic dimensions as nuclear deterrence or access to oil, even if it was subject to revision time and again. It initially translated into four regional alliances, complemented by bilateral U.S. alliances or agreements with Spain, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Japan and South Korea.

Among the regional alliances, only NATO was so successful as to continue in operation and be enlarged after the Cold War’s denouement. The Central Treaty Organization—formed in 1955 by the U.K., Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Turkey—never took off. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization—also established in 1955, and including the U.S., U.K., Australia, France, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand—faltered in 1975. Anzus—the alliance between Australia, New Zealand and the U.S.—is technically still in force despite differences between Wellington and Washington, but it may be supplanted by Aukus.

In the Middle East, plans for a strong postwar Anglo-Arab or American-Arab partnership were thwarted by a succession of pro-Soviet Nasserist and Baathist revolutions from 1952 to 1970. Non-Arab and pro-Western Iran then succumbed to a fanatical anti-Western revolution in 1979. On the other hand, Israel, which American strategists originally saw as an encumbrance, was reappraised as a valuable strategic player after the 1956 and 1967 wars, and finally recognized as the most reliable regional ally. The apparently vulnerable conservative Arab regimes of Morocco, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Oman and the Gulf states endured as Western allies, and so did Egypt once it rejected the Soviet embrace under Anwar Sadat. A different but more reliable Middle Eastern Rimland took shape. Non-Arab, Europeanized and secularized Turkey, a member of both NATO and Cento, was an essential Rimland partner throughout the Cold War.

In the Far East, the initial Rimland strategy targeted a Soviet-Chinese communist empire that briefly existed until the Korean War but gave way in the 1960s to a fierce “communist civil war.” Unfortunately, the U.S. failed for too long to perceive the Soviet-Chinese rift’s implications and was accordingly drawn into the Vietnam quagmire. It took Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger to approach China and turn it into a partner, thus ending the Soviet bid to rule the “World Island.”

The emerging 21st-century Rimland strategy raises several questions. First, is the present continental Eurasian menace real? Yes, without a shadow of a doubt. China and Russia are both major military powers, nuclear and conventional. Both are authoritarian, hypernationalist, revisionist imperial states, bent on destroying the Western-centered world order. Both suppress domestic ethnic, religious and political dissent. Both are planning and training for regional confrontations with neighboring countries and ultimately a global confrontation with the West. Both have already engaged in unilateral military interventions abroad (including in the South China Sea, Syria and Ukraine). Both have heavily invested in soft power to anesthetize world opinion, in the tradition of Sun Tzu, the Okhrana and the KGB, and both largely succeeded until the past few years.

The 21st-century Beijing-Moscow axis has already proved more durable and internally reliable than its 20th-century forerunner. The two nations have closely cooperated over the past quarter-century, either within such partnerships as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or through bilateral agreements.

Even more worrisome is the present Eurasian axis’ power base. The Soviet-Chinese partnership in the 1950s could boast of its massive area (two thirds of the Eurasian landmass) and population (more than one billion, or 40% of the world) and its natural resources. But the Soviet economy and technology lagged behind the West’s in every field except weaponry and space. China was an underdeveloped country. Today, China is close to economic and technological parity with the global West (which includes Japan, South Korea and Taiwan) and could plausibly replace America as the world’s economic epicenter in a generation.

The second question is whether Mackinder’s and Spykman’s insistence on geographic constraints and Spykman’s more focused insistence on the Rimland are still valid in the age of planes, satellites and internet. The Chinese certainly think so, as evidenced by their Belt and Road Initiative, which would open up all of Eurasia to commercial and military circulation and bring the Eurasian coastlines into the sphere of the inland empires.

The third question is whether all potential Rimland partners fully agree on a coordinated containment strategy against China and Russia. That is so far unresolved. Europe may be more wary of Russia than of China, whereas the contrary might be true in South Asia and the Indo-Pacific region. Some Western strategists think it would be a Vietnam-style blunder not to attempt to decouple Russia, the weaker Eurasian partner, from China. And some countries that formally belong to the Rimland alliances are tempted to stay neutral in the new Cold War: Turkey, still a NATO member but also a nationalist-Islamist regime since 2002, joined a July 22 strategic Russia-Iran summit in Tehran intended as a response to Mr. Biden’s tour.

The fourth and final question is whether the new Rimland strategy is a conscious one. Did Western leaders decide at some point to revive Mackinder and Spykman, or is the present strategic turn a cumulative result of multiple ad hoc initiatives?

The available evidence—books, op-eds, reports—suggests that scholars have rediscovered the classic Anglo-American geopolitists since the early 2000s in the context of increasing Chinese and Russian aggressiveness but failed to elaborate it fully until recently. At the government level, the Trump administration laid the foundations of a new containment strategy once it overcame its early neo-isolationist temptation, and the Biden administration was wise enough to keep up the momentum. What is still lacking is the equivalent of George F. Kennan’s “Long Telegram” of 1946 and the Truman Doctrine of 1947, which turned Spykman’s insights into policies.

Mr. Gurfinkiel, a French author, is a fellow at the Middle East Forum and a contributing editor of the New York Sun.

It’s just a bridge over troubled water.

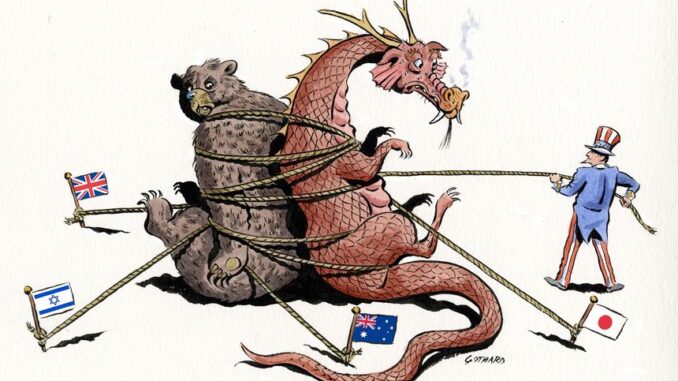

When you look at the cartoon used in this article, it describes everything that is wrong with the outlook of the author. The US is forcing the Russians and Chinese to act in concert against the West, even as the US is also working to undermine almost every aspect of Western strength and stability.

If there were a Chinese 5th Column in power in the US manipulating all the world to improve China’s position from every angle imaginable, it could not act with greater effect than the current US administration at achieving these ends. Silly me, did I say ‘if’?

Quite a moronic analysis by Gurfinkiel