In new book ‘Watching Darkness Fall,’ former US ambassador David McKean illustrates how antisemitism, apathy and internal politics set America back in the war against Germany

<

>

In 1938, William Dodd, the United States ambassador to Nazi Germany, publicly declared that Hitler wanted to kill all the Jews not just in Germany, but the entire European continent. Months later, the Kristallnacht pogroms indicated he was right.

Despite Dodd’s perception, the US diplomatic corps overlooked a number of totalitarian threats at the time, according to “Watching Darkness Fall: FDR, His Ambassadors, and the Rise of Adolf Hitler,” a new book by David McKean.

The author is himself a former US ambassador to Luxembourg under the Obama administration. The inspiration for the book came while McKean was serving there from 2016 to 2017.

Although a relatively small country, Luxembourg has the second-largest military cemetery in Europe after Normandy; those buried there include Gen. George S. Patton. McKean was struck by how powerful the memory of World War II remained in Luxembourg, which was overrun twice by Germany. He eventually decided to write a book focusing on four members of president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s diplomatic corps during the leadup to war.

“I just thought it was such a different way of looking at our foreign policy during this period,” McKean told The Times of Israel. “To learn how these ambassadors, who for the most part came from fairly similar backgrounds, turned out to be very, very different in their approach to the job… It is an incredibly interesting perspective on our diplomacy at the time.”

On the positive side, there were Dodd and the colorful William Bullitt — a millionaire and bon vivant who served as ambassador to the USSR and France. Bullitt helped get Sigmund Freud out of Austria after the Anschluss, and made a questionable return home once Paris fell.

As for the negatives, it’s a toss-up between two controversial figures. Joseph P. Kennedy, the patriarch of the future political dynasty, saw his tenure as ambassador to the UK end after defeatist comments to the press in 1940. Breckenridge Long was an ambassador to Italy who praised Benito Mussolini, then hindered Jewish refugees from reaching the US while serving as assistant secretary of state during WWII.

McKean said that Kennedy “was not cut out to be an ambassador,” and that Long “was just a terrible appointment.”

United States Ambassador William E. Dodd leaves the presidential palace in Berlin, September 6, 1933, after presenting his credentials to President Paul von Hindenburg. After receiving military honors, the new ambassador made a brief speech in which he mentioned the cultural ties between the two nations. (AP Photo)<

>

<

>

Contemporary reverberations

Lately, McKean has been thinking about the role of diplomacy during the current Russia-Ukraine crisis. He has high praise for the performance of Oksana Markarova, the Ukrainian ambassador to the US, who was a guest at President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address on March 1.

“Not only has she [been] able to talk directly with members of Congress and officials in the White House, she has made the case — very effectively — to the American people, that Ukraine needs more US military aid and tougher sanctions on Russia,” McKean continued.“Ambassadors can often play a critical role in conveying information both to and from their home country,” McKean said in a follow-up email. “For example, for millions of [Americans] who saw her at the State of the Union and have seen her on news shows, Ukraine’s ambassador to the United States, Oksana Markarova, has become an important voice for Ukraine in its fight against Russian aggression.”

The former diplomat pointed out that just as Roosevelt relied on his ambassadors in Europe to be his eyes and ears on the ground in the years leading up to WWII, so, too, ambassadors around the world often play that role today.

Behind every great man…

When Roosevelt first took office in 1933, he had limited foreign-policy interests – while the public had significant isolationist tendencies, a legacy of WWI. McKean also noted sizable hostility toward immigration among Americans of the day.

“It was not an issue the American people accepted as something we should take interest in,” said McKean. “Waves of European immigrants were never a popular issue. The United States, frankly, was also quite an antisemitic country at the time.”

However, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt overruled Long when it came to saving the mostly Jewish passengers on the refugee ship SS Quanza in 1940.

“She was clearly a great humanitarian and in many ways Franklin’s political conscience,” McKean said.

In one chapter of the book, the Roosevelts are having breakfast, each reading the morning paper. When the first lady learns that Long is impeding immigration, she becomes furious: “Franklin, you know he’s a fascist!”

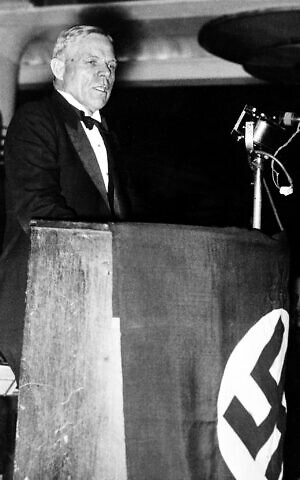

Dr. William E. Dodd, United States Ambassador to Germany, speaks at the Festival for International Exchange of Pupil at a Berlin concert hall May 29, 1935. (AP Photo)<

>

<

>

“She was a truth-teller,” McKean reflects, “with a very honest humanitarian streak.”

McKean cited similar reasons for his admiration of Dodd, calling him “sort of the unwavering moral compass… I think he told Roosevelt the truth.”

As the book explains, Dodd was hardly philo-Semitic when he took up his ambassadorship in 1933. Although he rented two floors of a posh Berlin residence from a wealthy Jewish businessman and his family who lived on the third floor, he failed to recognize their motivations in renting it out to him.

“Dodd was so happy to get the apartment at a good rate that he did not recognize that the family living on the third floor did this hoping for American protection,” McKean said.

However, following his first meeting with Hitler, Dodd saw the Nazis as they really were. “They were evil, to put it simply,” McKean said.

Unheeded warnings

As Dodd kept interactions with the Reich to a minimum, his warnings went largely unheeded in Washington.

‘)<

>

<

>

“[Some] of the things he was concerned with — such as the length of cables sent to Washington, and the wealthy lifestyles of other diplomats — meant that he managed to not be taken seriously by a number of people in the Department of State,” McKean said. “In particular the secretary [of state] at the time, Cordell Hull did not consider him an able diplomat… I fault [Dodd] a little bit. I think he was somewhat naive.”

In contrast, there was the worldly Bullitt, the so-called “Champagne ambassador” known for his romances and the extravagant parties he held in Paris. The book describes him as ambitiously angling for higher positions. In 1937, he briefly left Paris on his own initiative to go to Berlin and meet with high-ranking Nazis in the twilight of Dodd’s tenure there. After conferring with Hermann Goering, Bullitt wrote a private letter to FDR noting the Reichsmarschall’s distaste for Dodd, which he said was widespread in Germany. He shared a scathing take on Goering: “as you know, he strongly resembles the hind end on an elephant.”

As Dodd’s ambassadorship came to an end, Kennedy’s began at the Court of St. James’s. The latter questioned whether FDR wanted to appoint an Irish-American to this post, but the president backed him.

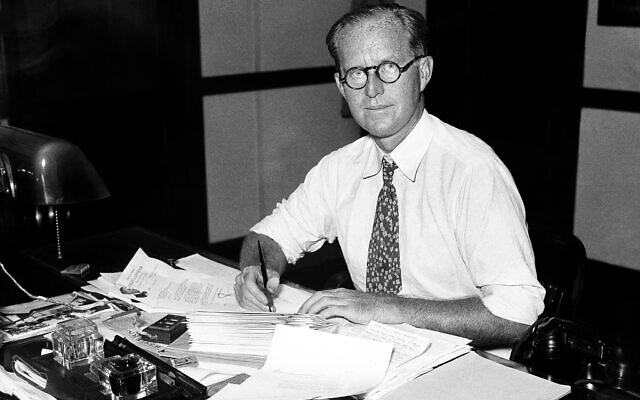

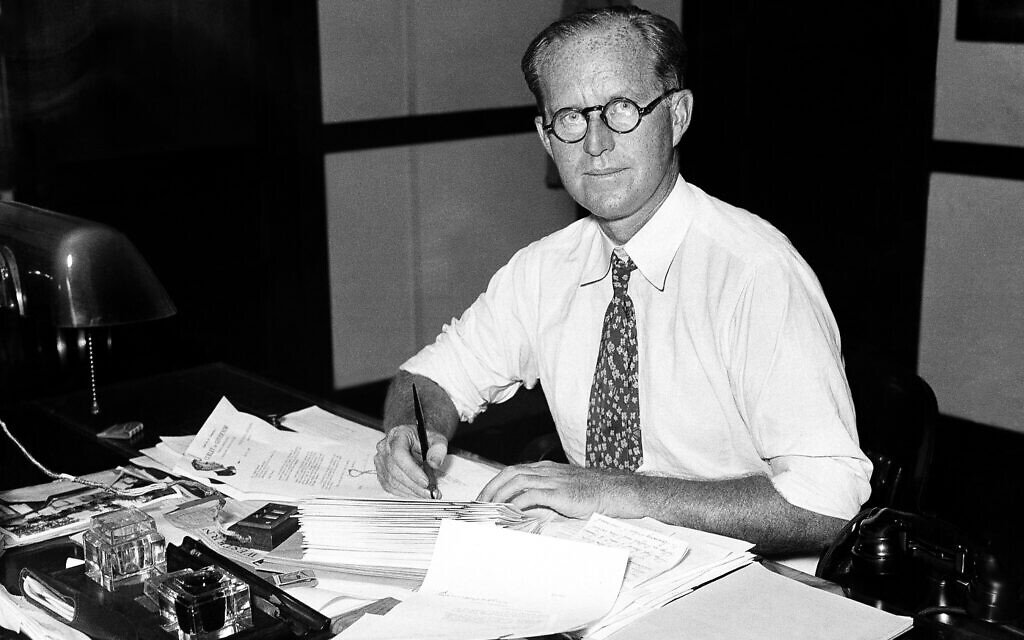

Joseph P. Kennedy, then chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission is shown at work in his shirt sleeves during Washington’s heat wave on July 16, 1934. (AP Photo)<

>

<

>

“[Roosevelt] felt Joe Kennedy had done a good job at the Securities and Exchange Commission, and actually a very good job as head of the Merchant Marine,” said McKean, who in addition to his longtime work in government is also the former head of the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum in Boston, named after the former ambassador’s son, the future US president.

FDR nominated the elder Kennedy in 1938 for reasons beyond his past performance in office. A presidential election was on the horizon, and an ambassadorship would sideline this political rival.

“It was good to have [Kennedy] out of the country in 1940, an election year,” McKean noted. “[FDR] did not want Kennedy — who was very influential, particularly with the Catholic vote, and an enormously wealthy individual — he did not want him around.”

The book chronicles Kennedy’s missteps as ambassador. (There’s also a head-shaking account of an incident several years earlier, in 1934, when his teenage son Joseph Jr. visited Nazi Germany and wrote letters defending, at times, the Reich’s antisemitism and sterilization policies.) Fatefully, the elder Kennedy supported British prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler at Munich.

In this Jan. 5, 1938 file photo, Joseph P. Kennedy, left, US Ambassador to Great Britain, stands with his son, future president John F. Kennedy, in New York. (AP Photo, File)<

>

<

>

“I think there were several big turning points in that period,” McKean said. “[Munich] was very much a turning point for Roosevelt… Hitler was someone who lied constantly. He clearly had a plan to dominate Europe and was willing to do whatever necessary to achieve that objective.”

Even after Munich, Kennedy continued to defend Chamberlain while disparaging his eventual successor, Winston Churchill.

“[Kennedy’s] view of the war in Europe, in the end, did not concur with Roosevelt’s at all,” McKean said. “He just did not have a successful tenure as ambassador because he was ultimately a defeatist.”

The book ends dramatically for its subjects. Dodd suffered the loss of his wife in 1938. His own health declined after he was compelled to step down as ambassador; he died in early 1940. That year, Kennedy and Bullitt each experienced WWII directly — Kennedy during the Blitz, including a raid that allegedly targeted him; and Bullitt during the Fall of France, when an unexploded bomb momentarily blinded him. After the Germans captured Paris, Bullitt was credited with helping prevent its destruction.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy, known as Joe Kennedy, the American Ambassador in London smiling as he leaves the House of Commons, London on August 29, 1939, after being present at the special sitting of the house. (AP Photo/Staff/Len Puttnam)<

>

<

>

Indiscretion, that downfall of diplomats, doomed both Kennedy and Bullitt. After Kennedy made pessimistic remarks about Allied prospects in WWII, he resigned as ambassador. Bullitt disobeyed the administration’s order to go to Vichy, where the new, collaborationist regime was coalescing, and instead made a return home that was daring but led to a falling-out with FDR. Meanwhile, Long used his political savvy to ingratiate himself with both FDR and Secretary Hull, with a tragic result: He kept tens of thousands of Jews, by the book’s estimate, from escaping to the US.

If the ambassadors did not collectively reflect FDR’s growing desire to challenge the Axis, they nonetheless represented a key element of American popular opinion.

“Obviously, we live in an America that now has 20-20 hindsight into the 1930s,” McKean said. “Most of the American people [at the time] felt there were two great oceans that separated us from other nations around the world. There were none of the common international institutions you have now. [The US was] quite isolationist. The American people wanted to keep it that way.”

<

>

<

>

I believe that it was becuae of inbred Anti0Semitism , especially amongst ther Politicians who ran the country, the Administration etc. Even though there were Jews in it, they were totally assimilated and just JINOS.

So there was also resistance from the wealthy, long established JEWISH “cultured” opera going sector of German Jews, who regarded hordes of bearded, Yiddish speaking Jews are a different species, and not really human. They bear a lot of the guilt also.

But Administration.Anti-Semitism was the major cause, My opinion, backed by the story of the SS St. Louis . Canada was just the same.