In repeatedly breaking his most solemn promises to coalition partners, Netanyahu has convinced growing ranks of potential allies it’s simply not profitable to do business with him

By HAVIV RETTIG GUR, TOI Today, 6:02 am

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks at a ceremony honoring medical workers and hospitals for their fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, in Jerusalem on June 6, 2021. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett may have accomplished the seemingly impossible. Sunday will mark not only the end of 12 consecutive years of Benjamin Netanyahu’s premiership but, if all goes to plan, the founding of the strangest and most improbable government in the history of the country.

Islamist Ra’am and hawkish New Hope, progressive Meretz and deeply conservative Yamina, parties avowedly religious and passionately secular, MKs anxious to see the establishment of a Palestinian state and MKs equally anxious to avoid that outcome, are all jostling for space at the coalition table.

Many have already noted that the glue that holds that fractious new coalition together is none other than the man they seek to replace — a feat for which, as one comedian quipped, “he deserves the Nobel peace prize.”

But just what is it about Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that actually keeps all those disparate parties united in their commitment to depose him?

Is it, as Likud leaders have complained, “wild hatred of Netanyahu?”

Israelis protest against the unity government outside the home of Yamina MK Nir Orbach in Petah Tikva on June 8, 2021. (Avshalom Sassoni/Flash90)

Some of the right-wingers working to boot Netanyahu from power surely hate him. For Avigdor Liberman of Yisrael Beytenu, Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked of Yamina, and Gideon Sa’ar of New Hope, who all once worked directly for him as political aides and appointees, a lot of the animus is personal, and in no small part caused by Netanyahu himself.

But what of the rest? What of New Hope’s Sharren Haskel, Yifat Shasha-Biton and Ze’ev Elkin, or Yamina’s Nir Orbach, Abir Kara and Idit Silman? Netanyahu needed just two defectors, potentially even one, to prevent Sunday’s expected ouster — and insisted repeatedly for the past two weeks that he’s already got more than two rebels. But as of this writing, they haven’t materialized. Why? Why couldn’t he coax them away even with the offer of slots on the Likud slate or attractive cabinet posts?

Some in the new coalition, on the center-left, disagree with Netanyahu on substance, on the economy or the Palestinians. But many others, from Yisrael Beytenu to Yamina to New Hope, do not fundamentally disagree with him on any issue. Yet they refuse to do business with him even in the service of causes they all share.

The simplest explanation for Netanyahu’s downfall, the simplest catalyst of the unlikely new alliance that has emerged to oppose him, is Netanyahu himself. Or more precisely, the way Netanyahu’s past behavior and treatment of political rivals and allies alike have robbed him of the capacity to negotiate and maneuver.

Israelis protest against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu outside the prime minister’s official residence in Jerusalem on June 5, 2021. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Broken promises

It is important to grasp the scale of distrust that Netanyahu elicits in the political system, not only in the “change bloc” but even in his own Likud front bench. It’s a distrust Netanyahu has earned.

We can start the story of Netanyahu’s present predicament in October 2012, when the Likud leader announced a union of Likud’s and Yisrael Beytenu’s election slates, a union that Yisrael Beytenu’s leader Liberman, a former Likudnik, hoped would mark his long-delayed return to the ruling party. The two parties ran together in the 2013 election, but Netanyahu spent the ensuing year working hard to stymie Liberman’s efforts to merge them, and an embittered Liberman broke the alliance in 2014 and refused to join Netanyahu’s coalition after the 2015 election.

Netanyahu finally convinced Liberman to let bygones be bygones in 2016, appointing him defense minister in order to draw him into his coalition. But as with the party merger tease two years earlier, Netanyahu then gutted Liberman’s post of any significant power, communicated with the military over the new minister’s head, and caused a humiliated and frustrated Liberman to resign in 2018 without a single meaningful ministerial decision to his name.

Yisrael Beytenu party chairman Avigdor Liberman arrives at a faction meeting in the Knesset in Jerusalem on May 31, 2021. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

The point here isn’t to sympathize with Liberman’s plight, but to shed light on Liberman’s calculations when, in the wake of the April 2019 race, he saw a chance to return the favor — and took it. For seven long weeks of coalition negotiations, he let Netanyahu believe he would eventually join his coalition, right up until May 30, the final day of Netanyahu’s mandate from the president. It was only then, hours before Netanyahu’s deadline for forming a government, that it became clear that Liberman would not join the Netanyahu coalition, and the country’s two-year, four-election crisis began.

Liberman wasn’t driven by a mere desire for revenge. He’s a savvy politician who has shown repeatedly that he is able to rise above personal enmity for the sake of high political office. It was simply that Netanyahu had repeatedly proven that no promise one extracted and no appointment one won from him at the negotiating table was safe when the time came to cash it in.

Instead of the introspection one might expect after such a setback, Netanyahu has spent the past two years doubling down on similar maneuvers.

He thought he had finally won his way out of the impasse after the March 2020 race when he signed a power-sharing deal with Benny Gantz, a move that shattered the Blue and White alliance and left him in power for another 18 months at least via a rotation deal.

Defense Minister Benny Gantz, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and, behind them, Shin Bet chief Nadav Argaman, at a press conference after the Gaza ceasefire, Tel Aviv, May 21, 2021. (Amos Ben Gershom/GPO)

New institutions were forged in that coalition agreement and strange new concepts were introduced into Israel’s constitutional Basic Laws, including the “alternate prime minister,” the “parity government,” a premier who no longer has the power to fire ministers in his own cabinet, a stipulation that any vote of no confidence by one side would automatically hand over the premiership to the other — all to satisfy a wary Gantz that wily old Netanyahu would keep true to his word with, as Netanyahu himself had put it, “no tricks and no shticks.”

But the tricks and shticks came fast and furious as soon as the ink was dry. Netanyahu immediately set about undermining the deal via various actions, chief among them the unprecedented step of refusing to pass a state budget for the 2020 fiscal year — thereby forcing a snap election in March of this year, before Gantz could take his seat as prime minister.

This time, Netanyahu had every reason to believe he had beaten the odds. By early 2021 he could boast a world-leading vaccine drive and four peace agreements, while facing a splintered opposition and expecting a dramatic downturn in Arab turnout. Then came election day, and it confirmed yet again the same deadlock that had plagued the country for three previous votes.

The new government is not a sudden pivot for Israeli politics, but simply the latest step in a piecemeal expansion of the circle of distrust Netanyahu has steadily built around himself. The crisis that began in April 2019 was caused by Netanyahu’s careless (and, it must be said, largely unnecessary) alienation of a key ally. The new government expected to be sworn in on Sunday comes because he has since managed to alienate (once again, largely unnecessarily) additional former allies he could not afford to lose.

Israelis protest against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu outside the prime minister’s official residence in Jerusalem on June 5, 2021. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

And he did it in exactly the same way: by breaking so many coalition promises so consistently that he lost the capacity to promise and negotiate.

The best evidence for that failure is the startling fact that Likud’s persistent promises of generous appointments have failed to tempt to Netanyahu’s banner even the most junior and uncommitted of “change bloc” MKs.

Is this the first cohort of lawmakers in Israel’s history in which not one defector can be found? Or, more likely, is a promise from Netanyahu no longer reliable enough to cause anyone to switch sides?

(There was one party defector: Amichai Chikli. But he framed his abandonment of Yamina as a principled stand and has not asked for, nor received, any guarantees from Likud for the move. He has since talked of forming a new party.)

The Sa’ar maneuver

Gideon Sa’ar, head of the New Hope party, speaks at a conference in Jerusalem on March 7, 2021. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Over the past week, it became clear that even his looming ouster from power hadn’t led Netanyahu to reexamine the pitfalls of mistreating allies and reneging on solemn commitments.

He has spent the past two weeks attempting to draw Gideon Sa’ar’s New Hope and Mansour Abbas’s Ra’am away from the Lapid-Bennett alliance. He has failed.

In a phone call between Netanyahu and Sa’ar on May 29, Netanyahu asked Sa’ar to meet with him to discuss a rotation offer in which he would step aside and Sa’ar would have first go as prime minister.

Sa’ar refused on the spot, on the assumption that the offer wasn’t in earnest, but was a ploy to sow distrust in the Bennett-Lapid coalition.

Netanyahu has leaked word of new offers to Sa’ar repeatedly in the week since that refusal — but no one believes him.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the Knesset on July 29, 2013. Naftali Bennett (left) and Gideon Sa’ar are seated in the foreground. (Miriam Alster/Flash90)

As Naftali Bennett explained publicly on May 30 about the first offer, there was a simple reason that Netanyahu kept failing: “There was yet another attempt, a public one, to establish a [right-wing] government, with Gideon Sa’ar first in rotation and Netanyahu second. I, of course, agreed. But the attempt failed because no one believes those promises will be fulfilled.”

The Abbas rejection

Then came Mansour Abbas’s turn. Netanyahu has called Abbas dozens of times in recent weeks, including repeatedly over the past few days.

According to a Channel 12 report on Sunday about one such call from last week, apparently leaked by Ra’am officials, Netanyahu has been trying to convince Abbas that he can deliver for Israel’s Arab community where Lapid and Bennett can not.

Ra’am leader Mansour Abbas speaks to the Kan public broadcaster during an interview from his home in the northern town of Maghar on June 3, 2021. (Screen capture: YouTube)

“I’m the only one who can lead this, all their promises are written on ice,” Netanyahu reportedly told Abbas in the call, using a Hebrew expression meaning that Abbas’s coalition agreement with Lapid and Bennett won’t be honored.

Continued Netanyahu: “I believe in change, I want to do this together with you. I’m the only one who can open a new page with the Arab community. My stature and the fact that my government will be a right-wing government will allow me to do things they won’t be able to permit themselves to do.”

In a June 3 interview with Kan news, Abbas explained why he turned Netanyahu down.

“In the end, I reached the moment of decision and you ask yourself if you believe that the other side will actually carry out [their commitments], if there’s goodwill or not, because you can write any old thing down on the page,” he said.

Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid (L), Yamina leader Naftali Bennett (C) and Ra’am leader Mansour Abbas sign a coalition agreement on June 2, 2021 (Courtesy of Ra’am)

While “we didn’t get everything we wanted” with Lapid and Bennett, he said, he believes that what his party did win at the negotiating table it will actually receive when the time comes.

Promises promises

For Netanyahu, it’s the same story repeated time and again. On June 6, for example, Kan reported that Netanyahu called Shmulik Silman, husband of Yamina MK Idit Silman, for “a long conversation” that included (according to Kan) the suggestion that he, the husband, would be appointed to a senior post in a government company if Likud remained in power; if he could only convince his wife to change her vote.

Likud spokespeople denied knowledge of the call, but in Yamina people believe it’s true. It’s the kind of ceaseless wheeling and dealing that once earned Netanyahu a reputation as a wily and aggressive politician, but which has now passed the tipping point into mere trickery. The offers flow like water — and that’s precisely why there are no longer any takers.

Idit Silman takes part in a tree-planting event for the Jewish holiday of Tu Bishvat, in Beit El on February 10, 2020. (Sraya Diamant/Flash90)

Dishonesty is, of course, inherent in politics, and both Lapid and Bennett are violating oft-repeated election promises by the mere act of forming their new coalition.

Lapid has spent a year railing against the three-dozen ministers of the “bloated” Netanyahu government; his new one will have nearly the same number. Challenged by a reporter this week to defend the bloat, he said simply, “I can’t.”

Bennett is no better. In the week before election day, Bennett promised on live television never to sit with Lapid in a rotation deal. Challenged on that promise in an interview earlier this week, he could only explain that he’d prioritized another promise — not to allow a fifth snap election in a row — over the promise about Lapid.

Yet that’s not the sort of dishonesty that may have now ruined Netanyahu. He is certainly guilty of unfulfilled campaign promises, but they never interrupted his rise to power.

In his first campaign in 1996, Netanyahu vowed never to negotiate with Yasser Arafat — and then went on to sign the last agreement to be concluded between Israelis and Palestinians, the 1998 Wye deal, with that same Arafat. In the 2009 campaign, Netanyahu vowed to topple the Hamas government in Gaza, then spent the next 12 years helping to prop up that government in exchange for relative stability on the southern border.

Unfulfilled promises to voters aren’t an aberration, they’re a key feature of parliamentary democracy — as old as the institution of the elected parliament itself.

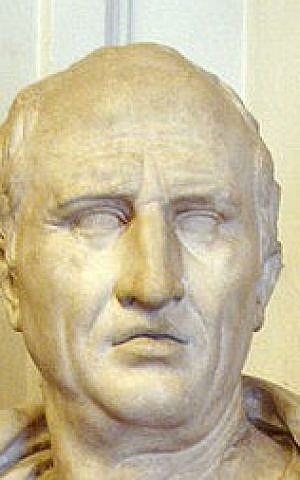

Bust of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Capitoline Museums, Rome. (Jack Ingram/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY)

Older, in fact. In 64 BCE, the famed Roman politician, orator and writer Cicero was standing for election as consul, the highest office in the republic. Ahead of the race, his brother Quintus wrote him a letter of advice on electioneering that remains startlingly relevant two millennia later.

“If a politician made only promises he was sure he could keep, he wouldn’t have many friends,” wrote Quintus. “It is better to have a few people in the Forum disappointed when you let them down than have a mob outside your home when you refuse to promise them what they want.”

Broken campaign promises aren’t even necessarily a sign of dishonesty. Bennett would presumably like to have kept those promises to voters, as Lapid and Netanyahu would like to have kept theirs. In parliamentary systems or complex geopolitical environments, that’s not always possible, so politicians from time out of mind have kept what promises they believed they could and didn’t worry too much about those they couldn’t (or didn’t want to).

Netanyahu’s dishonesty is different. He has broken promises not to voters, but to coalition partners, including those made in solemn written contracts, including even those that saw Basic Laws amended to ensure they were kept. In doing so, Netanyahu has cut the ground out from under the negotiations process itself. He has made it unprofitable to do business with him.

Many in the new coalition have deep qualms about their new partners, and many “change bloc” MKs are not personally opposed to Netanyahu or Likud. No monochromatic psychologizing about “wild hatred” is enough to explain the strange loyalty gripping the anti-Netanyahu camp.

The truth is simpler: Bennett is immune to Netanyahu’s threats to destroy him electorally because he’s certain Netanyahu will try to destroy him regardless of his actions. Sa’ar is immune to Netanyahu’s offers of the premiership because he believes he’ll be treated, at best, as Netanyahu treated Liberman. And so it goes down the slate, all the way to the last backbenchers.

1 Comment / 1 Comment