By Bethany Blankley | The Center Square

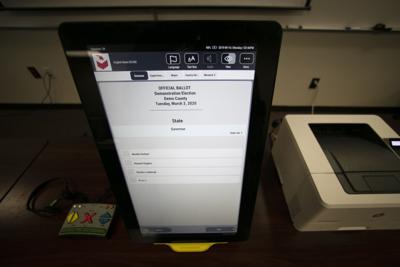

A sample ballot is shown using the Dominion Voting system Georgia will use Monday, Sept. 16, 2019, in Atlanta, Ga.John Bazemore / AP

(The Center Square) – The Dominion Voting Systems, which has been used in multiple states where fraud has been alleged in the 2020 U.S. Election, was rejected three times by data communications experts from the Texas Secretary of State and Attorney General’s Office for failing to meet basic security standards.

Unlike Texas, other states certified the use of the system, including Pennsylvania, where voter fraud has been alleged on multiple counts this week.

The Dominion system was implemented in North Carolina and Nevada, where election results are being challenged, and in Georgia and Michigan, where a “glitch” that occurred reversed thousands of votes for Republican President Donald Trump to Democrat Joe Biden.

While Biden declared victory Saturday in his U.S. presidential race against Trump, the Trump campaign is launching several challenges to vote counts in states across the country, alleging fraud.

Dominion’s Democracy Suite system was chosen for statewide implementation in New Mexico in 2013, the first year it was rejected by the state of Texas.

Louisiana modernized its mail ballot system by implementing Dominion’s ImageCast Central software statewide; Clark County, Nevada, implemented the same system in 2017. Roughly 52 counties in New York, 65 counties in Michigan and the entire state of Colorado and New Mexico use Dominion systems.

According to a Penn Wharton study, “The Business of Voting,” Dominion Voting Systems reached approximately 71 million voters in 1,635 jurisdictions in the U.S. in 2016.

Dominion “got into trouble” with several subsidiaries it used over alleged cases of fraud. One subsidiary is Smartmatic, a company “that has played a significant role in the U.S. market over the last decade,” according to a report published by UK-based AccessWire.

Litigation over Smartmatic “glitches” alleges they impacted the 2010 and 2013 mid-term elections in the Philippines, raising questions of cheating and fraud. An independent review of the source codes used in the machines found multiple problems, which concluded, “The software inventory provided by Smartmatic is inadequate, … which brings into question the software credibility,” ABS-CBN reported.

Smartmatic’s chairman is a member of the British House of Lords, Mark Malloch Brown, a former vice-chairman of George Soros’ Investment Funds, former vice-president at the World Bank, lead international partner at Sawyer Miller, a political consulting firm, and former vice-chair of the World Economic Forum who “remains deeply involved in international affairs.” The company’s reported globalist ties have caused members of the media and government officials to raise questions about its involvement in the U.S. electoral process.

In January, U.S. lawmakers expressed concern about foreign involvement through these companies’ creation and oversight of U.S. election equipment. Top executives from the three major companies were grilled by both Democratic and Republican members of the U.S. House Committee on House Administration about the integrity of their systems.

Also in January, election integrity activists expressed concern “about what is known as supply-chain security, the tampering of election equipment during manufacturing,” the Associated Press reported. “A document submitted to North Carolina elections officials by ES&S last year shows, for example, that it has manufacturing operations in the Philippines.”

All three companies “have faced criticism over a lack of transparency and reluctance to open up their proprietary systems to outside testing,” the Associated Press reported. In 2019, the AP found that these companies “had long skimped on security in favor of convenience and operated under a shroud of financial and operational secrecy despite their critical role in elections.”

In its third examination of Dominion systems in 2019, Texas officials once again rejected using it after identifying “multiple hardware and software issues that preclude the Office of the Texas Secretary of State from determining that the Democracy Suite 5.5-A system satisfies each of the voting-system requirements set forth in the Texas Election Code.”

The examiners raised specific concerns about whether the system “was suitable for its intended purpose; operates efficiently and accurately; and is safe from fraudulent or unauthorized manipulation.”

They concluded that Dominion systems and corresponding hardware devices did not meet Texas Election Code certification standards.

Last December, a group of Democratic politicians sent a letter to leaders of private equity firms that own the major election vendors asking them to disclose information including ownership, finances and research investments.

“The voting machine lobby, led by the biggest company, ES&S, believes they are above the law,” Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., a member of the Intelligence Committee and co-signer of the letter, said. “They have not had anybody hold them accountable even on the most basic matters.”

ES&S Chief Executive Tom Burt dismissed the criticism, telling NBC News that it was “inevitable and impossible to answer,” and called on Congress to implement “greater oversight of the national election process.”

“There are going to be people who have opinions from now until eternity about the security of the equipment, the bias of those companies who are producing the equipment, the bias of the election administrators who are conducting the election,” Burt told NBC News.

“What the American people need is a system that can be audited, and then those audits have to happen and be demonstrated to the American public,” Burt said.

Burt argued last year in an op-ed published by Roll Call that national regulatory oversight was needed, including requirements for paper backups of individual votes, mandatory post-election audits and additional resources for the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

NBC News examined publicly available online shipping records for ES&S and found that many parts for U.S. election machines, including electronics and tablets, were made in China and the Philippines. When it raised concerns about the potential for technology theft or sabotage, Burt said the overseas facilities were “very secure” and the final assembly of machines occurs in the U.S.

The AP also surveyed the election software being used by all 50 states, the District of Columbia and territories. Roughly 10,000 election jurisdictions nationwide were using Windows 7 or an older operating system in 2019 to create ballots, program voting machines, tally votes and report counts, the AP found. Windows 7 reached the end of its operational life in January 2020.

After Jan. 14, Microsoft stopped providing technical support and producing “patches” to fix software vulnerabilities, making Windows 7 easy to hack unless U.S. jurisdictions paid a fee to receive security updates through 2023, the AP found.

According to its assessment, multiple states were affected by the end of Windows 7 support, including Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, North Carolina, many counties in Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Computer professionals who advocate in favor these machines and their trustworthiness are exceptionally hard to find, except for some employees of the voting machine companies.

The years in “Raised concerns for years” means more than 30 years, See Counting Votes from the New Yorker in 1988.