587 exits worth $70b

Deals have gotten bigger as founders seek to grow firms, develop world-changing technologies, do good.

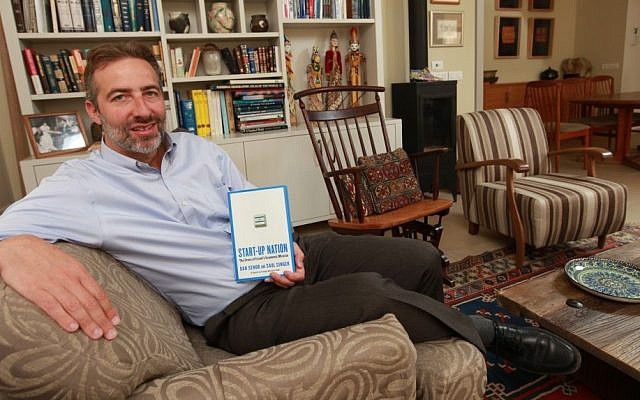

Tech has ‘strengthened in pretty much every metric,’ says author Saul Singer

The last 10 years have seen the so-called Startup Nation flourishing, with increasing numbers of multinationals taking notice, snapping up Israeli companies and technologies and setting up local R&D centers.

Startup entrepreneurs, once eager to sell their firms to the highest bidder as soon as they could, are now holding out longer and raising more money from venture capital or private equity funds to grow their companies on their own.

A look at the figures shows that in the past decade, Israel saw 587 exit deals — defined as initial public offerings of shares, or merger and acquisitions of Israeli startups — for a total of $70 billion, according to data compiled by PwC Israel. The deal of the decade was the acquisition by US tech giant Intel Corp. of Israel’s Mobileye, a Jerusalem-based maker of self-driving technologies, for a whopping $15.3 billion.

The past decade has also seen entrepreneurs who sold their businesses come back to the tech arena to set up other companies, this time equipped with more daring, skills and experience, and train a fresh generation of tech entrepreneurs.

“Startup Nation has grown stronger and bigger and deeper, and it has strengthened in pretty much every metric, whether it is number of startups or the amount of VC funding raised,” said Saul Singer in a phone interview with The Times of Israel.

Singer, together with Dan Senor, was the author of the book “Start-Up Nation,” which gave Israel the nickname and to a large extent defined the decade that followed its publication in 2009.

Over the course of that decade, Singer said, Israel’s tech ecosystem “has matured. We have more serial entrepreneurs, more people who have started multiple companies, have had some failures and some successes, and are now building companies that have a better chance at success.”

“Also, a lot of entrepreneurs want to do something that they believe is meaningful for the world, something that they feel will change things, so they are ambitious not just in terms of financial success but also impact on the world.”

There are more than 6,400 startups operating in Israel today, according to Start-Up Nation Central, which tracks the industry.

These entrepreneurs are dreaming bigger dreams and striving to create bigger companies. Whereas once you had to set up shop in Silicon Valley to raise $50 million from investors, today entrepreneurs are raising increasingly large amounts in Israel from foreign VC funds and multinationals that are constantly scouting for opportunities. And whereas once deals were made for thousands or millions of dollars, today’s deals and company valuations are reaching the multi-billion-dollar mark.

According to a list compiled by Techcrunch, as of December 2019, out of over 500 unicorns in existence — defined as privately held tech companies estimated to have a valuation of over $1 billion — 30 were founded by Israelis.

In 2019, the total value of exits reached $9.9 billion in 80 deals at an average deal size of $124 million. This compares to exits of $1.2 billion in 2010 in 23 deals at an average deal size of $51 million, according to data compiled by PwC Israel. The decade also saw the record year for exits — 2014, with $14.9 billion worth of exit deals, followed by 2015, which saw almost $11 billion worth of exits.

Delegations of company representatives and foreign government officials have been visiting Israel in what the founder and CEO of VC firm OurCrowd Jon Medved calls a new kind of “pilgrimage” to the Holy Land to study Israel’s tech ecosystem and see how they can copy the formula.

Other foreign firms are setting up shop locally. There are some 362 multinational corporations active in Israel, with Intel Corp. being the most active foreign firm in the period between 2014 and 2019, taking part in 52 corporate VC investment deals.

The US tech giant also acquired five companies for a total of $17.5 billion in the 2014-2019 period, according to a report by IVC Research Center, GKH Law Offices and Israel Advanced Technology Industries (IATI), an umbrella organization for tech firms operating in Israel. Google and Microsoft have also been very active in the past five years, acquiring 10 and eight firms, respectively.

Universities are hopping on the bandwagon too, offering entrepreneurship courses in a nod to the needs of Startup Nation.

Keeping it Israeli

The past few years have also seen a trend of some Israeli startups bought by multinationals that, rather than be swallowed and disappearing within the larger corporation, continue as a separate unit operating quasi-independently in a bid to preserve their identity, resourcefulness and agility.

Mobileye, for example, the maker of self-driving technologies acquired by Intel Corp. in 2017, has maintained its identity within Intel, becoming Intel’s center for developing assisted driving and self-driving technologies. Similarly, US chip maker Nvidia, which entered a deal to buy Yokne’am, Israel-based Mellanox Technologies Ltd. in March for a whopping $6.9 billion (completion of the deal is still pending final approval), said Mellanox will remain independent. Similarly, Habana Labs, snapped up by Intel for $2 billion in December, will continue to operate independently.

Looking ahead, the expansion seems set to continue, with Israel positioning itself as a leader in a number of growing fields: cybersecurity, as the threat of hackers grows globally; self-driving and autonomous cars, as traffic jams and pollution become key challenges; health technologies — where technology and healthcare meet, leading to more precise medications and better diagnostic and monitoring tools; food technologies, as the world seeks healthier and more environmental alternatives; agricultural technologies; artificial intelligence and internet of things technologies, which are already pervading all sectors of our lives.

Israeli skills are “pretty much exactly suited” to developments on the ground, said Singer. Artificial intelligence is being “added to everything,” and big data, algorithms, machine learning and computer vision are key to future technologies. Israelis are “very good at this,” he said.

So even as other nations are setting up their own successful tech ecosystems — including China and the UK, along with various US cities — “Israel is going to be no less prominent” going forward, Singer said.

Labor shortage

And yet challenges remain, the biggest one being a lack of skilled employees that could slow down the nation’s chugging tech engine. Israel suffers from a shortfall of some 15,000 skilled workers a year, according to Start-Up Nation central, which tracks the industry.

This shortage is causing local salaries to surge and pushing firms to seek workers abroad, a report by Start-Up Nation Central and the Israel Innovation Authority showed last year. And competition for these skilled workers is growing, with startups and multinationals — the likes of Amazon, Google, Facebook and Microsoft — vying for local talent.

In addition, just some 8 percent of the Israeli workforce is in tech, with a large part of the population left out of the boom and traditional industries still struggling with old-fashioned manufacturing processes.

To tackle the shortage in skills, the nation is trying to reach out to demographics sidelined by the tech bonanza — the ultra-Orthodox, the Arab population and women.

Singer, the author, said that one of the solutions was to transform Israel into a “magnet” for foreign talent by making it easier for local startups to employ workers from overseas.

“We need to become more like Silicon Valley and London and New York — those places are very international,” he said. “You go into a startup in those places and you will see people from all over the world. Here you see Israelis, and often from the same army unit. What we need to realize is that we can become a magnet for talent. People would love to come here and join Israeli startups and build their own firms here.”

The dark side of technology

With global tech firms being whipped by a public outcry for invading the privacy of citizens, Israeli firms have not remained unscathed.

Startups like AnyVision and NSO Group have been scrutinized and criticized for the use of their products by authoritarian governments to abuse human rights — highlighting the fact that technology, for all its benefits, can also have a very dark side.

This has spurred human rights and democracy activists to call for regulations that can supervise exports and use of surveillance technologies and those that have the ability to infringe on individuals’ privacy.

So how much of these billions stay in Israel? Shareholders, investors want their pence. What’s the state tax? How many of these start up pioneers are resident Israelis? Does Israel invest in these start-ups with some type of tax allowance?