Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPBetween 25 and 35 million Kurds inhabit a mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia. They make up the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but they have never obtained a permanent nation state.

Where do they come from?

The Kurds are one of the indigenous peoples of the Mesopotamian plains and the highlands in what are now south-eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria, northern Iraq, north-western Iran and south-western Armenia.

Today, they form a distinctive community, united through race, culture and language, even though they have no standard dialect. They also adhere to a number of different religions and creeds, although the majority are Sunni Muslims.

Kurdistan: A State of Uncertainty

Why don’t they have a state?

Image copyrightREUTERS-Image captionDespite their long history, the Kurds have never achieved a permanent nation state

Image copyrightREUTERS-Image captionDespite their long history, the Kurds have never achieved a permanent nation stateIn the early 20th Century, many Kurds began to consider the creation of a homeland – generally referred to as “Kurdistan”. After World War One and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the victorious Western allies made provision for a Kurdish state in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres.

Such hopes were dashed three years later, however, when the Treaty of Lausanne, which set the boundaries of modern Turkey, made no provision for a Kurdish state and left Kurds with minority status in their respective countries. Over the next 80 years, any move by Kurds to set up an independent state was brutally quashed.

Aiming to change the outcome of World War One

Why were Kurds at the forefront of the fight against IS?

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn mid-2013, the jihadist group Islamic State (IS) turned its sights on three Kurdish enclaves that bordered territory under its control in northern Syria. It launched repeated attacks that until mid-2014 were repelled by the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – the armed wing of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD).

An IS advance in northern Iraq in June 2014 also drew that country’s Kurds into the conflict. The government of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan Region sent its Peshmerga forces to areas abandoned by the Iraqi army.

In August 2014, the jihadists launched a surprise offensive and the Peshmerga withdrew from several areas. A number of towns inhabited by religious minorities fell, notably Sinjar, where IS militants killed or captured thousands of Yazidis.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn response, a US-led multinational coalition launched air strikes in northern Iraq and sent military advisers to help the Peshmerga. The YPG and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has fought for Kurdish autonomy in Turkey for three decades and has bases in Iraq, also came to their aid.

In September 2014, IS launched an assault on the enclave around the northern Syrian Kurdish town of Kobane, forcing tens of thousands of people to flee across the nearby Turkish border. Despite the proximity of the fighting, Turkey refused to attack IS positions or allow Turkish Kurds to cross to defend it.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn January 2015, after a battle that left at least 1,600 people dead, Kurdish forces regained control of Kobane.

The Kurds – fighting alongside several local Arab militias under the banner of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) alliance, and helped by US-led coalition air strikes, weapons and advisers – then steadily drove IS out of tens of thousands of square kilometres of territory in north-eastern Syria and established control over a large stretch of the border with Turkey.

In October 2017, SDF fighters captured the de facto IS capital of Raqqa and then advanced south-eastwards into the neighbouring province of Deir al-Zour – the jihadists’ last major foothold in Syria.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPThe last pocket of territory held by IS in Syria – around the village of Baghouz – fell to the SDF in March 2019. The SDF hailed the “total elimination” of the IS “caliphate”, but it warned that jihadist sleeper cells remained “a great threat”.

The SDF was also left to deal with the thousands of suspected IS militants captured during the last two years of the battle, as well as tens of thousands of displaced women and children associated with IS fighters. The US called for the repatriation of foreign nationals among them, but most of their home countries refused.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn October 2019, US troops pulled back from the border with Turkey after the country’s president said it was about to launch an operation to set up a 32km (20-mile) deep “safe zone” clear of YPG fighters and resettle up to 2 million Syrian refugees there. The SDF said it had been “stabbed in the back” by the US and warned that the offensive might reverse the defeat of IS, the fight against which it said it could no longer prioritise.

Turkish troops and allied Syrian rebels made steady gains in the first few days of the operation. In response, the SDF turned to the Syrian government for help and reached a deal for the Syrian army to deploy along the border.

The Syrian government has vowed to take back control of all of Syria.

What has Kobane battle taught us?

Raqqa: The city fit for no-one

Why does Turkey see Kurds as a threat?

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPThere is deep-seated hostility between the Turkish state and the country’s Kurds, who constitute 15% to 20% of the population.

Kurds received harsh treatment at the hands of the Turkish authorities for generations. In response to uprisings in the 1920s and 1930s, many Kurds were resettled, Kurdish names and costumes were banned, the use of the Kurdish language was restricted, and even the existence of a Kurdish ethnic identity was denied, with people designated “Mountain Turks”.

In 1978, Abdullah Ocalan established the PKK, which called for an independent state within Turkey. Six years later, the group began an armed struggle. Since then, more than 40,000 people have been killed and hundreds of thousands displaced.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn the 1990s the PKK rolled back on its demand for independence, calling instead for greater cultural and political autonomy, but continued to fight. In 2013, a ceasefire was agreed after secret talks were held.

The ceasefire collapsed in July 2015, after a suicide bombing blamed on IS killed 33 young activists in the mainly Kurdish town of Suruc, near the Syrian border. The PKK accused the authorities of complicity and attacked Turkish soldiers and police. The Turkish government subsequently launched what it called a “synchronised war on terror” against the PKK and IS.

Since then, several thousand people – including hundreds of civilians – have been killed in clashes in south-eastern Turkey.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPTurkey has maintained a military presence in northern Syria since August 2016, when it sent troops and tanks over the border to support a Syrian rebel offensive against IS. Those forces captured the key border town of Jarablus, preventing the YPG-led SDF from seizing the territory itself and linking up with the Kurdish enclave of Afrin to the west.

In 2018, Turkish troops and allied Syrian rebels launched an operation to expel YPG fighters from Afrin. Dozens of civilians were killed and tens of thousands displaced.

Turkey’s government says the YPG and the PYD are extensions of the PKK, share its goal of secession through armed struggle, and are terrorist organisations that must be eliminated.

Turkey’s fear of a reignited Kurdish flame

What do Syria’s Kurds want?

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPKurds make up between 7% and 10% of Syria’s population. Before the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad began in 2011 most lived in the cities of Damascus and Aleppo, and in three, non-contiguous areas around Kobane, Afrin, and the north-eastern city of Qamishli.

Syria’s Kurds have long been suppressed and denied basic rights. Some 300,000 have been denied citizenship since the 1960s, and Kurdish land has been confiscated and redistributed to Arabs in an attempt to “Arabize” Kurdish regions.

When the uprising evolved into a civil war, the main Kurdish parties publicly avoided taking sides. In mid-2012, government forces withdrew to concentrate on fighting the rebels elsewhere, and Kurdish groups took control in their wake.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn January 2014, Kurdish parties – including the dominant Democratic Union Party (PYD) – declared the creation of “autonomous administrations” in the three “cantons” of Afrin, Kobane and Jazira.

In March 2016, they announced the establishment of a “federal system” that included mainly Arab and Turkmen areas captured from IS.

The declaration was rejected by the Syrian government, the Syrian opposition, Turkey and the US.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPThe PYD says it is not seeking independence, but insists that any political settlement to end the conflict in Syria must include legal guarantees for Kurdish rights and recognition of Kurdish autonomy.

President Assad has vowed to retake “every inch” of Syrian territory, whether by negotiations or military force. His government has also rejected Kurdish demands for autonomy, saying that “nobody in Syria accepts talk about independent entities or federalism”.

Will Iraq’s Kurds gain independence?

Image copyrightHULTON ARCHIVE

Image copyrightHULTON ARCHIVEKurds make up an estimated 15% to 20% of Iraq’s population. They have historically enjoyed more national rights than Kurds living in neighbouring states, but also faced brutal repression.

In 1946, Mustafa Barzani formed the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) to fight for autonomy in Iraq. But it was not until 1961 that he launched a full armed struggle.

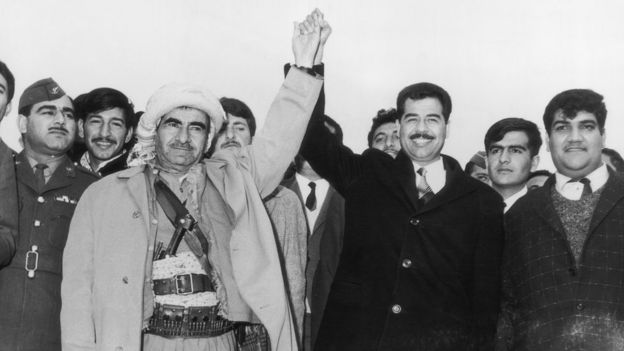

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn the late 1970s, the government began settling Arabs in areas with Kurdish majorities, particularly around the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, and forcibly relocating Kurds.

The policy was accelerated in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq War, in which the Kurds backed the Islamic republic. In 1988, Saddam Hussein unleashed a campaign of vengeance on the Kurds that included the chemical attack on Halabja.

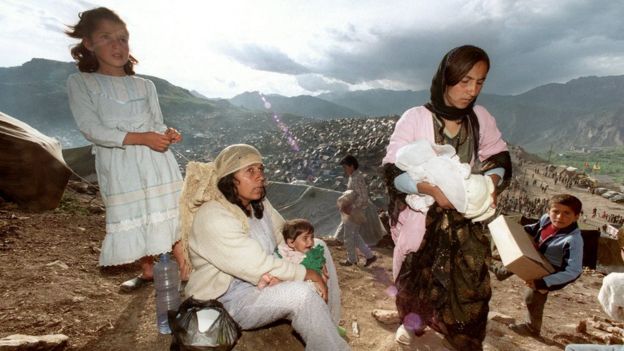

When Iraq was defeated in the 1991 Gulf War, Barzani’s son Massoud and Jalal Talabani of the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led a Kurdish rebellion. Its violent suppression prompted the US and its allies to impose a no-fly zone in the north that allowed Kurds to enjoy self-rule. The KDP and PUK agreed to share power, but tensions rose and a four-year war erupted between them in 1994.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPThe parties co-operated with the US-led invasion in 2003 that toppled Saddam and governed in coalition in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), created two years later to administer Dohuk, Irbil and Sulaimaniya provinces.

Massoud Barzani was appointed the region’s president, while Jalal Talabani became Iraq’s first non-Arab head of state.

In September 2017, a referendum on independence was held in both the Kurdistan Region and the disputed areas seized by the Peshmerga in 2014, including Kirkuk. The vote was opposed by the Iraqi central government, which insisted it was illegal.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESMore than 90% of the 3.3 million people who voted supported secession. KRG officials said the result gave them a mandate to start negotiations with Baghdad, but then Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi demanded that it be annulled.

The following month Iraqi pro-government forces retook the disputed territory held by the Kurds. The loss of Kirkuk and its oil revenue was a major blow to Kurdish aspirations for their own state.

After his gamble backfired, Mr Barzani stepped down as the Kurdistan Region’s president. But disagreements between the main parties meant the post remained vacant until June 2019, when he was succeeded by his nephew Nechirvan.

Iraqi Kurdistan: State-in-the-making?

What a mess. At first I thought PREZ had blundered but now I wonder if it is not best to let the mumsers fight each other forever.